- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Transparency and Collaboration Key to the Success of Value-Based Payment Models

As the task of describing value delivery in cancer care seems to grow in complexity the closer that we examine it, this is essential in order to both rationally control the growth of healthcare costs and ensure that we do not undermine patient care.

Despite attempts by government, healthcare systems, and payers to rein in costs, healthcare expenditures in the United States continue to grow at a significant rate. In 2015, total US healthcare spending rose to $3.2 trillion, or a cost of nearly $10,000 per person.1 Despite attempts, legislated through the Affordable Care Act, to reduce this growth, healthcare—related inflation actually increased from 4.6% in 2014 to 5.8% in 2015—a rate that is nearly 5-times that of inflation for the American economy overall.2

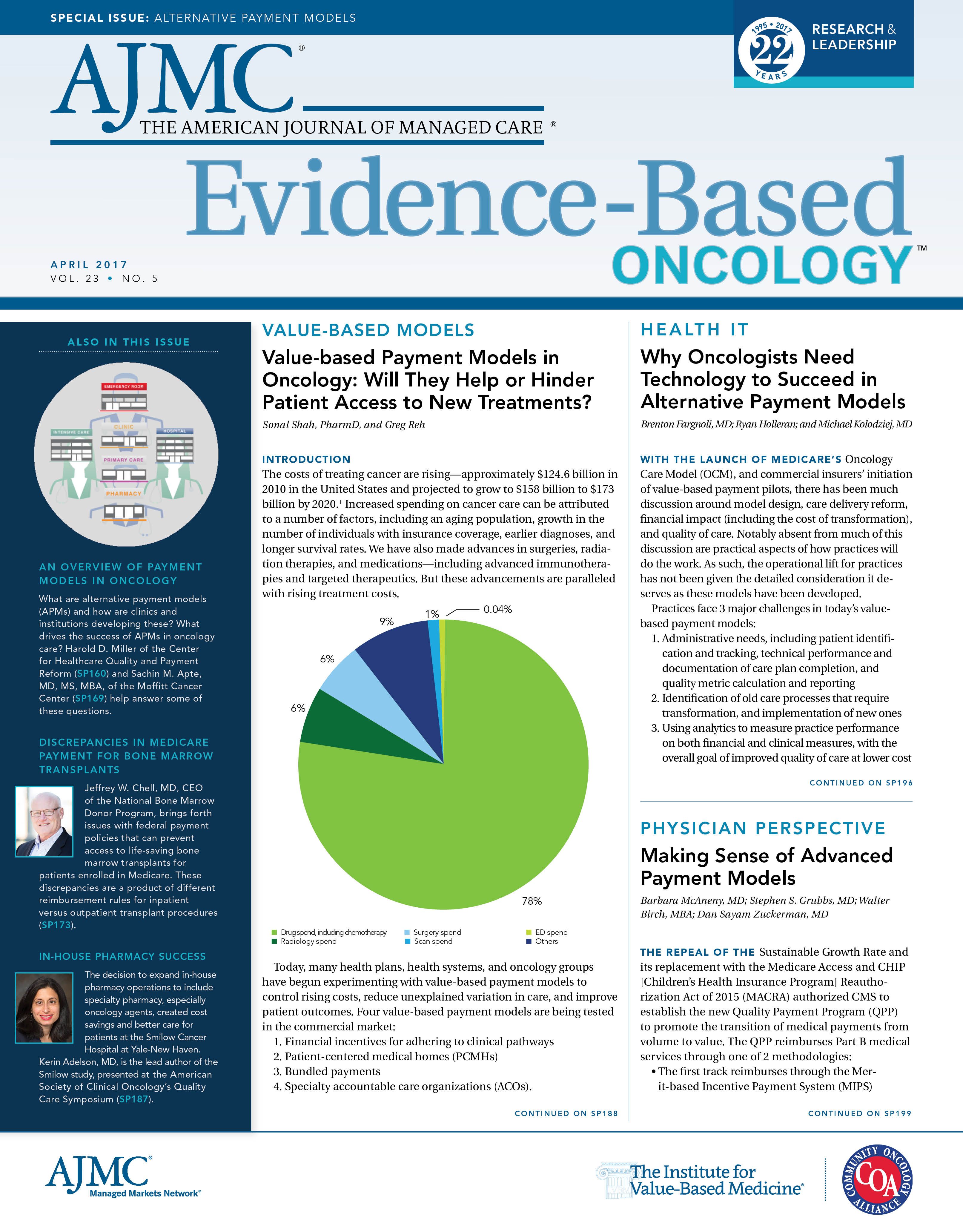

In addition to this increase in aggregate costs, pharmaceutical costs grew by 9% and out-of-pocket health-related spending rose by 2.6%.1 This astronomical (and growing) level of spending, begs the question, “What kind of healthcare are we getting for over $3 billion?” Our inability to answer this question easily, consistently, and transparently across different healthcare systems and payer networks reflects how difficult it is to assess value in healthcare delivery.

Value has become a catchword in healthcare, and this has been true for a while already within the domain of cancer care, where the extraordinary complexity and intensity of effective care, coupled with the astronomical prices of new anticancer agents, have led many to question the economic sustainability of delivering effective and innovative care to this population of patients. Everyone, from payers to employers to professional societies (such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology) and consortia of experts (such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network), has tried to tackle the protean tasks of describing and assessing value in cancer care. None of these major stakeholders has been particularly successful in developing a robust compelling system for assessing the value of care delivery for an individual patient or even for a diagnostically similar population of patients.

Although value is traditionally defined as cost/outcomes, it does a poor job of integrating clinical and diagnostic risks (including molecular, genomic, and proteomic data) into this value assessment. A further limitation is that the nebulous nature of cancer-related outcomes and the profound difficulty of capturing survival outcomes further undermine the degree to which value in cancer care can be reliably assessed. If overall value in healthcare is to be enhanced over time and costs controlled in a meaningful way that does not undermine the quality of cancer care for individual patients, there will need to be an unprecedented degree of transparency and collaboration among key stakeholders.

This issue of Evidence-Based Oncology™ attempts to describe how this can be accomplished through advances in data analytics, innovative payment models, addressing the rising costs of pharmaceuticals rationally, and ensuring that these efforts are supported through insightful public policy making. Sonal Shah, PharmD, and Greg Reh from Deloitte review value-based payment models from a multi-faceted stakeholder perspective. The team from Flatiron Health describes the importance of technology and data transparency in meeting the requirements of innovative payment models. Harold Miller discusses some of the alternative payment model opportunities for physicians that may allow for the development of more effective at-risk models for healthcare payment. S. Mantravadi, PhD, MS, MPH, from the University of West Florida, tries to place the rising cost of effective, new pharmaceutical agents in the context of improved patient outcomes.

Inasmuch as the task of describing value delivery in cancer care seems to grow in complexity the closer that we examine it, this is essential in order to both rationally control the growth of healthcare costs and ensure that we do not undermine the care of the patients whom we serve. We will continue to revisit this issue over time and invite you to be part of this ever-evolving conversation.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Joseph Alvarnas, MD, is director, medical Quality and Quality, Risk and Regulatory Management, City of Hope. He is also the editor-in-chief of Evidence-Based Oncology™.

REFERENCES

1. NHE fact sheet. CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/ nhe-fact-sheet.html. Updated March 21, 2017. Accessed March 26, 2017.

2. United States inflation rate. Trading Economic website. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-states/inflation-cpi. Published March 15, 2017. Accessed March 26, 2017.

Insights Into Patient Portal Engagement Leveraging Observational Electronic Health Data

January 12th 2026This analysis of more than 250,000 adults at least 50 years old with chronic conditions showed lower portal use among older, non–English-speaking, and Black patients, underscoring digital health equity gaps.

Read More

Exploring Racial, Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Care Prior Authorization Decisions

October 24th 2024On this episode of Managed Care Cast, we're talking with the author of a study published in the October 2024 issue of The American Journal of Managed Care® that explored prior authorization decisions in cancer care by race and ethnicity for commercially insured patients.

Listen

Subjective and Objective Impacts of Ambulatory AI Scribes

January 8th 2026Although the vast majority of physicians using an artificial intelligence (AI) scribe perceived a reduction in documentation time, those with the most actual time savings had higher relative baseline levels of documentation time.

Read More

Telehealth Intervention by Pharmacists Collaboratively Enhances Hypertension Management and Outcomes

January 7th 2026Patient interaction and enhanced support with clinical pharmacists significantly improved pass rates for a measure of controlling blood pressure compared with usual care.

Read More