- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

How to Create Successful Alternative Payment Models in Oncology

By identifying ways to improve cancer care and then designing alternative payment models (APMs) to overcome current payment barriers, APMs can enable oncology practices to deliver better care to patients and save money for payers in a way that is financially sustainable for the practices.

The term “Alternative Payment Model” (APM) was added to the healthcare lexicon as a result of the passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP [Children’s Health Insurance Program] Reauthorization Act (MACRA) in 2015.1 Although MACRA is best known for repealing the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and creating the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), Congress expressed a preference for APMs rather than MIPS by offering physicians a 5% bonus, higher annual updates, and exemption from MIPS if they participate at a minimum level in certain types of APMs.

What Is an APM?

MACRA defines an APM as “a model under section 1115A, the shared savings program under section 1899, a demonstration under section 1866C, or a demonstration required by Federal law.” Section 1115A is the part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that created the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI).2 It requires testing “payment and service delivery models…where… there is evidence that the model addresses a defined population for which there are deficits in care leading to poor clinical outcomes.” The focus is to create models that are “expected to reduce program costs…while preserving or enhancing the quality of care received…” The law lists 24 models that CMMI is authorized to pursue, such as:

- “Establishing care coordination for chronically ill applicable individuals at high risk of hospitalization through a health information technology—enabled provider network that includes care coordinators, a chronic disease registry, and home telehealth technology,” and

- “Aligning nationally recognized, evidence-based guidelines of cancer care with payment incentives…in the areas of treatment planning and follow-up care planning for… individuals…with cancer.”2

Terms such as “bundle,” “episode,” “global payment,” and “shared savings” do not appear anywhere in Section 1115A. It allows any payment model that will “improve the quality of care without increasing spending,” “reduce spending …without reducing the quality of care,” or “improve the quality of care and reduce spending.”

Section 1899, which authorized the Medicare Shared Savings Program, states that its purpose is to create a program that “promotes accountability for a patient population and coordinates items and services under parts A and B, and encourages investment in infrastructure and redesigned care processes for high quality and efficient service delivery.”3 Most people are not aware that this section authorizes use of partial capitation and “other payment models” as well as shared savings, because CMS has not implemented these other approaches.

The law clearly indicates that the core element of a “model” is a method of improving care delivery, not simply a different method of payment.2 It’s called an “alternative” payment model because a) it must demonstrate it will not increase Medicare spending, and b) savings in Medicare Parts A or D can be counted, not just savings in Medicare Part B or physician fee-schedule services. The current requirement that new physician service payments must be accompanied by reduced payments for other physician services does not apply to APMs.

Why Would Physicians Want to Be Part of an APM?

Two important misperceptions about APMs are: 1) they are needed so physicians will have “incentives” to deliver care differently and 2) the only reason physicians would want to be in an APM is to be exempt from MIPS or to receive the bonuses Congress authorized. The reality is that many physicians want to deliver care in different and better ways, but cannot do so due to barriers in the current payment system. Two major barriers4 are:

Lack of payment or inadequate payment for high-value services. Medicare and most health plans do not pay physicians for many services that would benefit patients and reduce spending, such as responding to patient phone calls or using nurses to help patients manage their health problems.

Financial penalties for delivering a lower-cost mix of services.

Under fee-for-service (FFS) payment, physician practices that perform fewer or lower-cost procedures may no longer receive enough revenue to cover their practice costs. Today, physician practices are paid less when they help patients stay healthy enough to require fewer services.

A well-designed APM can overcome these barriers by paying adequately for high-value services and basing payment on the conditions or symptoms being managed and the outcomes achieved, rather than on the specific treatments used.

Another misperception is that physicians and other providers must accept significant financial risk for Medicare spending as part of an APM. Many physicians have been unable or unwilling to participate in existing APMs because of the high level of financial risk involved. However, sections 1115A and 1899 do not require that APMs impose financial risk on physicians. One of the only 2 models developed under Section 1115A that has been certified by the CMS Actuary for national expansion is the Diabetes Prevention Program, and there is no financial risk for providers in that model.5

What MACRA requires is that some entity accept “more than nominal financial risk” under an APM in order for a physician to receive a 5% bonus, higher annual update, and MIPS exemption. CMS was widely criticized for setting the “more than nominal” standard too high in its proposed regulations, and a more reasonable standard was included in the final rule. This will make it easier for physicians to participate in APMs that qualify for bonuses and the MIPS exemption. However, there can still be significant advantages to APMs that do not meet the risk requirements.

How APMs Could Help Improve Cancer Care

Rather than choosing payment models and forcing physicians to deliver care that fits the payments, MACRA and the ACA clearly wanted the process to start with changes in care delivery and have payment models designed to support those changes. There are many opportunities to improve cancer care that are not being addressed due to barriers in FFS payment, and well-designed APMs could help change this. Three such opportunities are:

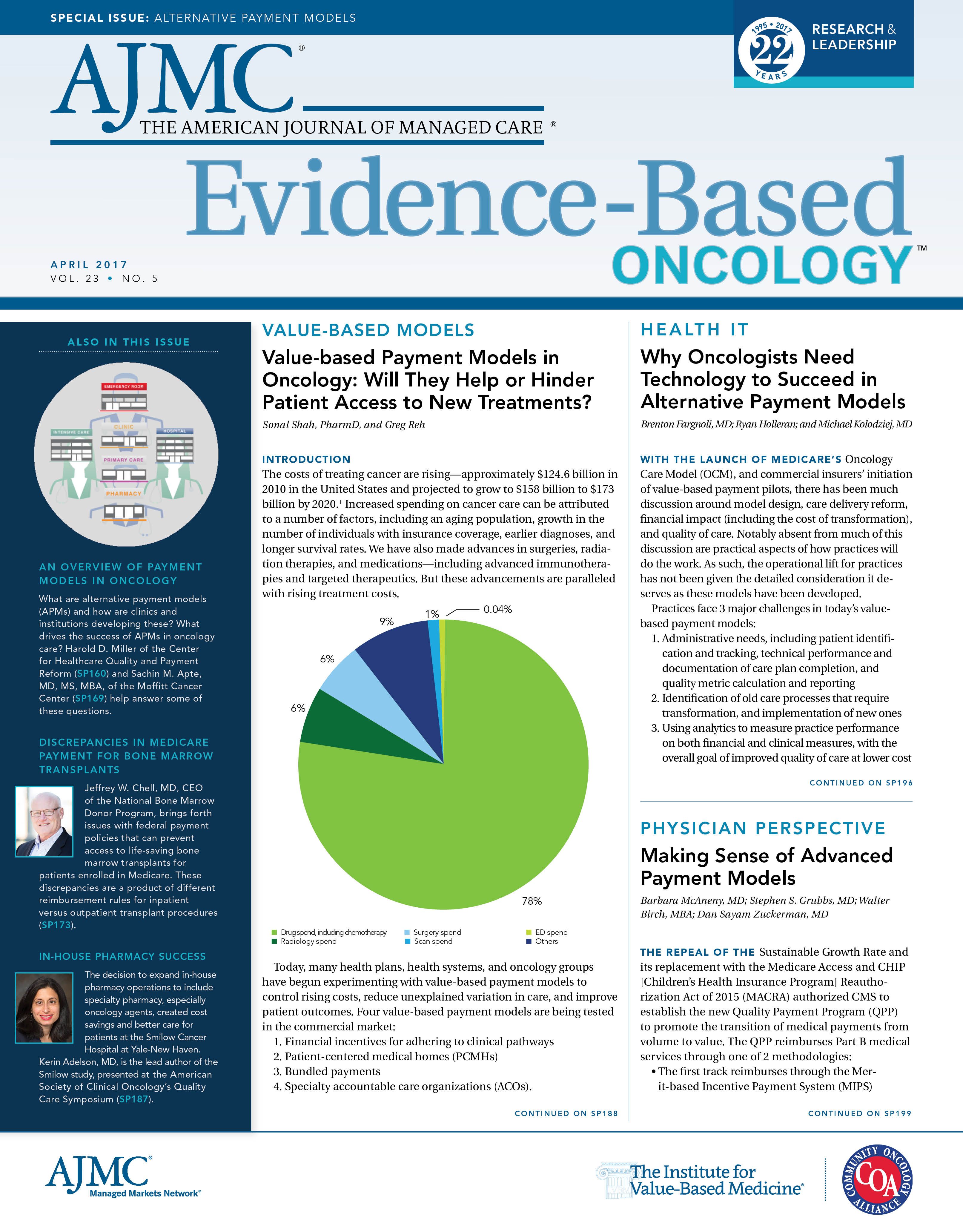

1. Reducing hospital visits due to complications of chemotherapy. The benefits of chemotherapy are often accompanied by side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, and neutropenia, that can lead to serious complications, such as, dehydration and infection. Many patients receiving chemotherapy go to emergency departments (EDs) for treatment of these complications, and they are often admitted to the hospital because of the severity of the complications.

Chemotherapy-related ED visits and hospitalizations represent a significant portion of overall spending on cancer care. A 2010 study estimated that commercial insurance plans spent more than $9000 per patient on chemotherapy-related ED visits and hospital admissions,6 and a 2012 study of Medicare beneficiaries receiving cancer treatment found that risk-adjusted per-patient spending on hospitalizations varied by more than $3000 across the country.7

Two projects supported by CMMI grant funding have shown that significant reductions in ED visits and admissions can be achieved by redesigning the way care is delivered to patients receiving chemotherapy:

• The Patient Care Connect Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Health System Cancer Community Network employed nonclinical patient navigators to screen for distress and encourage patients to seek early help from the oncology practice, rather than delay care or use the ED for non—life-threatening conditions.8 The project significantly reduced ED visits and hospitalizations and achieved savings 10 times as great as the cost of the navigators.9

• In the Community Oncology Medical Home (COME HOME) project, an improved triage system and enhanced access to outpatient treatment enabled early, rapid, low-cost interventions, such as intravenous hydration when patients experienced chemotherapy-related complications. An independent evaluation showed significant reductions in ED visits, hospitalizations, and total cost of care for the patients.10

Most oncology practices can’t implement these successful approaches for a simple reason: they can’t afford to. Federal grants were needed to enable the UAB and COME HOME practices to implement these initiatives.

How could an APM enable these programs to continue after the grants end and allow other practices to replicate them? The simplest approach would be to make additional payments to cover the costs of the currently unbillable services in return for accountability by the oncology practice to achieve low rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for its patients. The 2 components of the APM would be:

Flexible monthly payments to support enhanced services.

• A flexible payment could be used to employ patient navigators or triage nurses or to cover financial losses from keeping treatment slots open on the practice schedule. Since the payments are intended to avoid complications as well as to enable early treatment when complications arise, it is more appropriate to base the payment on the patient, rather than base the payment on the delivery of a specific service to that patient. A growing number of APMs make “per member per month” payments to physician practices so revenues aren’t driven by the volume of services delivered.

Adjustments to the payments based on performance in achieving outcomes.

• Since the purpose of the additional payments is to help avoid ED visits and hospital admissions, the risk-adjusted rate of visits and admissions for a practice would be measured, and if those rate(s) are higher than rates other practices had achieved with similar resources, the amount of the per-patient payment would be reduced.

This 2-part structure is different and better than most “value-based payment” models being used today:

• In MIPS and other pay-for-performance systems, the oncology practice receives no additional resources to deliver additional and better services, merely a small change in current FFS payments as an “incentive” to do something they can’t afford.

• In shared savings models, the practice receives no up front resources to support different services. If it is already successful in controlling ED use, it won’t qualify for the shared savings payments it may need to sustain the services that achieve that result.

Improving end-of-life care.

2. There is widespread concern about the number of cancer patients who receive treatments that will neither cure their disease nor prolong their lives, but will significantly diminish quality of life during their final months. These prolonged treatments can lead to poor end-of-life experiences for patients and families alike, as well as to very high expenses for payers.

Multiple studies have shown that palliative care services can significantly reduce ED visits, hospitalizations, and other avoidable services and the savings can more than offset the cost of the services.11 However, once again, oncology practices don’t offer palliative care services because they can’t afford to. Medicare and most health plans will only pay for multidisciplinary in-home palliative care under a hospice benefit, and many patients and physicians aren’t willing to completely terminate treatment and declare that the patient has only 6 months to live in order to qualify.

An APM could fill this gap. Once again, 1) a monthly payment could provide the resources an oncology practice or palliative care team need to provide good care and 2) a performance-based adjustment, based on rates of avoidable ED visits, hospitalizations, and procedures, would provide the accountability payers need to assure that overall spending will not increase. Instead of arbitrary eligibility criteria to limit spending, the monthly payment could be stratified based on patient needs, so the resources the oncology practice (or its palliative care team partner) receive are matched to the opportunities to improve care.

Most of the “episode” payment models being used today are triggered by delivery of a particular procedure, and they financially penalize a physician for not delivering that procedure when it is not needed. A better approach is a “condition-based payment” that bases payment on the patient’s needs, not on how many or what types of services were delivered.12

Controlling drug spending.

3. For most types of cancer, pharmaceuticals are a major component of overall spending on cancer treatment. Although high prices are a major reason for high drug spending, there are opportunities beyond price reductions to reduce drug spending.

For example, one of the biggest sources of Medicare drug spending in cancer care in recent years wasn’t a chemotherapy drug, it was pegfilgrastim, which is used to stimulate production of white blood cells to reduce the chance of infection resulting from chemotherapy. Medicare spent more than $1.2 billion on pegfilgrastim injections in 2015, the third highest amount of spending on any Part B medication.13 The drug is very expensive, averaging more than $13,000 per patient in 2015.

Although white-cell stimulating factors (CSFs) such as pegfilgrastim can help prevent serious infections when patients receive highly toxic chemotherapy, the drugs can also produce severe bone pain and other side effects. The American Society of Clinical Oncology issued a Choosing Wisely guideline recommending use of CSFs for primary prevention of febrile neutropenia only for chemotherapy regimens with a 20% or higher risk of the complication.14

Two recent studies, in different parts of the country and for Medicare and commercially insured patients, found only 70% adherence to the Choosing Wisely guideline.15,16 If 30% of the patients getting the drug don’t really need it, that could represent $400 million in savings for the Medicare program—the same amount that would be saved if the price of every Part B drug was 2% lower.

An APM could help achieve these savings while protecting patients. The Choosing Wisely recommendation is a guideline, not an absolute rule. Flexibility is needed to address individual patient needs, and if a patient doesn’t receive a CSF, the oncology practice needs effective systems to monitor the patient and respond to problems quickly—the kinds of services described earlier that are not compensated under current FFS payments. Moreover, maintaining the guideline over time requires tracking 1) use of the CSF, 2) complication rates associated with new chemotherapy regimens, and 3) the effectiveness of new CSFs that enter the market. Since these are all costs that are not paid for today, the APM could 1) pay a per-patient amount that the practice could use to cover these costs in return for 2) the practice documenting adherence to the guideline and the reasons for deviations.17

What About the Oncology Care Model?

In 2016, CMMI contracted with 190 oncology practices to implement an APM called the Oncology Care Model (OCM). OCM has a 2-part payment structure similar to what is described above: a monthly payment for each patient receiving chemotherapy and a performance-based payment.18 However, the details of the design create concerns for both oncology practices and patients:

• The performance-based payment is based on whether total spending on the patient is higher or lower than a CMS-defined target. This places the practice at risk not just for ED visits and hospitalizations, but also for things beyond its control, such as treatments for health problems other than cancer, increases in drug prices, etc.19

• The target spending level is not adjusted based on how many patients are receiving highly toxic regimens, nor are there quality measures to ensure that patients receive CSFs when appropriate. This means that practices could receive financial rewards for failing to administer expensive drugs, such as pegfilgrastim, to patients who need them.

• Monthly payments are only for patients receiving chemotherapy, making it impossible to pay for palliative care after treatment ends. Moreover, the higher payment creates a perverse incentive to continue using chemotherapy.

In contrast, the CMMI Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) payment model has flexible monthly payments andadjustments based on performance without creating similar problems.20 Primary care practices receive per-beneficiary-per-month and performance-based payments, but the practice receives the performance-based payment in advance. Payments are reduced only if the rates of ED visits or hospitalizations are high; reductions are not based on total spending. CMS has certified that the CPC+ APM would meet the “more than nominal financial risk” standards under MACRA, so primary care physicians in that model would qualify for the 5% bonus, higher updates, and exemption from MIPS.

Creating Physician-Focused APMs

Clearly, well-designed APMs can help oncology practices deliver better care to patients and save money for payers in a way that is financially sustainable for the practices. In contrast, poorly designed APMs that simply shift financial risk to oncologists for events they cannot control, or that fail to provide the resources needed to deliver better care, could cause serious harm for patients.

There is no ideal APM design. Some practices, particularly small ones, may only be able to tackle 1 change at a time, and more narrowly focused APMs will work better for them. Other practices may prefer broader condition-based APMs in order to make more improvements simultaneously.

â—†

Congress indicated it wants physicians, not payers, to take the lead in designing APMs by creating a special process for encouraging the development and implementation of “physician-focused payment models.”21 Now, cancer care providers who develop better ways of delivering care can also design solutions to the payment barriers that prevent implementation of those changes and submit their proposals to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for consideration.22 This creates a much-needed opportunity to accelerate the development and implementation of value-based payment systems that will benefit patients, payers, and providers.

Harold D. Miller is president and chief executive officer, Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE

Harold D. Miller

President and CEO

Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform

320 Fort Duquesne Blvd, Suite 20-J Pittsburgh, PA 15222

Email: Miller.Harold@CHQPR.org

REFERENCES

1. Public Law 114—10. US Congress website. https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ10/PLAW114publ10.pdf. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed February 11, 2017.

2. 42 U.S.C. 1315A — Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. US Government Publishing Office website.

https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/search/pagedetails.action;jsessionid=89VnQwRD4yB97CpfrkKLpVyvmvJsWR5STjK5RHlJdnvwQ6cyWxTL!888557223!1765804297?st=Center+for+Innovation+Management&granuleId=USCODE-2010-title42-chap7-subchapXI-partA-sec1315a&packageId=USCODE-2010-title42. Published 2010. Accessed February 11, 2017.

3. 42 U.S.C. 1395JJJ — Shared Savings Program. US Government Publishing Office website. https:// www.gpo.gov/fdsys/search/pagedetails.action?collectionCode=USCODE&browsePath=Title+42%2FChapter+7%2FSubchapter+Xviii%2FPart+E%2FSec.+1395jjj&granuleId=USCODE-2011-title42-chap7-subchapXVIII-partE-sec1395jjj&packageId=USCODE-2011-title42&collapse=true&fromBrowse=true. Published 2011. Accessed February 11, 2017.

4. Miller HD. The building blocks of successful payment reform: designing payment systems that support higher-value health care. Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform website. http:// www.chqpr.org/downloads/BuildingBlocksofSuccessfulPaymentReform.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 11, 2017.

5. Spitalnic P. Certification of Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program. CMS website. https://www.cms. gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/Downloads/Diabetes-Prevention-Certification-2016-03-14.pdf. Published March 14, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2017.

6. Fitch K, Pelizzari PM, Pyenson B. Cost drivers of cancer care: a retrospective analysis of Medicare and commercially insured population claim data 2004-2014. Milliman website. http://www.milliman. com/uploadedFiles/insight/2016/trends-in-cancer-care.pdf. Published April 2016. Accessed February 11, 2017.

7. Clough JD, Patel K, Riley GF, Rajkumar R, Conway PH, Bach PB. Wide variation in payments for Medicare beneficiary oncology services suggests room for practice-level improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(4):601-608. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0964.

8. Rocque GB, Partridge EE, Pisu M, et al. The Patient Care Connect Program: transforming health care through lay navigation. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(6):e633-e642. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.008896.

9. Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al; Patient Care Connect Group. Resource use and Medicare costs during lay navigation for geriatric patients with cancer [published online January 26, 2017]. JAMA Oncol. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307.

10. NORC at the University of Chicago. HCIA disease-specific evaluation: second annual report. CMS website. https://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/hcia-diseasespecific-secondevalrpt.pdf. Revised March 2016. Accessed February 11, 2017.

11. Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, Normand C. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2014; 28(2):130-150. doi: 10.1177/0269216313493466.

12. Miller HD, Marks SS; American Medical Association; Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform (CHQPR). A guide to physician-focused payment models. CHQPR website. http://www. chqpr.org/downloads/Physician-FocusedAlternativePaymentModels.pdf. Published November 2015. Accessed February 3, 2017.

13. Author’s analysis of 2015 Medicare Part B spending data. See: 2015 Medicare drug spending data. CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/2015MedicareData.html. Published December 6, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2017.

14. Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: the top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1715-1724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8375.

15. Ramsey SD, Fedorenko C, Chauhan R, et al. Baseline estimates of adherence to American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Board of Internal Medicine Choosing Wisely initiative among patients with cancer enrolled with a large regional commercial health insurer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(4):338343. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002717.

16. Rocque GB, Williams CP, Jackson BE, et al. Choosing Wisely: opportunities for improving value in cancer care delivery? J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(1):e11-e21. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.015396.

17. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Patient-centered oncology payment: payment reform to support higher quality, more affordable cancer care. ASCO website. http://www.asco.org/sites/ new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/advocacy-and-policy/documents/asco-patient-centered-oncology-payment.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 3, 2017.

18. RTI International, Actuarial Research Corporation. Oncology care model: OCM performance-based payment methodology, version 1.1. CMS Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation website. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/ocm-methodology.pdf. Published June 27, 2016. Accessed February 3, 2017.

19. Polite BN, Miller HD. Medicare innovation center oncology care model: a toe in the water when a plunge is needed. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):117-119. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002899.

20. Comprehensive Primary Care Plus: CPC+ payment methodologies: beneficiary attribution, care management fee, performance-based incentive payment, and payment under the Medicare physician fee schedule. CMS Center for Medicare & Medicaid website. https://innovation.cms.gov/ Files/x/cpcplus-methodology.pdf. Published January 1, 2017. Accessed February 3, 2017.

21. 42 USC 1395ee (c): Practicing Physicians Advisory Council; Council for Technology and Innovation. US House of Representatives Office of the Law Revision Counsel website. http://uscode. house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title42-section1395ee&num=0&edition=prelim. Updated April 16, 2015. Accessed February 20, 2017.

22. PTAC: Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/ptac-physician-focused-payment-model-technical-advisory-committee. Updated December 5, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2017.