- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

An Oncologist's Perspective: Preparation for New Payment Models in Cancer Care

A dive into the Quality Payment Program and other healthcare reform models introduced in cancer care that healthcare providers are adjusting to as we move toward value-based care.

Introduction

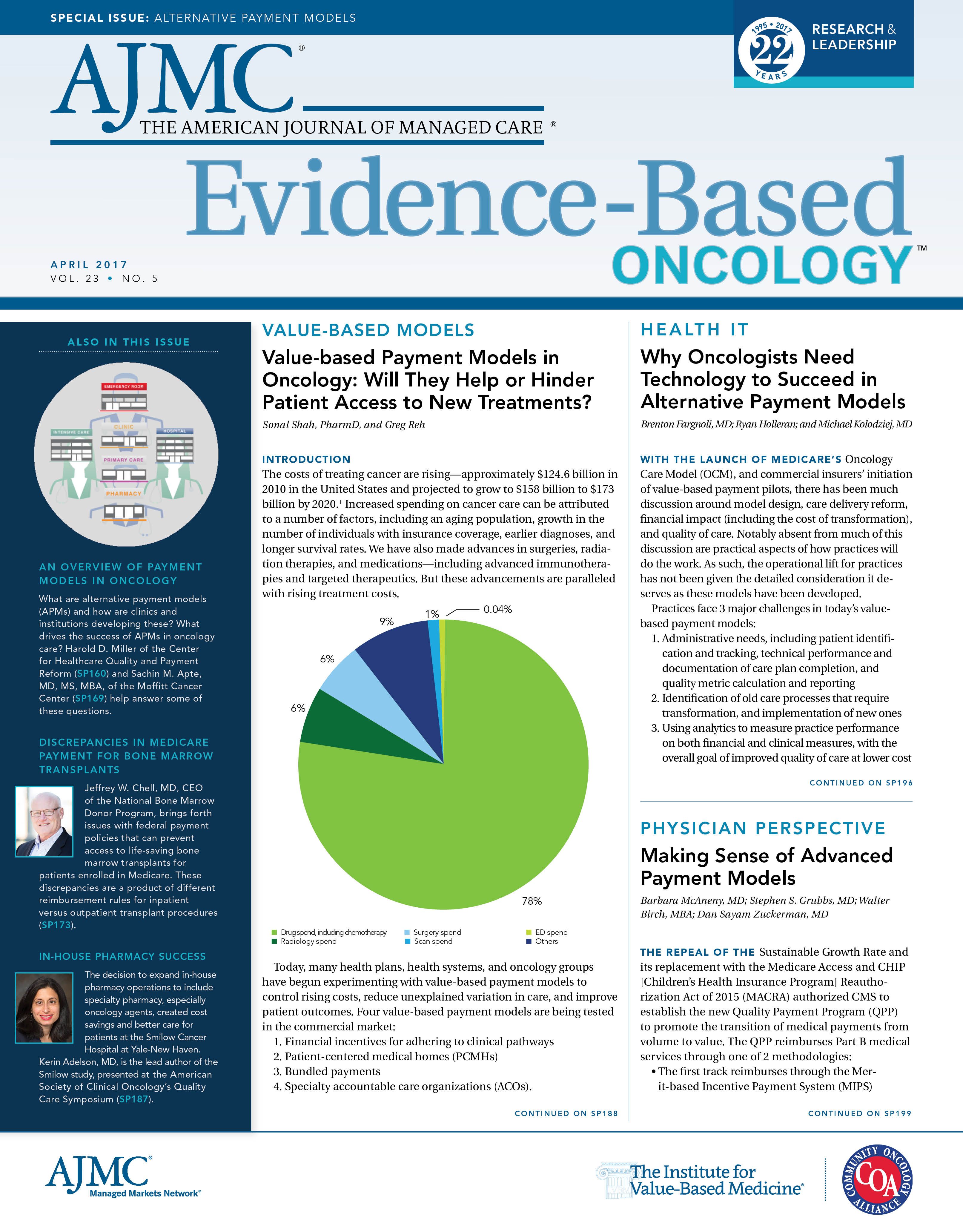

In 2013, the Institute of Medicine (IOM; now called The National Academy of Medicine) described a cancer care delivery system in crisis.1 The stress on our healthcare system is amplified by an aging population, healthcare workforce shortage, and rising costs. By 2020, the cost of cancer care is estimated to be $173 billion, a staggering 39% increase over 2010 levels. In a 2001 report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, the IOM described 6 aims for healthcare: safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.2 Components of the 13 IOM recommendations directly address issues such as providing high-quality, evidence-based care; sharing health information; improving processes of care; using resources efficiently; coordinating care; and redesigning payment methods to incentivize quality enhancement and remove barriers that impede quality improvement.2 In the 16 years since the publication of Crossing the Quality Chasm, several key issues have remained unresolved and barriers to improving quality and value in oncology have persisted. The Quality Payment Program (QPP) by CMS aims to drive further transformation forward in oncology.

The care for a patient afflicted with cancer is complex, resource-intense, and constantly evolving. These challenges are compounded by the changes underway in physician payment reform. It is critical that oncologists and leaders of hospitals and healthcare systems comprehend these changes to successfully adapt and remain agile while providing high-quality, compassionate, and timely care to patients with cancer. In parallel with the QPP, cancer care providers need to develop comprehensive, individualized, and forward-thinking strategies to successfully adapt to new payment models in oncology. Such strategies may necessitate workflow changes that must be tracked.

Quality Payment Program

Strong bipartisan support for the Medicare Access and CHIP [Children’s Health Insurance Program] Reauthorization Act (MACRA) in 2015 led to the final rule being published in October 2016. MACRA, rebranded as QPP, includes 2 tracks:

• The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)

• Advanced alternative payment models (APMs)

• MIPS, which includes Medicare Part B payments and excludes Part A (hospital payment), combines portions of existing programs into a single composite score. The legacy programs include the Physician Quality Reporting System, “Meaningful Use,” and the Value-based Payment Modifier. For 2017, the score for the 4 MIPS categories will be weighted as follows:

• Improvement activities (IAs), 15%

• Advancing care information (ACI), 25%

• Quality, 60%

• Cost, 0%

It is important to note that the weighting will change over time: by 2019, both quality and cost will be weighted at 30%. CMS’ QPP interactive website contains tools and information for providers and hospitals.3 For 2017, providers may choose not to participate, but will receive a 4% payment reduction. Submission of at least 1 quality or IA metric, or the required ACI metrics, will avoid any penalties. The provider may choose to submit data for 90 consecutive days or an entire year. Submitting all MIPS data for at least 90 days may result in up to a 4% increase plus a performance bonus. For the first MIPS payment year in 2019 (performance year 2017), payment adjustments will be at ±4% based on the MIPS composite score, and by 2022, the adjustment will be at ±9%.

Advanced APMs provide incentives to promote high-quality and cost-efficient care for a specific condition, defined episode, or a population. Advanced APMs require use of certified electronic health record (EHR) technology; they tie payment to quality and entail downside financial risk. A subset of advanced APM participants, defined as Qualifying Professionals (QPs), will see a 5% increase in Part B payments from 2019 to 2024, be exempt from MIPS, and will have higher base rates beginning in 2026. In 2019, QPs must meet minimum requirements of defined percentages of Medicare payments and patients (25% and 20%, respectively) coming through the advanced APM. For 2023 and beyond, the payment and patient thresholds increase to 75% and 50%, respectively. Advanced APM participants who do not satisfy the QP requirements may still receive favorable MIPS scores.

Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee

MACRA incentivizes physicians to participate in APMs, including the development of physician-focused payment models (PFPMs). The Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC), created by MACRA, provides recommendations to the HHS secretary on proposals for PFPMs. Ten criteria are used to assess a proposed PFPM, including an emphasis of value over volume, care coordination, defined quality and cost components, and whether the PFPM will expand the existing scope for APMs. The PTAC mechanism may be an opportunity for advanced APM development for subspecialty societies, large community-based multi-specialty groups, and tertiary cancer centers.

Strategic Considerations for QPP Implementation

Although MIPS may appear to represent a rebundling of existing programs, the mounting financial penalties for sub-optimal MIPS composite scores may push providers into an APM over the next several years. The assumption of risk could usher in dramatic changes as providers assess the scale of their operations and place a premium on care coordination and resource management. These changes will force oncologists to develop or acquire the necessary subject matter expertise. At Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, a multi-disciplinary team meets regularly to share information and begin building institutional knowledge, with outside consultation obtained in a targeted manner. This knowledge must be disseminated throughout the practice or organization to facilitate the change management required for QPP implementation. Successful adaption to new payment models will rely heavily on strategy, and subsequent workflow changes can then be designed to deploy strategy. The 6 issues listed below can help inform the organization’s multi-disciplinary team as it starts designing a strategy.

Determine if a cancer care provider qualifies.

1. A provider is part of the QPP if it participates in an advanced APM or bills Medicare

Part B more than $30,000 a year and provides care for more than 100 unique Medicare Part B patients a year.3 MIPS-eligible providers include:

• Physicians

• Physician assistants

• Nurse practitioners

• Clinical nurse specialists

• Certified registered nurse anesthetists.

At Moffitt, these nonphysician mid-level providers are an integral and large part of our care team. Their impact must be accounted for, a difference from prior physician-focused federal programs, such as Meaningful Use.

Determine a 2017 reporting period.

2. Providers have an option to choose their pace for 2017. While reporting began on January 1, 2017, a provider who wants to participate in a limited fashion can begin reporting by October 2, 2017. Providers may opt not to report, submit a minimum amount of data (ie, 1 quality measure), report on 90 days of data, or submit data for an entire year. Data submission is due by March 31, 2018. Although the reporting year is 2017, the payment adjustment is made on January 1, 2019.

Determine if the provider should participate as an individual (National Provider Identifier) or report as a group practice under a single Tax Identification Number.

3. There are pros and cons to individual versus group reporting. Individual reporting allows oncologists to choose the most relevant and meaningful quality metrics so that they can have an impact on the quality component of the MIPS score, in addition to having the potential for greater cost control. Group reporting, on the other hand, lets providers distribute the administrative burden associated with QPP participation. A bigger practice, for instance, may be better positioned to absorb financial penalties resulting from a poor performance.

Decide on MIPS versus advanced APM participation.

4. CMS expects a majority of eligible clinicians to initially enroll in MIPS. Currently, the only oncology-specific advanced APM is the Oncology Care Model (OCM), which focuses on chemotherapy administration. Stakeholders who want to be considered for an advanced APM also have the option to submit an application to PTAC.4

5. Evaluation of reporting mechanisms.

CMS requires that data be submitted using an approved method, depending on the metric. The Quality, ACI, and IA metrics can be reported via a Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR), Qualified Registry, EHR, or Web interface with CMS (for groups of 25 or more). Attestation can be used for ACI and IA.5 For bigger groups, Quality can be reported via Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Potential costs associated with the chosen reporting mechanisms will need to be accounted for. In addition to data submission, some QCDRs may be able to provide modeling to optimize selection of metrics based on historic performance.

Provider employment model.

6.The provider’s model of employment may weigh heavily on the approach to QPP implementation. A self-employed provider or independent single-specialty practice will have inherently different considerations than a hospital-employed provider in a large multispecialty group practice. For example, a smaller-scale practice will have more autonomy in selecting quality metrics and improvement activities that are aligned with the practice. Alternatively, a large-scale practice may incur an administrative burden that is less significant per provider and it will have more ability to accept and absorb downside risk. A large practice may also have greater access to sophisticated analytics and more data to better inform decisions. Regardless of the employment situation for an oncology provider, it is important that the providers communicate effectively with the affiliated hospital, such that efforts are aligned and coordinated. At Moffitt, early efforts are focused on integration of strategy across the enterprise to account for downstream impacts of actions on both the medical group and hospital operations.

Workflow Considerations for MIPS Implementation

Oncology providers will need to select metrics to report on 3 categories. The fourth category, cost, is claims-based. Below are the 4 categories that now constitute the MIPS composite score. The CMS QPP website displays this information, with filters, to aid providers.

1. Quality.

Determine which 6 quality metrics will be most appropriate for your oncology practice (5 process and 1 outcome). Ensure that the reporting mechanism is validated, such as via an approved third-party vendor. Consider adding back-up metrics in case there are obstacles to reporting and to optimize overall performance. Close communication between the informatics and clinical care teams may help align efforts and confirm that there is a mechanism to capture data in a discrete and automated fashion to facilitate reporting metrics in a compliant manner.

2. ACI.

The ACI metric includes 3 subsections. Choose to submit up to 9 measures: protecting health information, e-prescribing, health information exchange (HIE), providing patient access, patient education, view/download/transmit, secure messaging, medication reconciliation, and an immunization registry. In order to optimize performance, certain metrics may require changes in workflow. For example, for HIE, workflow changes may need to be made to establish secure connections with outside entities.

3. IA.

Select 4 IAs for your individual or group practice (2 medium and 2 high) that have strategic importance to your organization. These IAs are attestations. Several of the CMS IA choices align with planned improvement efforts at Moffitt.

4. Cost.

Although cost will not be a component of MIPS in 2017, oncologists can work with their financial analytics team to better understand the baseline information of the practice so it will be better prepared for 2018 and beyond. The Quality and Resource Use Reports can provide benchmarked data with respect to quality and cost, based on prior selection of quality metrics.6 Other initial strategies can focus on developing an understanding of unnecessary care variation. Working off common care pathways may help dampen unnecessary variation when possible. Due to the heterogeneity inherent in complex cancer patients, pathway adherence can be challenging.

Workflow Considerations for Advanced APM Implementation

The first step is to determine if the practice is eligible for an advanced APM and satisfies necessary criteria. The OCM is the only advanced APM offered by CMS for cancer care; it has a focus on chemotherapy. OCM participation requires providers to first meet the standard advanced APM requirements, such as 24/7 access to a qualified provider and medical records, monitoring of data to improve quality, and use of EHRs. In addition, OCM participants must provide patient navigation, document a 13-point care plan using the IOM recommendations, and provide care consistent with recognized guidelines.7 Payment is based on quality measures similar to those of MIPS.

An advanced APM requires assumption of a more-than-nominal financial risk. When implementing a bundled payment arrangement, there are 3 major categories to consider: degree of physician alignment, operational preparedness and maturity, and engagement of a payer partner.8 For the purposes of this discussion, the payer is the federal government: arrangements with a commercial payer may have more flexibility.

1. Physician alignment.

Alignment and engagement within the relevant group of oncology providers and between providers and their affiliated hospital is paramount. The decision to participate in an established advanced APM, or to develop one through the PTAC mechanism, depends on the active and willing participation of affected physicians. Advanced APMs may include payments that span the services of multiple providers and ancillary services, and there may be downstream impacts for the hospital. Physicians, in conjunction with the hospital, will need to develop the scope of services for the APM and agree on protocols. Hospitals will require resources and expertise to perform complex clinical and financial analytics to understand the major factors and variables impacting the total cost of care. Oncologists will need to commit to dampen unnecessary variation in a multitude of evaluation and management decisions. While oncologists need to put the patient first and provide high-quality, evidence-based care, minimizing unwarranted testing and treatment should be emphasized and there should be provision for some degree of predictability.

The concept of taking on financial risk in medicine is particularly challenging for oncologists who understand the tremendous heterogeneity in cancer care and the potential for catastrophic clinical and financial impacts. Even in a well-defined population of patients with cancer with a narrow scope of services, outliers exist at a greater frequency and magnitude compared with more common conditions in population management. The relationship between the oncologist and hospital will also vary based upon local factors, past experiences, a model for employment and incentive compensation, and the quality of the leadership from both the physicians and hospital.

2. Operational preparedness.

Financial risk analysis and management. An important step is to perform modeling and sensitivity analyses to develop a clear picture of financial risk. Define, for example, the most significant and modifiable sources of risk and the potential frequency and magnitude of risk (eg, readmissions, pharmacy, length of stay, etc). Once a provider, group, or healthcare system enters into a risk-based arrangement, the provider must actively manage risk or else face an increased probability of either poor quality or inefficient resource utilization. This will likely require robust concurrent utilization review and a fully actualized and optimized case management program. Such strategies need to address issues such as unnecessary or inefficient testing, post acute care partnerships, palliative care services, and the capability and capacity to manage emergency care to minimize treatment with providers outside the APM.

Management of catastrophic outcomes or incorporating new resource-intense therapies requires consideration of stop-loss provisions or carve-outs. Risk tolerance should be defined and will vary based on the scale of enterprise, overall financial health, and APM scope. Implementation of an advanced APM will also incur a large administrative task of tracking patients, which will require constant diligence to assure efficient resource use and preventing unwarranted variation. Consistent and transparent provider feedback may enable successful implementation of the APM and improved cancer care management.

3. Flow of funds.

For an advanced APM spanning multiple providers and their hospitals, all parties must agree upon and understand the flow of funds, which should be distributed equitably—not just between hospital and oncology care provider, but among all the specialties and ancillaries involved. The following questions need up front clarification:

• Will there be a shared savings component? How will it be disbursed?

• What will be the attribution methodology for poor performance (either quality or cost) with downside risk? What are the financial repercussions for each party involved?

• Will payment be prospective or retrospective, especially for future APM arrangements via PTAC?

Research and Education: Mission Critical

Research and education are more important than ever in oncology. The pace of change in the understanding of the mechanisms of cancer continues to accelerate. For example, recent advances in immunotherapy and targeted therapies will benefit an increasing number of patients. Such advances are enabled by partnerships that include the pharmaceutical industry, academic medical centers, and community providers. Innovative research, however, comes at a cost, and cutting-edge treatment is often more expensive than standard-of-care treatment. New payment reforms must allow oncologists and scientists to innovate and improve outcomes without risking insolvency and irrelevance. The complexity of modern treatments demands years of rigorous training, and funding educational missions is critical to the development of a capable future workforce with sufficient capacity to meet the growing need.

An Uncertain Road Ahead

The QPP is designed to accelerate the transition from volume- to value-based payments, with a focus on quality outcomes, efficient resource utilization, and, ultimately, the assumption of risk. Stakeholders have significant concerns, including that the QPP is burdensome and complex, MIPS measures are not applicable or meaningful, and advanced APM options are limited. Other concerns relate to attribution, particularly with the quality and cost components of these payment models. Cancer patients frequently receive care across different providers or health systems. Additionally, the duration of time between diagnosis, treatment, and outcome is often quite long. Therefore, attribution requires thoughtful and careful consideration. In late 2016, the Office of the Inspector General performed an early implementation review of the QPP and cited 2 vulnerabilities: providing sufficient guidance and technical assistance to eligible clinicians; and developing adequate information technology systems for reporting, scoring, and making adjustments. With leadership changes at HHS and CMS, changes to the QPP are possible. Nonetheless, the basic tenets of payment reform are likely common to any healthcare leadership.

â—†

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

None.

FUNDING SOURCE:

None.

Sachin M. Apte, MD, MS, MBA, is associate chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida.

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE

Sachin M. Apte, MD, MS, MBA

Associate Chief Medical Officer

Moffitt Cancer Center Magnolia Drive

Tampa, FL 33612

E-mail: sachin.apte@moffitt.org.

Regardless of the uncertainty ahead, there is value in understanding and implementing the QPP, as the experience gained will be applicable to any future payment system aimed at pursuing value-driven care in oncology. Federal regulations will change and providers will need to pivot, but the needs of patients diagnosed with cancer will not stop. Despite the challenges posed by a dynamic cancer care landscape, the duties of an oncologist will remain to treat, cure, and comfort patients afflicted with an often relentless disease that is not beholden to any legislation. REFERENCES

1. Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population; Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz P, eds; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2013/delivering-high-quality-cancer-care-charting-a-new-course-fora-system-in-crisis.aspx. Published September 2013. Accessed February 20, 2017.

2. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine website. https://www.nationalacademies. org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%20 2001%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published March 2001. Accessed February 28, 2017.

3. Quality Payment Program: modernizing Medicare to provide better care and smarter spending for a healthier America. QPP website. https://qpp.cms.gov/. Accessed February 28, 2017.

4. PTAC [Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee]. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/ptac-physician-focused-payment-model-technical-advisory-committee. Updated December 5, 2016. Accessed February 23, 2017.

5. 2016 Physician Quality Reporting System Qualified Clinical Data Registries. CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2016QCDRPosting.pdf. Published June 10, 2016. Accessed February 23, 2017.

6. How to obtain a QRUR [Quality and Resource Use Report]. CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/ Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeedbackProgram/Obtain-2013-QRUR.html. Updated January 11, 2017. Accessed February 23, 2017.

7. Patel M, Patel KP. The Oncology Care Model: aligning financial incentives to improve outcomes. Onc Pract Manage. 2016;6(12). Published December 2016. Accessed February 28, 2017.

8. Lee JC, Welter TL. Bundled payment program development—implementing the program. Becker’s Hospital Review website. http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/bundled-payment-program-development-implementing-the-program.html. Published August 25, 2015. Accessed February 23, 2017.

9. Murrin S. Early implementation review: CMS’s management of the Quality Payment Program. Office of Inspector General website. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-12-16-00400.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed Accessed February 28, 2017.