- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Similar Barriers Impact Population Health and Cancer Care Access, Panel Says

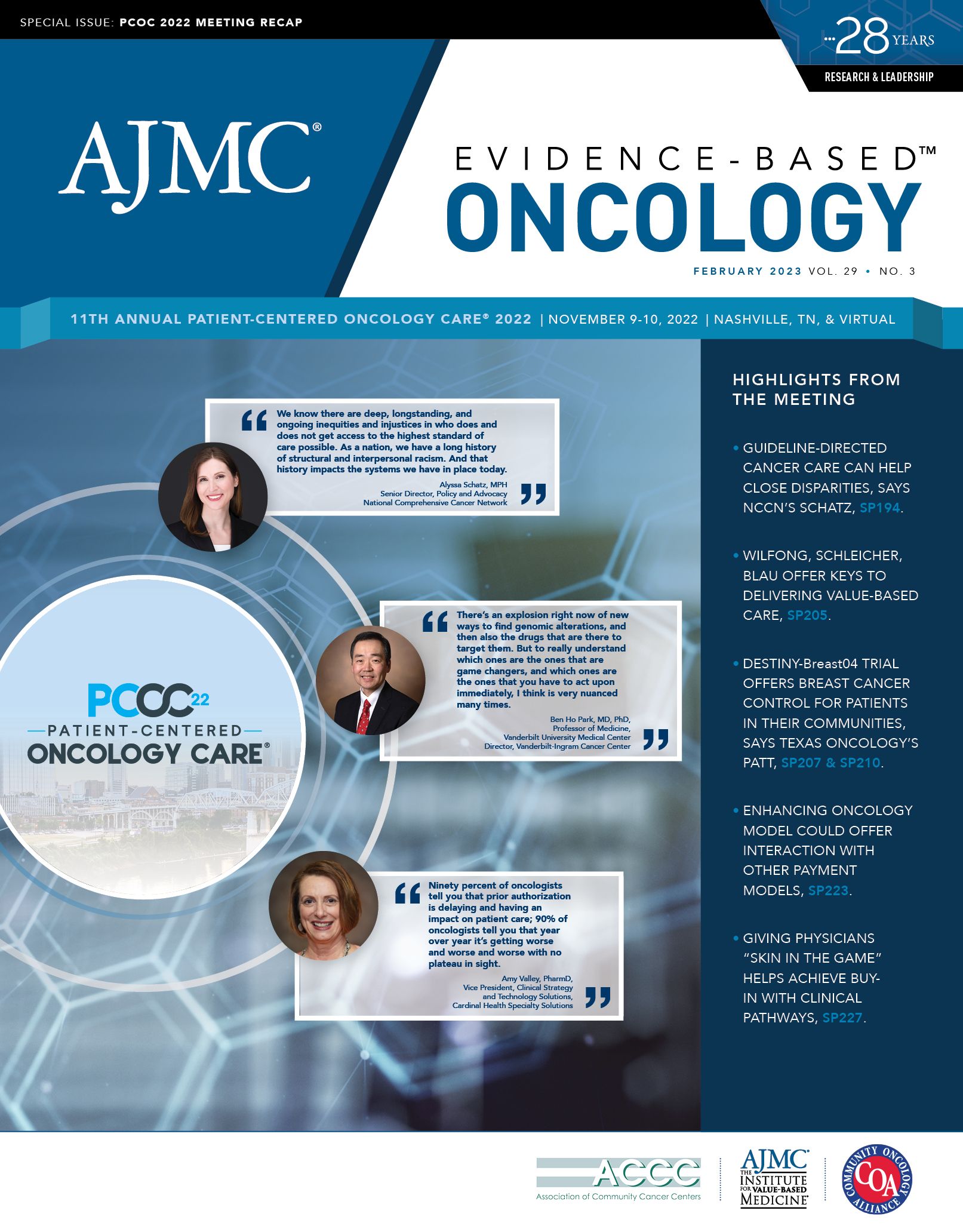

Strategies such as preventive screenings in the overall population and personalized therapy approaches for patients with cancer have been widely accepted as effective by oncologists. However, these aspects of cancer care are not always considered necessary from the payer perspective, according to a panel discussion held during the 11th Annual Patient-Centered Oncology Care® conference held November 9-10 in Nashville, Tennessee.

The panel was moderated by Joseph Alvarnas, MD, meeting cochair and vice president of government affairs, City of Hope, and chief clinical advisor, AccessHope, in Duarte, California. Alvarnas is also editor in chief of Evidence-Based Oncology.™ The panel included:

- Debra Patt, MD, PhD, MBA, executive vice president of Texas Oncology in Austin;

- Katharine A. Rendle, PhD, MPH, implementation and behavioral scientist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia;

- Neil Iyengar, MD, associate attending physician, breast medical service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, New York; and

- Robert Groves, MD, executive vice president and chief medical officer at Banner | Aetna.

Panelists focused largely on the barriers to improving population health and the logistics of making cancer-specific care available to historically underserved communities. “Oftentimes, at least in my practice and discussions, I find an extraordinary tension between the population health lens and patient access to care,” Alvarnas said. “And this idea of a triple aim of care that seems highly genericized is really at odds with personalized medicine. I struggle to navigate that tension point to get payers and other stakeholders to think differently about this.”

Role of screening. Patt stressed the importance of resource availability for patients who may benefit from targeted therapies and other innovations. But from a population health standpoint, encouraging screening and prevention is an integral aspect of care, she said.

Screening rates dropped an estimated 40% to 90% at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with previous years,1 Patt added. Although these rates have recovered somewhat since then, there may be longer-term repercussions in the form of more advanced cancers in the coming years.

Groves raised the question of whether drops in screening rates during the pandemic would make a difference in cancer outcomes. For example, he said some data have suggested that advances in treatment, not mammography, have improved outcomes in breast cancer. “The other risk that we’re not taking into account when we’re talking about these things is the financial harm that can be done to patients, families, and societies. All these things have to be factored into this,” Groves said.

The impact of COVID-19 screening reductions would not be evident for some time, according to Patt. “I think that we can’t look at 2- or 3-year outcomes in screening and anticipate that we will see the outcomes of delays. That would be like saying, ‘If I’ve smoked for 3 years and don’t have a lung cancer, I’m not going to get it,’” Patt said. “Because the window of the outcome of stage migration and increased mortality takes a longer lens.”

Barriers to preventive care. Barriers vary based on cancer type, but some basic commonalities are awareness and knowledge. Many patients do not know about lung cancer screening or do not realize they are eligible, Rendle said. Access to care is another issue, with structural components such as clinic location playing a part in reduced screening rates.

Rendle also highlighted the importance of strategizing to create systems that serve all populations rather than systems that consider certain populations to be at a deficit. No matter the barrier, the system should be responsible for facilitating access to care for every individual. “Putting the onus on the system and thinking about empowerment rather than filling deficits in communities…that shift away from the individual being the problem [and recognition] that you need to help and…get them to the table help shift the focus,” Rendle said.

Patt reiterated the need for patient awareness about cancer screening, noting that primary care physicians are integral in guiding patients to receive screenings. She noted that proposed cuts to the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) could limit primary care access to the Medicare population. The fiscal year 2023 Omnibus Appropriations bill, signed on December 29, 2022, offered partial relief to the PFS schedule that had been finalized on November 1, 2022.2

Population health and risk factors. Iyengar noted that another pandemic, obesity, is putting an increasing number of Americans at a higher risk for cancer. Obesity, he said, is independently correlated with cancer risk, and the panel agreed that this public health issue is another instance where targeted messaging for communities at high risk of cancer is needed.

Although racial and ethnic minority communities are disproportionately affected by obesity, current approaches are not geared toward these populations, according to Iyengar. The goal is not necessarily to dedicate more resources to obesity-related cancer prevention but to tailor recommendations based on the individual patient and identify community providers who can play a crucial role in cancer prevention.

In a series of studies at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, he said, it was found that the obesity-related pathophysiology that affects carcinogenesis happens differently depending on ancestral heritage or lineage and environmental exposures. “The differences that we’ve identified biologically, with regard to the impact of obesity on carcinogenesis, are remarkable, and they’re clearly identifiable,” Iyengar said. “We can incorporate this from a precision medicine paradigm by using population-specific biomarkers while also accounting for the population health approach to these disparate populations.” Groves added that in historically underserved populations, strategies to boost community engagement and education are key in shifting the paradigm from a system based on rescue medicine to one based on prevention.

Economics. Some aspects of improving cancer care, such as social workers and additional support measures for patients, are not reimbursable services, Alvarnas noted. With the Oncology Care Model (OCM) having lapsed, Patt highlighted the complicated economics of transitioning after significant investments to make OCM successful and reduce hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

“What I’d like to see happen is [for us] to come to the table with our commercial payers and say, ‘Look how these 5 years have gone. Look what we’ve done. This is an investment that we’ve made. We are a great investment for you, and let’s work together to improve the health of this population we share together,’” Patt said.

The answer is not simple. Part of the challenge is that long-term prevention strategies do not typically offer a short-term return on investment for payers, Groves said. This gives payers less incentive to cover additional preventive interventions. Thinking of ways to finance health insurance—especially commercial health insurance—over the long term without a need for short-term return on investment is key, he added.

“One of my hopes is that through precision medicine, we can get better at identifying the populations that will benefit most from screening, using Bayesian logic: the higher the pretest probability, the more likely you are to get a valid result,” Groves said. “I think a one-size-fits-all approach is not nearly as effective as understanding the nuance so that we only screen populations who can benefit from that screening.”

Considering the relatively narrow population that genomics has been studied in, Alvarnas raised the question of whether there is a path forward that accounts for both more equitable genomic understanding of the overall population and the creation of rules and guidelines that can be applied at scale. Increased research and novel surrogate markers that can be addressed in a way that delivers quick results, Iyengar said, could play a role in the implementation of intervention and prevention strategies sooner rather than later.

References

1. Jabbal IS, Sabbagh S, Dominguez B, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer-related care in the United States: an overview. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(1):681-687. doi:10.3390/curroncol30010053

2. How the 2023 Physician Fee Schedule impacts emergency medicine groups. RevCycle Intelligence. Updated January 4, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2023. https://bit.ly/3XyqhqP