- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

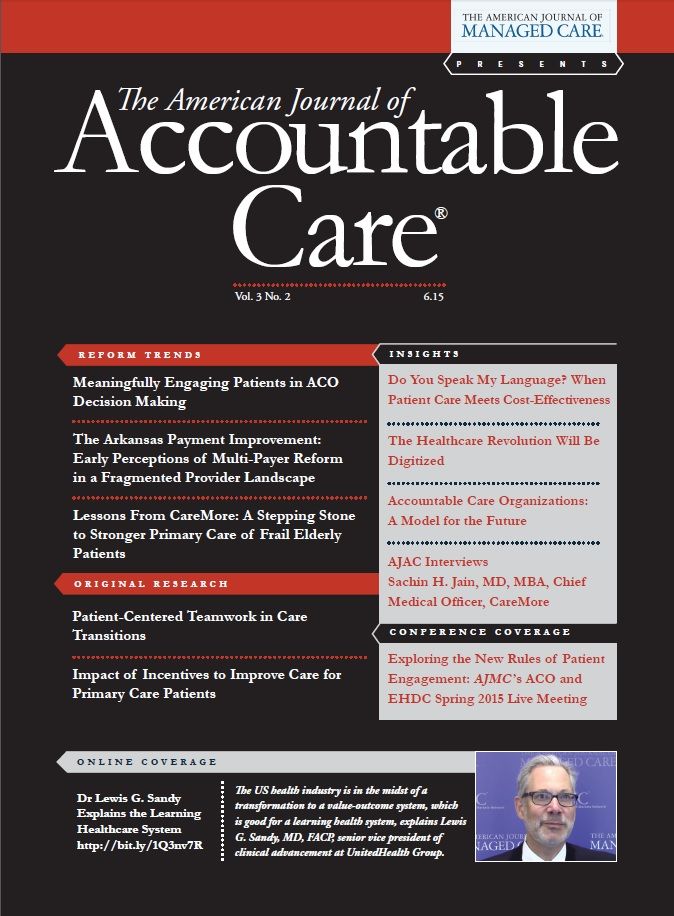

AJAC Interviews Sachin H. Jain, MD, MBA, Chief Medical Officer, CareMore

The American Journal of Accountable Care recently interviewed Dr Jain about his decision to join CareMore, CareMore's innovative care model, and his perspectives on US healthcare.

Sachin H. Jain, MD, MBA, recently joined Anthem’s CareMore Health System as its chief medical officer. CareMore is an innovative healthcare delivery system that originated in southern California but now extends to 7 states and cares for over 100,000 patients in the Medicare Advantage and Medicaid programs.Dr Jain was previously chief medical information and innovation officer at Merck, Inc, a lecturer in healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School, and an attending physician at the Boston VA Medical Center. Previously, he was special assistant to the national coordinator for health information technology; senior advisor to CMS; and a member of the faculty at Harvard Business School. Dr Jain is also an editorial board member of The American Journal of Managed Care.

The American Journal of Accountable Care recently interviewed Dr Jain about his decision to join CareMore, CareMore’s innovative care model, and his perspectives on US healthcare.

AJAC: What do you see as the biggest issues in American healthcare?SHJ: For years, there was a stark, unmistakable void in US healthcare: access to care and coverage. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act, we are quickly moving onto improving the delivery system. We are haunted by the huge gap between the potential of what we know we can deliver to patients and the reality of what they receive in practice. We know instinctively that we can do better, yet we struggle with how to do so.

AJAC: You recently joined CareMore as chief medical officer. How did you end up there?SHJ: A few years ago, while working as part of the team launching the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, I had the opportunity to get to know organizations in the vanguard of improving the value of care: namely, organizations that were successfully working to do more for patients with less. Among these was CareMore.

AJAC: How is patient care at CareMore different from patient care in other leading healthcare systems?SHJ: The value of a system like CareMore is perhaps best understood in contrast. When I was a physician in Boston, I had the pleasure of taking care of woman we will call Elizabeth Owens (name changed to protect patient privacy). Ms Owens was well known to most of the other physicians because she was sassy and had a sharp tongue—and spared no opportunity to use it.

Her hospitalizations were varied in their causes: one time it was cellulitis that progressed into a non-healing ulcer; another time it was hyperglycemia and congestive heart failure; and yet another time, it was blocked dialysis access.

Nothing we ever did seemed to work. She seemed to be in the hospital almost as often as we were. I will always remember another physician remarking to me about Ms Owens: we can cure her difficult medical problems, but we can’t fix her difficult life. This was the type of frustration and philosophizing that Ms Owens would prompt.

Now, over time, I was able to get to know and bond with Ms Owens and I came to understand that her problems were as much social as much as they were medical.

She was lonely and frustrated. She could never make her outpatient appointments because she had no one to bring her to them. She had a fundamentally poor understanding of her diseases, her therapies, and her care, and she was frustrated by a system that never seemed to give her what she needed to stay well—but was more than happy to hospitalize her when things became bad enough. Anyone who has spent time in the trenches of care delivery knows that patients like Ms Owens populate our nation’s healthcare system—patients whose needs are part medical, part social, and entirely unaddressed by our dominant models of care. Ms Owens had good insurance; she had access to America’s best hospitals and top-notch clinicians, yet somehow they were all ineffective.

At CareMore, Ms Owens might have had regular access to a nurse practitioner who could visit her home as the need arose. She would have regularly visited a community-based comprehensive care center with integrated disease management programs for the most common chronic diseases of the elderly. She might never have been admitted for heart failure because measurement of her weight by tele-weight scale would enable medication adjustments before her condition worsened. She might never have lost her dialysis access because of the regular maintenance and cleaning administered. She might not have missed her appointments because she would have been given transportation to and from. And she might not have suffered a non-healing ulcer because the wound care and prevention program would have aggressively managed it so that it did not become bad enough to require hospitalization.

And on the rare instance where she did need hospitalization, she would be treated by an extensivist physician who would not just see and manage her in the hospital, but also during her rehabilitation facility stay and subsequently in clinic to follow up. That physician would have time for her—because for producing understanding in a patient, there is no substitute like time.

The typical errors at hand-off—medication errors and discontinuities in her care plan—would be less frequent because care would be consistently delivered by a well-functioning, highly organized team that has built the institutional memory necessary to deliver high-quality care.

AJAC: As a health system caring for vulnerable populations, how is CareMore working to eliminate healthcare disparities?SHJ: The amazing thing about CareMore is we focus on the frailest elderly and we work in communities and populations that actually need us. Fifty percent of our patients actually speak Spanish. We work in some of the poorest communities of southern California, Nevada, Arizona, and Tennessee, and so I think there are opportunities for us every day to close healthcare disparities.

AJAC: How are the clinical outcomes?SHJ: I don’t want to be disingenuous and pretend that CareMore is perfect and everything would have gone exactly as I just described 100% of the time—far from it. We have the same challenges other clinical organizations do around the consistency and reliability of the clinical model.

Yet, we know that compared with other Medicare cohorts, we consistently deliver lower clinical utilization and better clinical outcomes. Across our end-stage renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic heart failure patients, our patients experience significantly fewer hospitalizations and admissions.

Our average lengths of stay, admission rates, and readmission rates are roughly a third of national Medicare benchmarks. The average CareMore member with stage 3 chronic kidney disease progresses to dialysis in slightly over 24 years, as opposed to less than 6 years for an average Medicare patient.

The average CareMore member enrolled in our diabetic care program has a glycated hemoglobin of 7.0.

And importantly, most patients and their families are thrilled with their experience of care, the high level of engagement, and the high level of touch they receive. In my first week on the job at CareMore, I was surprised when I learned that the widow of a CareMore member sent an invitation to her husband’s funeral to our CEO, Leeba Lessin—remarking what an important part of her husband’s life CareMore had been and thanking her for it.

AJAC: How does the culture at CareMore differ from others you’ve experienced?SHJ: Perhaps the most significant aspect of CareMore’s philosophy is a persistent willingness to thoughtfully challenge the status quo. Medical and nursing training typically teaches us to operate and manage within a fixed, unchanging system. It trains for skill, not for leadership.

In the training programs we administer to our staff at the CareMore Academy, we are constantly pushing our clinical staff to ask “why” and challenge prevailing ideas to optimize care for patients. Does every patient with chest pain truly require a cardiology consult? What care can safely be delivered by a medical assistant? And what care truly requires a physician’s input? What hospital services can be safely delivered at home?

This willingness to challenge the status quo leads us to interesting places. It leads us to new medical roles—like the extensivist that I spoke of. It leads to a view of primary care as much more of team-based outbound activity than a singularly practiced inbound activity. It leads to a view that a confident, well-trained generalist is often far preferred over a network of ill-coordinated specialists. And it leads to a view that prepayment in the form of capitation enables freedom to do what is right for patients rather than risk.

Additionally, it leads to a view that patient nonadherence is CareMore’s problem, not the patient’s problem. It leads to a view that early proactive intervention is far superior to managing a problem when it has progressed to requiring hospitalization. These types of attitudes are decidedly nontraditional, but they are common sense. They challenge the prevailing views of the medical establishment, but it is from challenging these long-held views—and the innovations that follow—that most CareMore clinical staff derive their strength and persistence. It is what makes CareMore, CareMore.

AJAC: What did you learn from your roles in the government with CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator that you hope to apply at CareMore?SHJ: I think one of the amazing things about being in the government at the time of the HITECH Act as well as the Affordable Care Act was seeing the speed in which change could actually happen. I think typically we think of the government as being slow and deliberative, but in fact, when done right, the government can create huge change and positive upheaval for the healthcare delivery system. So a lot of how I’m thinking about what we need to do at CareMore is, “How do you actually create that positive upheaval that’s going to generate the upward movement to improve healthcare delivery?” CareMore has a very proud history of being an innovative system—I like to say that it has innovation in its bones. It’s really about unleashing that and refocusing on that, and we’ve had a tremendous couple of months since I’ve joined. One of my passions for a long time has been diabetes prevention, largely because of my personal and family experiences with diabetes. The amazing thing is watching the speed at which our organization can actually take an idea from concept to reality. We started talking about diabetes prevention in February, we started designing what it would look like on a system level in March, and on June 1 the diabetes prevention program went live at CareMore.

I think one of the things we need to systematize more broadly is to think about our pace of change and how we can actually accelerate the speed of change. That was something I learned in government that is finding its way into CareMore every day.

AJAC: What does the future hold for American healthcare? What does the future hold for CareMore?SHJ: In the coming months and years, healthcare will change dramatically with the introduction of new diagnostics and new therapies. But I believe it is new systems of care—supported by new philosophies of care—that will have the biggest impact on improving healthcare outcomes.

CareMore, over the past 2 years, has undertaken a journey to transmit its model to other systems and settings—such as our flagship partnership with Atlanta’s Emory University Medical Center—and to other types of patients other than just the frail elderly, including poor young people who are part of the Medicaid program in Tennessee and Ohio. We have created 2 new divisions—CareMore Inside and CareMore Essentials—to enable these transformation initiatives. As we work to spread CareMore’s model and philosophy of care in the United States, we are looking for partner organizations that share our ambition.