- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

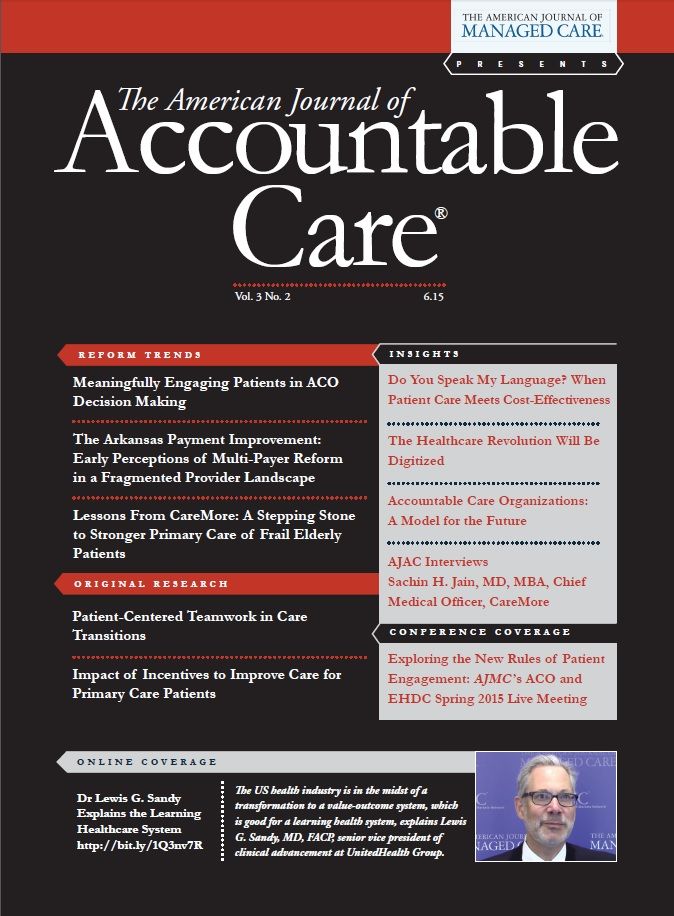

Exploring the New Rules of Patient Engagement: AJMC's ACO and EHDC Spring 2015 Live Meeting

As accountable care organizations (ACOs) work to deliver population health, patient satisfaction, and cost savings, the need to engage patients as partners in their own healthcare has never been greater. The ACO and Emerging Healthcare Delivery Coalition convened April 30-May 1, 2015, at the historic Hotel del Coronado in San Diego, California, to explore ways to make patients the starting points of healthcare, not just its recipients.

The heads nodded in recognition as Howard C. Springer shared the story of the patient and the bathing suit. Springer, the administrative director of strategy for accountable care services for Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, had just finished explaining how he makes the finances work as he integrates behavioral health services into primary care, but the tale of breaking through with a patient with multiple chronic conditions who could not go to swim class for lack of a bathing suit really hit home.

Many on hand at the third live meeting of the ACO and Emerging Healthcare Delivery Coalition had heard of patients like Springer’s or even dealt with them every day, so they knew it was uncommon for a healthcare provider to do what Swedish did: it paid for the bathing suit in order to get the patient moving.

These are the stories behind the data, and attendees shared them over 2 days at the historic Hotel del Coronado in San Diego. Accountable care organizations and large employers described how they are moving beyond the walls of the hospital or the clinic to meet patients where they are, and they must if health systems are to achieve the “triple aim” of better population health, improved patient satisfaction, and cost savings.

“How do we engage people in their own healthcare?” asked Coalition Chair Anthony Slonim, MD, DrPH, as he opened the meeting. Slonim, president and CEO of Renown Health in Reno, Nevada, set the tone for the speakers, panel discussions, and small-group workshops, as well as for networking time with fellow members.

Small Numbers, High Costs

For years, CMS has known that a sliver of the Medicaid population accounts for a disproportionate share of healthcare spending; in May, a report from the Government Accountability Office found that 5% of the Medicaid-only clients accounted for more than half of the costs for 2009 to 2011.1 Getting this group—which includes patients with diabetes, asthma, substance abuse, and mental health conditions—to engage in better self-care won’t happen by waiting for them to take proactive steps such as going to see the doctor or changing their behavior. Rather, the experts agreed it is up to the healthcare system to go find them.

“This is not the flavor of the month—it is part of healthcare today,” said Rowena Bartolome, RN, PHN, MHA, national program leader, quality and equitable care, Kaiser Permanente. But doing this demands a fundamental shift in thinking from stakeholders across the healthcare spectrum. Delivery systems that for decades have been designed around doctors’ wishes must be reengineered based on what patients want, and so far, progress is uneven. Several speakers at the San Diego meeting said community partnerships with senior centers, churches, or social service agencies make sense but take work, because these entities are not set up for healthcare delivery, HIPAA compliance, or billing.

The payoff, according to Tabatha Dragonberry, MEd, RRT-NPS, AE-C, ACCS, CPFT, C-NPT, is the opportunity to address barriers to better health that would otherwise go undiscovered. Dragonberry, who represents the Allergy and Asthma Network and is a clinical educator with Valley Children’s Hospital, offered an example: a social service agency might ask, “Do you have roaches in your home?” The patient might reveal that the landlord put out poison, but the infestation persists. In a case like this, a new place to live might eliminate both the roaches and some health issues, too.

Slonim noted, and others agreed, these patients in extreme poverty live with immediate crises that fundamentally affect their health. “If you’re worried about walking out the front door and being shot, it takes priority over going to get your colonoscopy,” he said. Realities like violence, addiction, and schizophrenia that create homelessness are issues the healthcare system must work with, and states and counties must address, he said; in the past, these were not healthcare problems until someone walked into the emergency department.

“We’re moving from a high-cost sick care system to a high-value wellness system,” Dragonberry said. With high risk patients, “We need to know, ‘What are their daily behaviors? What time do they take their medicine? What is going to hinder them from not doing these things?’”

It is a tall order, but health systems generally, and ACOs in particular, know the clock is ticking. Both the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and goals outlined this spring by CMS will require that payment be connected with healthcare quality. The first hurdle will come in 2016, when 30% of Medicare payments will need to be be value-based,2 and the legislation passed to eliminate the sustainable growth rate will also push physicians toward value-based reward structures.3 CMS wants 50% of Medicare payments to be value-based by 2018.2

In this new landscape, the speakers said, financial success and even survival—will require healthcare providers to find better ways to involve patients in their own care, but without driving up costs. “We need to be more effective in patient engagement, but we need to do this in a way that is not labor intensive on the payer side,” said Ira Klein, MD, MBA, FACP, senior medical director, National Accounts, Clinical Sales and Strategy at Aetna.

Failing to engage patients will have other costs. As reimbursement is tied to population health, providers and ACOs that fail to meet targets will end up in disputes, which may stem from contracts that fail to address differences in patient populations; mediation can offer a better way to resolve disputes between providers and the ACO. Thus, patient engagement is so important that it could be the fourth part of a “quadruple aim,” said Leonard Fromer, MD, executive medical director, group practice forum and assistant clinical professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of California.

From “Managing Costs” to “Managing Care”

“Ninety-nine percent of health outcomes are not related to healthcare,” said Kyu Rhee, MD, MPP, vice president of Integrated Health Services for IBM Corporation. Factors such as diet, exercise, the environment, and socioeconomic status all contribute to health outcomes—and always have—but the rise of ACOs has brought them under the purview of healthcare systems.

For years, Rhee said during a presentation, rising healthcare costs have limited hiring and the size of raises, thereby forcing employers to become more engaged in the health of workers. Now that the ACA has defined what employers must pay, more costs are being shifted to workers.

The healthcare industry, Rhee said later, must find “prescriptions for things that are not traditionally part of healthcare.” He described the transition as the difference between “managing costs and managing care,” which means changing the mindset from finding a place to shift the financial burden to reducing the healthcare burden in the first place.

As he led a small group session, Rhee discussed the role of technology and whether it could give health plans more real-time insight into their enrollees’ behavior, enabling and encouraging them to change it. For example, what if a health plan could see what foods you buy at the grocery store? Is that information that a health plan would want to have?

Attendees were intrigued but also skeptical at the thought of the volume of information that would flow from using such technology. Who would store it? Who would interpret and manage it? How could it be boiled down and presented in a meaningful way to the provider?

Participants agreed that there is an abundance of data already, but also a great need to connect it. “When we look at the market today, Medicare has data, and the commercial payers have data, but it sits in all these silos,” said Sachin Jain, BTech, MBA, chief executive officer for Carrum Health. “It’s very difficult to pull down, even for a large employer.”

And yet, personal technology may hold the key for engaging some populations—especially young Americans. Some attendees said they are showing a preference for nontraditional healthcare delivery and nontraditional settings, such as retail outlets and pharmacies.

Nevertheless, whether help from technology comes in the form of add-ons for electronic health records, apps for smartphones, or wearable technology, an important rule applies: “If you go outside the normal work flow to engage patients, you are in tough shape,” Klein said.

The Role of Behavioral Health

The approach that Springer is bringing to Swedish stems from a reality borne out by data: patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes who also have a behavioral health problem, such as depression, are less likely to eat well, exercise, or follow instructions for medication. Until the behavioral health issue is addressed, change is unlikely.

“For the source of the problem, we don’t have to go very far,” Springer said. About 80% of patients with behavioral health diagnoses first show up in a primary care setting; of these, 60% to 70% receive no treatment. Historically, the primary care setting has not been set up for their needs, he explained.

“Behavioral health cases are flow busters,” he said. When a practice’s financial structure under fee-for-service depends on office visits lasting 7 to 15 minutes, there’s no capacity to deal with a patient opening up about sexual abuse or symptoms of a mood disorder, so these patients have historically been referred to a specialist. Payment models from before the ACA and the federal parity law, which carved out mental health from the rest of the medical benefit, promoted this practice. Additionally, the trouble is—as research pioneered at the University of Washington has shown—most patients don’t act on the referrals, so problems just get worse.4

Springer’s work at Swedish has involved integrating the behavioral health component into the primary care setting, so the barriers to self-care in hard-to-treat patients are handled in an integrated way. While research has shown that this approach can ultimately reduce healthcare costs on a per patient basis,4 getting it to work on the ground has, as Slonim described it, required much “creativity” on Springer’s part. In a series of slides, Springer outlined how he has leveraged grants to fill gaps as Medicare and Medicaid transition from fee-for-service to value-based reimbursement; during a panel discussion that followed, he and Slonim discussed how Swedish is making the model sustainable as the grants expire and value-based payment becomes a bigger part of the picture.

Getting the payment models to match the goals that CMS espouses is problematic, the panelists agreed. Jennifer Lenz, assistant vice president, Quality Solutions Group, California, National Committee for Quality Assurance, acknowledged that getting quality metrics and CMS’ own reimbursement standards into alignment can be very difficult, and this lack of consistency can limit innovation.

The challenge is changing the thinking of staff who have spent most of their careers in a fee-for-service system. “Changing perspective is key,” Springer said. Swedish entered into a contract with Boeing, the area’s largest employer, which demanded that staff not keep Boeing employees in the hospital any longer than necessary. It changed how hospital staff operated. Klein said he’s seen it happen. “One of the lessons I’ve learned is, when people are clearly accountable, they will find a way to make it work.”

ACOs Are Creating Change

Despite these hurdles, ACOs are driving change, although it is too early to declare any single new payment model superior to all others, said Suzanne F. Delbanco, PhD, executive director of Catalyst for Payment Reform. Things have come a long way since 1999, when the Institute of Medicine issued the groundbreaking report on the hospital safety crisis, To Err is Human.5 “No one wanted to believe it,” Delbanco said.

“It’s much more accepted today that quality does vary,” she said. “We know when we buy healthcare, we’re not getting the same healthcare every time we write a check.”

The new era of transparency is uncovering the wildly different prices that patients and payers are charged for the same tests or services in different hospitals, with price having no apparent connection to quality. Experimentation with new payment models has thus far mostly involved incentives for meeting quality and savings targets; there is no unknown financial risk. Conversely, there has been less work with 2-sided risk models.

There has been a lot of movement toward the Patient-Centered Medical Home, although the jury is out on whether the model works, Delbanco said. The bundled payment model—in which providers are given a set fee for a procedure or service—can “hold tremendous promise, but it is so hard to implement.” Payers who attempt it are ending up with the staff processing payments by hand, she said.

More Coming This Fall

As ACOs and other emerging delivery and payment models evolve and move away from traditional fee-for-service system models toward cost-effective and value-based care, the need to understand how these models will evolve is critical to building long-term strategic solutions.

The mission of the ACO and Emerging Healthcare Coalition is to bring together a diverse group of key stakeholders, including ACO providers and leaders, payers, integrated delivery networks, retail and specialty pharmacy, academia, national quality organizations, patient advocacy, employers, and pharmaceutical manufacturers to work collaboratively to build value and improve the quality and overall outcomes of patient care. Coalition members have the opportunity to share ideas and best practices through live meetings, Web-based interactive sessions, and conference calls; distinguishing features include the Coalition’s access to leading experts and its small workshops that allow creative problem-solving. Since The American Journal of Managed Care launched the Coalition in early 2014, membership has grown to over 200 members.

The fall 2015 live meeting will be October 15-16, 2015, at Innisbrook Resort in Palm Harbor, Florida, with topics to include specialty pharmacy, oncology medical home models, pain management in an ACO, and emerging innovations around pharmaceuticals for ACO patient populations.REFERENCES

1. Joszt L. Small proportion of Medicaid enrollees account for half of expenditures. AJMC website. http://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/Small-Proportion-of-Medicaid-En- rollees-Account-for-Half-of-Expenditures. Published May 12, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. Better care. Smarter spending. Healthier people: paying providers for value, not volume [press release]. http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/ Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26-3.html. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2015.

3. Caffrey MK. Obama signs legislation to replace SGR with Medicare reform. AJMC website. http://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/Obama-Signs-Legislation-to-Replace- SGR-With-Medicare-Reform. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2015.

4. Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illness. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611-2620.

5. Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine; National Academies Press; 1999. https://www.iom. edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20 Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More

Blister Packs May Help Solve Medication Adherence Challenges and Lower Health Care Costs

June 10th 2025Julia Lucaci, PharmD, MS, of Becton, Dickinson and Company, discusses the benefits of blister packaging for chronic medications, advocating for payer incentives to boost medication adherence and improve health outcomes.

Listen