- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

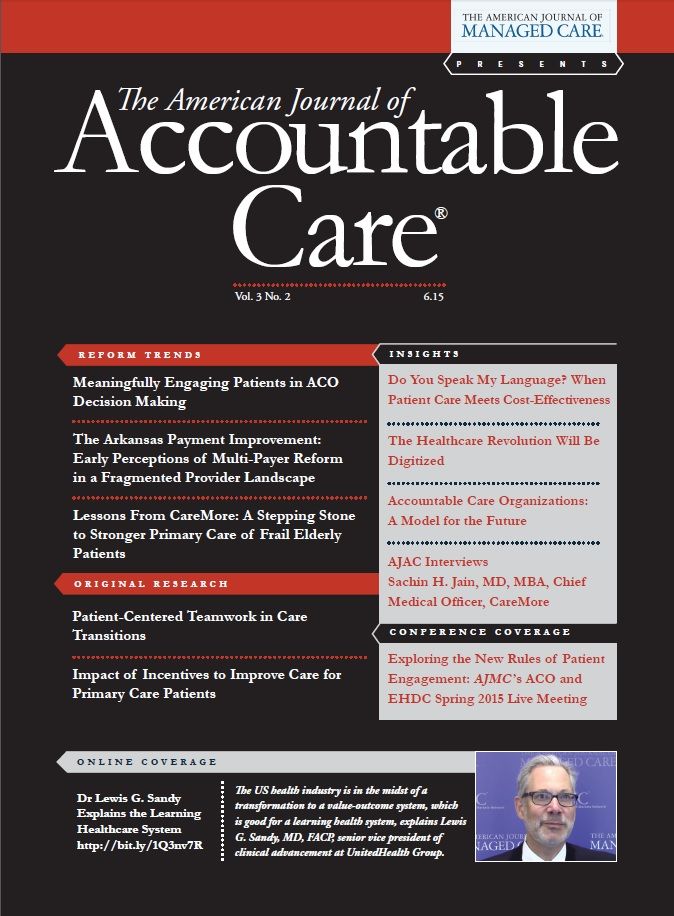

Accountable Care Organizations: A Model for the Future

This manuscript describes a structural alternative that builds upon the vision of the ACO, positions it centrally in the healthcare experience, and overcomes current limitations in delivering care.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law by President Obama 5 years ago. Among the many components of the ACA was an element focused on healthcare reform, under which, was the funding for accountable care organizations (ACOs).1 ACOs are all organized very differently, but the major attributes include responsibility for the quality and costs of care of an assigned population.

One of the major programs under the ACO framework sponsored by CMS was the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), which provided an opportunity for healthcare organizations to learn how to advance the ACO model.1 While there was considerable hope that ACOs would advance the value proposition of improved quality of care at lower cost, the results to date have not fully realized the improvement in quality outcomes or the reduction in cost.2

There are likely several reasons for these limitations, including fully engaging physicians, engaging participants, and connecting physicians and participants adequately through information technology, as well as unknown and highly variable compensation mechanisms that fail to justify a behavioral change by physicians, and temporal separation between the requested behavioral change by the physician and any potential payment. In addition, the ACO concept is fundamentally at risk of not achieving its outcomes as long as payers, and not ACOs, remain responsible for distributing the payments to providers and health systems.

This manuscript describes a structural alternative that builds upon the vision of the ACO, positions it centrally in the healthcare experience, and overcomes current limitations in delivering care. In northern Nevada, we have a horizontally and vertically integrated healthcare delivery system, an MSSP ACO, and substantial market share. We are further differentiated by owning our own health plan. We believe that the following approach will help us to care for the people and communities we serve.

Current State of Healthcare

Figure 1

In the current state of healthcare on the inpatient side, the physician orders care and the hospital management team delivers the ordered care (, Panel A). For example, if the physician orders laboratory or radiology testing, there is an infrastructure that assures the test is performed and the physician receives the results to further care for the patient. If surgery is needed, the patient is delivered to the appropriate operative setting where the surgical team cares for them and returns them to their room for recovery after the procedure is completed. Wound care, pharmaceutical care, and nursing care are all organized and delivered to the patient through the hospital management’s efforts. The payer reimburses the physician for professional services and the hospital for the care coordination activities of the patient’s stay. While there are still considerable opportunities to improve the efficiency and quality of inpatient care in the United States, this system functions in a relatively organized and coordinated manner (Figure 1, Panel A).

In contrast, the system of care on the outpatient side is currently in disarray and lacks coordination (Figure 1, Panel B). In this setting, when patients visit a provider for professional services, they receive a series of prescriptions for laboratory or diagnostic testing, medications, or potential consultations. The patient or family are responsible for the coordination of care when they leave the office and must figure out how to achieve all of the deliverables requested by the physician. In many circumstances, because of challenges in health literacy and payment delivery, the patient or family may not even understand what has been ordered, where to obtain it, or how it is to be paid for. The physician has neither the resources nor the education to coordinate the care, and does not receive payment for care coordination. Nonetheless, in the current system, the payer pays the physician for professional fees and every single intersection point where the patient experiences care (Figure 1, Panel B). At any point, the patient or family can determine that their care is not meeting expectations and go directly to the emergency department for evaluation, and the payer pays for that too.

Future State of Healthcare

In a newly designed healthcare system, there are 3 major components required for the delivery of care that capitalize on what an ACO may achieve.

Figure 2

First, consider the role of care networks (). A care network is a geographically distributed group of clinical services. The care network may be a physician group, a network of hospitals, a behavioral health network, a wellness network, a laboratory, or a radiology network. The network is responsible for care coordination based on the physician’s prescription in much the same way that the hospital is responsible for care coordination of inpatients. The modern healthcare system contains a series of these networks, but has never accepted responsibility for care coordination because there was no payment tied to the provided services.

Second, as with any ACO, physicians are an integral part of the equation. Physicians, regardless of who pays their salary, need to subscribe to the Triple Aim, including the best quality, service, and efficiency, as well as to assure access for all patients regardless of insurance type. This is important—currently, ACOs are organized based on payer type or population; for example, there are Medicare ACOs, Medicaid ACOs, and disease-specific ACOs emerging. Unfortunately, this approach is not scalable or sustainable. In order to be successful, the ACO needs to build an infrastructure to account for the needs of a geographically organized population, recognizing that there may be differences in care need from one geography to another.

Finally, once the care networks and the physicians are in place they need to be connected by information technologies, pathways, protocols, and guidelines. Only then will they be able to accept the risk for a population in quality and total costs of care. When this occurs, we have a fully functional ACO where impressive results can be achieved because the ACO assists in aggregating the care. For example, imagine 2 networks, one a network of primary care physicians and the second a network of behavioral health services and psychiatrists. When connected, the coordination of care is managed by the networks, which receive a fee for the coordination activities. Patients and families are pulled through their healthcare experience by the network, which assures that appropriate outcomes in quality and cost are being achieved. The payers now have only a single payment to make to the ACO, which is responsible for paying the professional fees of the physicians and a coordination fee to the networks of care.

Limitations to the Model

While this model helps to advance the care for our patients and drive the value proposition in healthcare, there may be limitations to broad generalization. First, our market is geographically limited, enabling our ability to execute on the model, but potentially limiting others. Second, we have a very well-developed health plan that enables our ACO to function as an integrated component of the healthcare network. While only a minority of health systems currently have a health plan, many are diligently pursuing such an option. Nonetheless, we are subject to the same challenges and limitations of healthcare reform for publicly insured patients. Third, we are working diligently with our physician colleagues to assure that together we can take the best care of patients by driving toward quality outcomes and service as efficiently as possible.

Despite the limitations of the model, we believe that the approach also has significant strengths, the most notable being the improved care coordination for patients and families managed by the networks of care. In addition, the development of networks allows us to capitalize on and deliver on our other responsibilities—including the social determinants of disease—for the people and communities we serve beyond those patients and families that seek their care with us. As a nonprofit organization, this helps to enhance the benefit we bring to the community.AUTHORSHIP INFORMATION

Author Affiliations: Renown Health (ADS, KG), Reno, NV; University of Nevada (ADS), Reno, NV.

Source of Funding: None.

Author Disclosures: Dr Slonim is a board member of Renown Health, where he is also employed; Renown Health is included as a part of the strategic planning efforts for this manuscript. Dr Slonim is a paid advisory board member for the ACO Coalition, and has also received lecture fees for speaking at pharma conferences. Mr Gillis is an employee of Renown Health, and has received lecture fees for various speaking engagements at the invitation of a commercial sponsor.

Authorship Information: Concept and design (ADS, KG); drafting of the manuscript (ADS, KG); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (KG); administrative, technical, or logistic support (ADS); and supervision (ADS).

Send correspondence to: Anthony D. Slonim, MD, DrPH, president and CEO, 1155 Mill St (Z6), Reno, NV 89502. E-mail: aslonim@renown.org.REFERENCES

1. 42 CFR Part 425 Medicare Program; Medicare Shared Savings Program: Accountable Care Organizations; Final Rule. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-11-02/pdf/2011-27461.pdf. Federal Register. 2011;76(212):67802-67990. Accessed May 19, 2015.

2. Kocot SL, White R, Katikaneni P, McClellan MB. A more complete picture of pioneer ACO results. The Brookings Institution website. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/10/09-pioneer-aco-results-mcclellan#recent_rr/. Published October 13, 2014. Accessed May 19, 2015.

Specialty and Operator Status Influence Electronic Health Record Use Variation

January 22nd 2026Operators demonstrated specialty-specific differences in electronic health record efficiency, timeliness, and after-hours use, highlighting how workflow and training shape documentation behaviors across medical disciplines.

Read More