- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

From Making Oncology Clinical Pathways Multidisciplinary, to Adding the Patient’s Voice

According to the final panel at Patient-Centered Oncology Care®, clinical pathways can create a new problem: if each payer tries to impose its own pathways, it’s an administrative and ethical nightmare.

The rise of decision support tools—clinical pathways—in oncology care can allow health systems to create standards for the use of expensive new therapies and identify those physicians who are not following guidelines.

For this reason, payers would seem to embrace pathways. But according to the final panel at Patient-Centered Oncology Care®, that can create a new problem: if each payer tries to impose its own pathways, it’s an administrative and ethical nightmare.

“Clinicians need a moral justification for using pathways—they have to believe that the choices on pathway are the right choices for a patient. So we cannot have different pathways for different payers,” said Kerin Adelson, MD, associate professor and chief quality officer, Smilow Cancer Hospital, Yale School of Medicine.

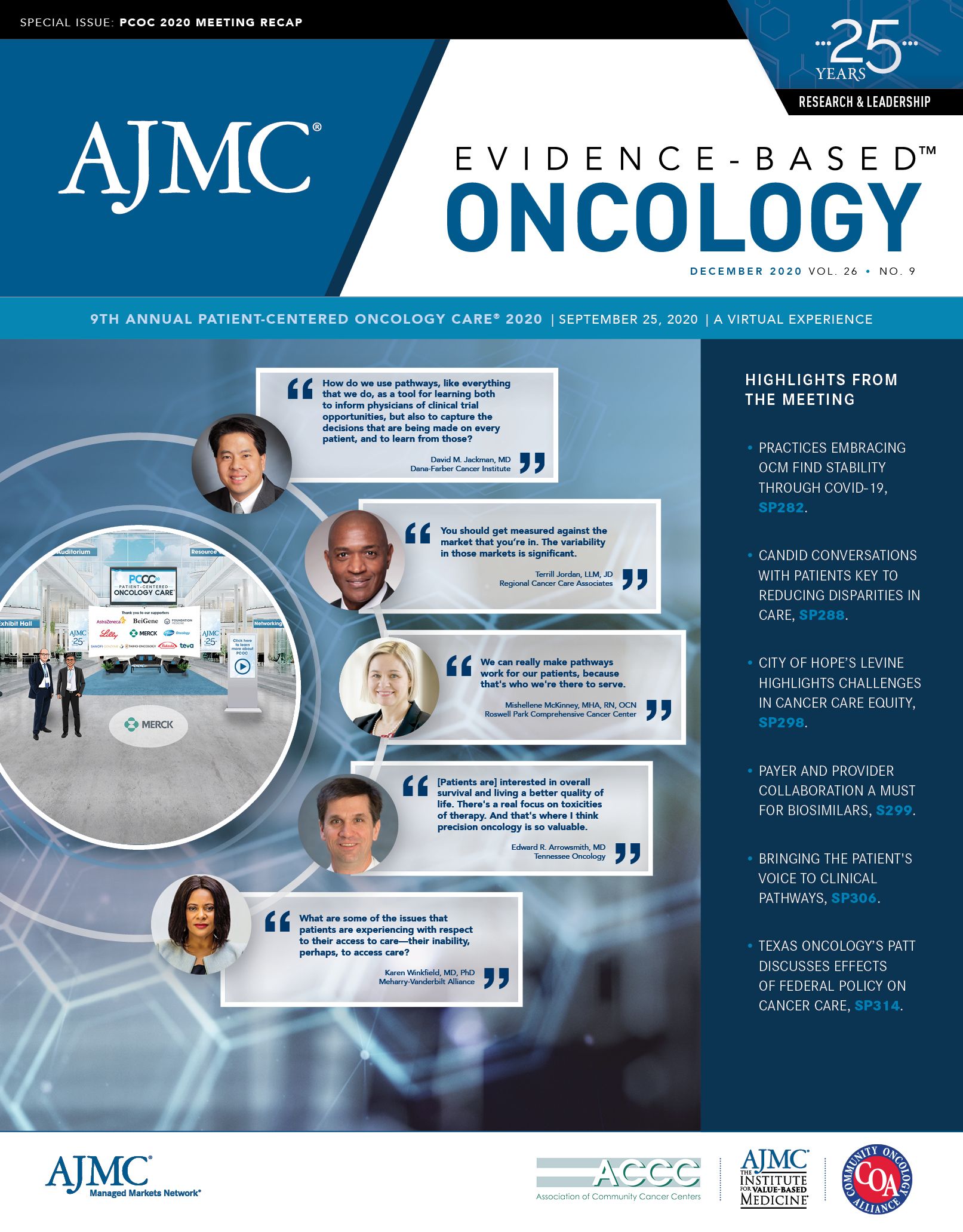

Led by meeting Cochair Joseph Alvarnas, MD, the panel featured Adelson; Karen Fields, MD, medical director, Clinical Pathways and Value Based Cancer Care, Moffitt Cancer Center; David M. Jackman, MD, medical director and clinical pathways physician, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Medical Oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; and Mishellene McKinney, MHA, RN, OCN, director, clinical pathways and implementation science, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Alvarnas first asked the panelists to explain the evolution of pathways at their institutions. Fields said Moffitt’s pathways program dates to 2009, and it has developed its own pathways, collaborating with Cerner on a platform based on the electronic health record (EHR) launched in 2015. Utilization has increased over time, she said, and physician involvement is key. “Our clinicians helped develop the pathways, and are very well aware of the standards that they’ve worked to create,” Fields said.

Moffitt’s development of multidisciplinary pathways, and a drive to get data from the EHR to evaluate practice patterns, have offered “ongoing opportunities for growth,” she said.

“There was actually no budget for implementing pathways,” when Adelson arrived at Yale, she said. “So that was on hold for a while until we started participating in the Oncology Care Model (OCM), which brought in additional revenue streams that would help justify clinical pathways.”

Adelson debated whether Yale should build its own pathways, as Moffitt had, or use a commercial pathway product. She opted for the latter, going with Via Oncology, which is now ClinicalPath. “I liked the idea of being part of a pathways process that had multi-institution consensus,” Adelson said. The product integrated with Epic, and she said she has been pleased with recent uptake. But as with Moffitt, there’s room for growth.

“The issue is that their pathways are really robust for some hematology, and for medical oncology, but they’re not multidisciplinary pathways,” she said.

But Adelson said pathways have been “instrumental” in ensuring that standards of care are the same at the academic medical center and in the community practices that make up the health system. Pathways also promote research by suggesting clinical trials.

Dana-Farber’s approach has been almost a hybrid of Moffitt and Yale. Jackman said the program dates to 2012 with an effort to codify best practices. And then, he said, came the questions: “How can we disseminate these best practices across our whole enterprise? And how do we use pathways, like everything that we do, as a tool for learning both to inform physicians of clinical trial opportunities, but also to capture the decisions that are being made on every patient, and to learn from those?”

Dana-Farber worked with Philips Healthcare, a commercial vendor, to develop pathways with customized content, created by its own faculty. Jackman’s job involves working with the faculty and Philips to ensure content is up to date and fits a workflow that is efficient and “thinks like a doc.”

Roswell Park’s pathways journey began in 2015, as a collaboration with Moffitt. McKinney said she and a colleague worked with Fields to learn the methodology, and then shared it with their physicians.

“We brought back the Moffitt pathways to our cancer center, and then modified them to reflect our local practice patterns,” McKinney said. “Those pathways are truly multidisciplinary—they incorporate medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and life care clinical trials.”

An important feature of the Moffitt pathways, she said, is the incorporation of drug costs. “That was very eye-opening to our medical oncologists when they were looking at 2 different options. They had no idea.”

Initially, the Moffitt pathways were a reference document, and as Roswell Park built its own pathways program, it sought commercial vendors so it could better measure uptake and concordance. Today, it also uses the ClinicalPath system.

Promoting Clinical Trials

Alvarnas said the 4 panelists and himself “represent 5 [National Cancer Institute]-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers, which may, given the research cores at each of these respective centers, increase the relative complexity of the clinical pathways.

“For lack of a better word,” he said, “academic centers often have a certain inertia associated with them. How have you navigated the challenge of capturing enough complexity regarding clinical trials, as well as getting your physicians to go on the journey?”

Said Fields, “Clinical trials have been a major component of our clinical pathways since the very beginning.” Their multidisciplinary nature has allowed the EHR to give clinicians information about clinical trials. Yes, there is maintenance involved, but the added features allow Moffitt to use pathways to measure quality, cost, and efficiencies, and quickly identify patients eligible for trials—at the point of care.

Adelson said following pathways and getting patients into clinical trials can require commitment and creativity from the research staff. Some of the best stories come from community oncologists, where a general oncologist could not possibly track every open trial, but a reminder from the pathway is the factor that gets their patient enrolled. And when patients are enrolled in trials, there are savings. “The drugs are being billed to the pharmaceutical company, but that really allows academic centers to be successful [under] value-based models,” she said.

Gaining the trust of pathway users is critical, Jackman said.

“It’s not just the users being able to see what trials are available and knowing when to send them in. It’s the converse as well, knowing when a trial isn’t available, and allowing folks in the satellites to retain their patients and be able to reassure them, ‘Look, I know what’s going on, and you know, at the campus in Boston, they don’t have a trial for you right now. But here’s what they would do.’”

Pathway developers and users learn from each other. “Learning happens in so many different ways with respect to trials,” he said. Pathway choices, or branching, can both recognize what’s currently available and anticipate what’s coming. For example, in lung cancer the Dana-Farber pathway has branches for EGFR and ALK mutations. “And we put a branch on for KRAS,” even though there’s not yet an FDA-approved agent. But branches can be built to accommodate clinical trials in emerging areas.

The Patient’s Voice

Alvarnas addressed a complaint from physicians that pathways don’t accommodate individual patients, and asked McKinney how this is handled at Roswell Park.

This is an area where there’s a need for more growth, she said. The ClinicalPath platform does “a really good job” at incorporating evidence-based preferences for patients. During the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, for example, the pathway incorporated subcutaneous therapies to reduce “chair time” from infusions.

But when it comes to patient wishes, the guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) are preferable, McKinney said. “One of the things that ASCO recommends is that patients are involved in the development of pathways. And I don’t know that there’s any commercial vendor that has started to do that.” If cancer centers are using a commercial platform, they should encourage patient involvement in development, but if they are developing internally, it’s on the institution to figure it out: “How we can incorporate our patients into that development and maintenance process, so that we’re getting their voice?”

Roswell Park built a patient education pathway and a young adult pathway, to recognize that this age group often has different outcomes and needs, such as fertility services. “They might be transitioning from Mom and Dad’s insurance and then going on to their own insurance plan,” McKinney said. “Once we get them through treatment, then there’s a whole other issue of survivorship, because they’ve got their whole life to live with potential comorbidities, potential for a secondary cancer. We can really make pathways work for our patients, because that’s who we’re there to serve.”

Adelson has research funding to develop a pathway that is a shared decision-making tool, with the physician seeing an evidence-based pathway. The patient can log in and see the evidence-based options, with differences by adverse effects (AEs). AEs are of varying importance to patients, she said.

“Right now, we are completely neglecting the voice and preferences of the patient, and this is actually an incredible opportunity to bring the doctor and patient together in a shared decision,” Adelson said. “The burden is on us as clinicians to do a better job with that.”

McKinney said patient-reported data could change pathways. If it turns out that only 5% to 7% of patients in the real world can tolerate a certain treatment, “maybe that really shouldn’t be the first choice on a clinical pathway.”

Talking About Cost

Adelson said CMS’ OCM incorporates a requirement of communicating with patients about their care plan, the one instance in which a payer requires this. For the most part, it doesn’t happen, and payers won’t cover shared decision making. Fields agreed, indicating that although payers say they want clinicians to incorporate patient goals, these things aren’t in contracts.

Adelson said: “When we talk about cost, we don’t do a good job about talking about ‘cost to whom?’ So there’s overall cost to society, which is the overall thing that a treatment costs in some ways, but it’s also how much productivity is lost from that member of society who may not be able to work. Then there’s cost to the payer.”

What the payer sees and what the patient “pays” are often not in alignment. Adelson said many breast cancer pathways put patients on paclitaxel weekly for 12 weeks, because it may not require supportive therapy. “But for a patient, that’s an extra 8 visits to the infusion center, it’s potentially an extra 1 to 2 months out of work. And it could mean hiring a babysitter and parking and all sorts of other things that may negatively impact their financial quality of life.”

Jackman agreed that many pathways are focused on drug costs and don’t look at the patient costs in the total cost of care. Dana-Farber has tried to collect this data to share with payers, but Jackman said the conversation is not “where we’d like it to be.”

Challenges with payers involve expectations that pathways are going to solve problems they are not designed to fix. McKinney and Adelson said pathways will never be designed for 100% concordance, because that would mean physicians are not taking individual patient needs into account. Roswell Park researched this issue, and found that 70% of cases handled off pathway were due to toxicity or a comorbidity.

Adelson said pathways are not the final answer to holding down drug costs—drug price reform is required. “Guideline-based treatment is extremely expensive when novel therapies are included,” she said. “If we’re looking at mechanisms to control costs, we’ve got to talk about pharmaceutical pricing.

In VERIFY, Rusfertide Spares Most Patients With PV a Phlebotomy for 32 Weeks, Improves QOL

June 3rd 2025Adding rusfertide to standard of care more than doubled the share of patients with polycythemia vera (PV) who did not meet criteria for a phlebotomy, according to data from the VERIFY trial.

Read More