- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

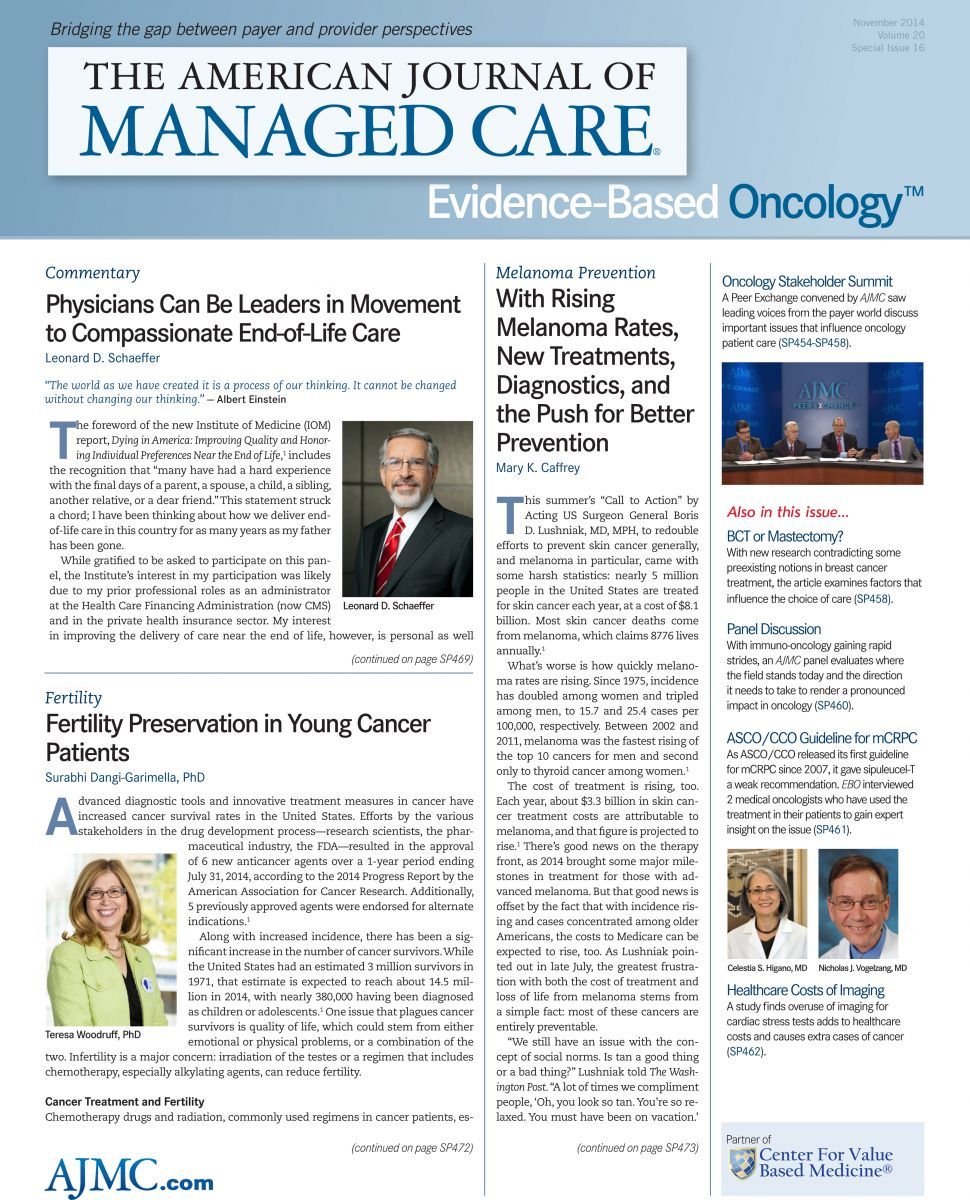

Physicians Can Be Leaders in Movement to Compassionate End-of-Life Care

“The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.” ― Albert Einstein

The foreword of the new Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life,1 includes the recognition that “many have had a hard experience with the final days of a parent, a spouse, a child, a sibling, another relative, or a dear friend.” This statement struck a chord; I have been thinking about how we deliver end-of-life care in this country for as many years as my father has been gone.

While gratified to be asked to participate on this panel, the Institute’s interest in my participation was likely due to my prior professional roles as an administrator at the Health Care Financing Administration (now CMS) and in the private health insurance sector. My interest in improving the delivery of care near the end of life, however, is personal as well as professional: it was the experience of my father, a man who had been in charge throughout his life, which led me to conclude that patients should never confront a healthcare system that doesn’t allow them to influence

decisions about how they die.

The IOM report captures well the interconnected challenges of a fragmented and inefficient healthcare system that leads seriously ill patients to transition frequently among different (and often inappropriate) care settings while families and caregivers deal with increasing responsibilities, costs, and emotional stress. The IOM report also identifies the role that reimbursement policy, especially Medicare, plays in perpetuating a model of acute and postacute care that encourages 911 calls, emergency department visits, hospitalization, nursing home stays, and futile care that people near the end of life often do not want.

Unfortunately, just changing the reimbursement system will not change the delivery of care near the end of life so that it honors patients’ preferences. The payer role, while critical to transitioning to a more patient-centered, family-oriented, evidence-based healthcare system, is not enough to achieve large-scale change. The transition must be supported by other stakeholders, especially the physician community.

Healthcare systems reflect cultural values, professional norms, and politics. This is why systemic change is difficult and requires sustained and effective leadership. Leadership is not a nebulous concept but the sine qua non for, as the Einstein quote says, changing our thinking. The strength of the IOM report and its recommendations is its inherent call for a change in our thinking at the societal, political, educational, systemic, and personal levels. As part of that call, the report describes a vision of what a system that delivers quality end-of-life care would look like, provides recommendations to serve as a roadmap to get there, and identifies the key change agents.

A properly designed healthcare system that meets the needs of patients near the end of life would effectively elicit and act on patient preferences and support the integration of medical and social services, which would be paid for by public and private insurance. The challenges to achieving this vision are twofold: first, it requires addressing the misalignment of incentives in a fee-for-service system that promotes maximizing the use of services that can jeopardize the quality of care and raise costs unnecessarily. Second, this vision requires financial support of social services, as well as clinical care, in helping produce better patient outcomes.

The IOM report does not rank in order the impact that different stakeholders can have on driving system change, but the combined weight of providers and payers (especially Medicare) can go far in influencing not just medical practice but cultural norms. Payers should redesign benefits and compensate providers fairly for initiating discussions about treatment preferences before patients face serious illness, for encouraging patients to participate in advance care planning, for integrating medical and social services, and for supporting the timely use of palliative and hospice care.

These provider behaviors, delivered at the point of service, would help establish a new culture of shared decision making that supports patients’ rights to choose care focused on relieving pain as well as life-extending treatments. Successful models of innovative programs both in state Medicaid programs and in the private sector, such as Sutter’s Advanced Illness Management Program2 and Aetna’s Compassionate Care Program,3 are proving this point. Evaluations of these programs show that knowledge of patients’ goals, team-based care, and access to community-based services improve quality of life while reducing healthcare costs.

IOM further recommends that reimbursement should be tied to proven standards of care that are “measurable, actionable and evidence-based.” The report calls for professional societies to take the lead in developing standards for clinician-patient communication and advanced care planning. Without active endorsement from professional leadership, traditional provider behavior could undermine progress in achieving patient-centered end-of-life care.

In addition to taking ownership of developing standards and metrics necessary for reimbursement, the physician community should play a leadership role in substantially improving the transfer of knowledge about palliative care to all clinicians caring for seriously ill people. We need to establish a culture of professionalism that accepts the importance of patients’ goals and values. To change cultural norms, we must improve the education and training of physicians and other professionals, across all practice settings, so that appropriate evidence-based care can be rendered consistent with patients’ preferences.

There is an urgency to improving healthcare at the end of life because of the increasing number of elderly Americans,4 the unsustainable cost growth in healthcare, and the growing public acceptance of the limits of modern medicine. The IOM report can serve as a road map, but only if transformational leadership emerges among key stakeholders, especially clinicians, specialty societies, and public and private payers. Moreover, changing public policy related to covered services, payment that realigns financial incentives, and blending Medicare and Medicaid funding streams for dual eligibles will likely require new legislation or regulation. Given the complexity of our political process, profound policy change will only happen if providers and payers advocate for the same vision.

Multiple surveys5,6 show that many physicians have completed advance directives and also say they would not choose aggressive care if they were terminally ill. The IOM report illuminates a way forward to give patients what physicians, themselves, would want when faced with advanced illness—a healthcare system that supports their right to participate in making decisions about how their lives will end.About the Author. Leonard D. Schaeffer is currently the Judge Robert Maclay Widney Chair at the University of Southern California. He was the founding Chairman & CEO of WellPoint, the nation’s largest health insurance company by membership, serving in those posts from 1992 through 2004 and remaining chairman through 2005. In 1986, Schaeffer was recruited as CEO of WellPoint’s

predecessor company, Blue Cross of California, when it was near bankruptcy. He managed the turnaround of Blue Cross and the IPO creating WellPoint. Previous roles include president and CEO of Group Health, Inc, of Minnesota, and administrator of the federal Health Care Financing Administration (now CMS), with responsibility for Medicare and Medicaid.References

1. Committee on approaching death: addressing key end-of-life issues. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=18748. Published September 17, 2014. Accessed October 29, 2014.

2. Advanced Illness Management (AIM). Sutter Health website. http://www.sutterhealth.org/quality/focus/advanced-illness-management.html. Accessed October 29, 2014.

3. Aetna Compassionate Care Program. Aetna website. http://www.aetna.com/individualsfamilies/member-plans-benefits/compassionatecare-program.html. Accessed October 29, 2014.

4. Administration on Aging. Projected future growth of the older population. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/future_growth/future_growth.aspx#age. Accessed October 29, 2014.

5. Helwick C. Advance directives: physician attitudes differ from actions. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/825592.Published May 22, 2014. Accessed October 29, 2014.

6. Gramelspacher GP, Zhou XH, Hanna MP, Tierney WM. Preferences of physicians and their patients for end-of-life care. Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):346-351.

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More