- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Developing Comparative Effectiveness Research in Oncology

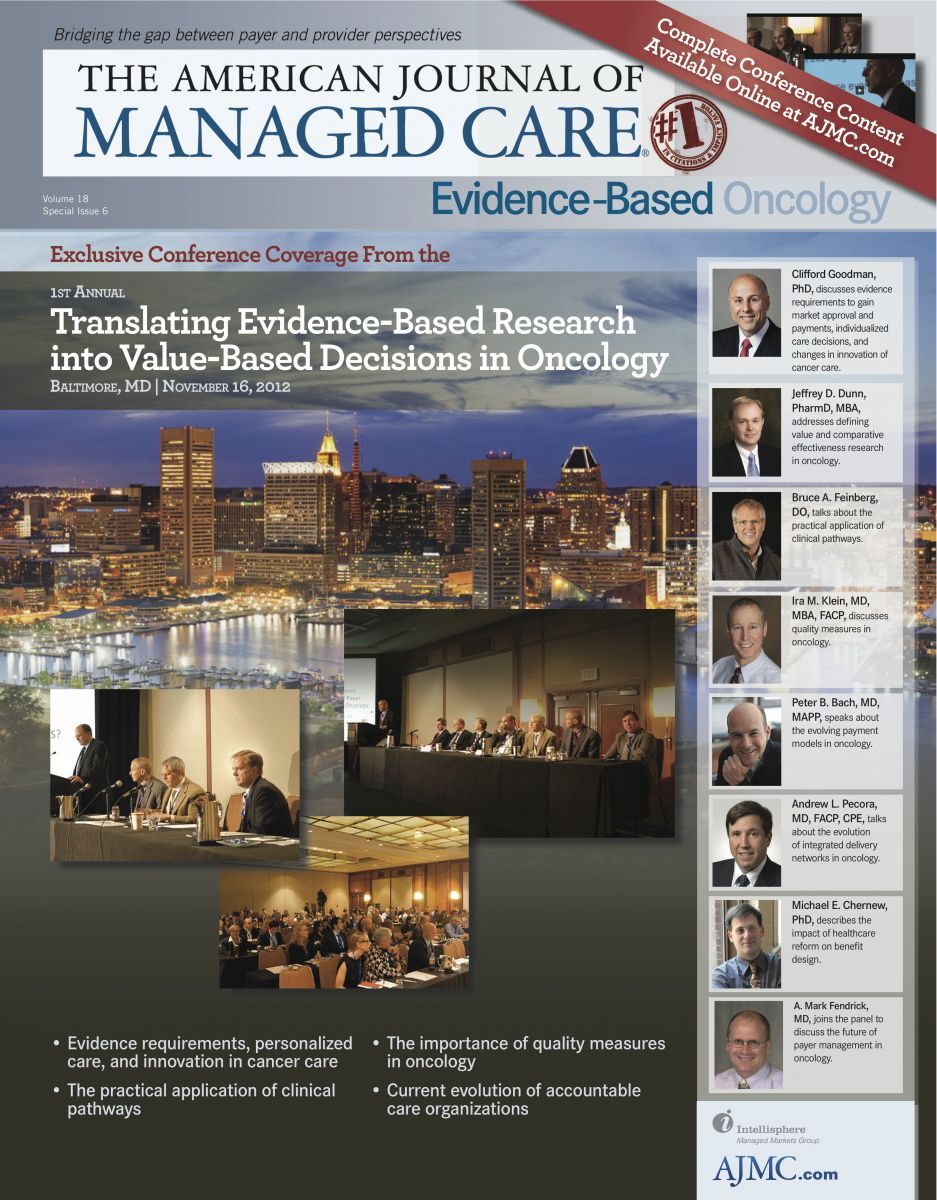

Figure

Cancer is extremely political and extremely emotional. That makes a discussion on the economics of cancer treatment tricky. Further, the cost and value of cancer therapies are not discussed properly. But they need to be discussed. Cancer treatments are expensive and the decisions that need to be addressed (end of life care, expensive side effects, quality of life, treatment efficacy) can significantly impact total costs ().

To introduce these issues, Jeffrey D. Dunn, PharmD, MBA, formulary and contract manager at SelectHealth, Inc, in Murray, Utah, gave a presentation entitled Defining Value in Cancer: Comparative Effectiveness Research in Oncology. Dr Dunn said that most people in oncology understand that the complexity of the treatment regimens, bioethics of certain treatment regimens, off-label use of drugs, the lack of consensus among guidelines, and patient education tend to be the topics of discussion, but there needs to be an honest discussion about the cost of care. Cancer is very expensive and the model for cancer care is difficult to fit into a traditional cost-management method. In some cases, cancer is an acute condition; in other cases, the cancer is similar to a chronic condition. And in some cases, it is less about cancer and more about end-of-life care. So, Dr Dunn asked, “Can oncology be considered a value-based disease state?”

According to him, the answer is as complex as the disease. The answer is also dependent on whom you ask. Both payers and clinicians believe costs can be reduced. Payers strongly believe that adoption of clinical pathways will reduce costs (80% of payers believe so) and improve cancer care (88% of payers believe so). Oncologists also believe that clinical pathways will reduce costs and improve care (61% and 60%, respectively).1 One way to improve cancer treatment and reduce costs may be the use of comparative effective research (CER).

CER

The purpose of CER is “to improve health outcomes by developing and disseminating evidence-based information to patients, clinicians, and other decision makers, responding to their expressed needs about which interventions are most effective for which patients under specific circumstances.” Historically, clinical pathways for breast, colorectal, and lung cancers have been in place for a number of years,2 and pathways for other cancers are being developed. To date, most pathway initiatives have been a collaborative effort between physicians and payers that have utilized the framework of guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CERs can provide great value, but some people confuse CER with restrictions, rationing, or cost-containment issues. Dr Dunn stated that CER is intended to provide real-world evidence on the most cost-effective therapies in an effort to improve outcomes and reduce costs.

CER Is Local

Good CER requires the engagement of local oncologists. Dr Dunn said that regional variations make it imperative for local oncologists to be involved. Also, the engagement of local oncologists helps develop better working arrangements between oncologists and payers that can allow both parties to be more effective. With that being said, there are a few disadvantages to tweaking the guidelines to create CER that is more regional. Dr Dunn noted that evidence may need to be “massaged.” If a local doctor performs a treatment successfully but it is not in the guidelines, it can be tricky to address that issue. As such, it becomes more difficult to defend certain requests where the data are not black and white, but in a gray area. And that gray area is common in oncology. It has been estimated that one-half to three-fourths of all cancer drugs are used off label.3 Dr Dunn stated that there are so many new drugs and new treatment ideas being developed that it is difficult for compendia to keep up. That is why local oncologists’ input is needed; however, it is also why it can be a struggle to balance what physicians know or think is better in comparison with the guidelines or regulatory agencies.

Dr Dunn said that CER evidence should be based on outcomes (not surrogates), be clinically meaningful, have outcomes that are patient centered, and include costs. He also noted that the CER should be translated into language that can be understood by physicians, payers, and patients. If done properly, the use of CER as a decision-support tool should:

• Reduce variability in outcomes

• Reduce variability in costs

• Invest in patients’ health and improve health outcomes

• Reduce wasteful spending by reducing toxicities

The Problem With Cancer Evidence

According to Dr Dunn, randomized controlled comparative studies are rare in oncology. In most cases, “We end up relying on cohort studies, population studies, predictive studies, and modeling. So, this is not ideal. And even when we do have randomized controlled trials in oncology, a lot of these are short term and use surrogate efficacy outcomes because they are not long enough or powerful enough to show benefits in survival. They are often limited in sample size and they are often not powered to show statistical improvement over [the] existing standard of care.”

CER and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research

Dr Dunn said there is a growing trend to include patients (and payers) in the study design using patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR), in which both parties have input into the study’s comparators and outcomes. Equally important, both parties may have a better idea of the risks and benefits of a treatment compared with parties that traditionally designed studies. He also noted that PCOR is a new idea to oncology; as a result, it is limited. However, Dr Dunn indicated that the studies have a realworld component to them that is often missing in more traditional trials.

Estimating Cost of Oncology Treatment

Cost is very difficult to estimate in cancer. This is due to many factors, including treatment regimens that are constantly changing, combination therapy, and new algorithms, all of which can extend the life of patients but create new indirect costs. That is why increasing use of PCOR to obtain real-world data is important. PCOR can also help identify subgroups of treatment responders.

Dr Dunn also noted that PCOR does have its limitations and barriers. Data can be inconsistent or unreliable. Other barriers to success include poor communication that impedes constructive feedback, provider pushback, and incentives that may be misaligned. The key for success is for all parties to be in constant communication to make sure that the data being studied will have value for future clinical pathways.

Concluding Remarks

Dr Dunn concluded his presentation by reiterating that efficacy and costs need to be addressed when developing CER, and that all parties need to be involved. However, oncology treatment is very complicated. He used a simple example of 3 oncology drugs with sharp differences in daily versus monthly costs. It is up to the physician, payer, and patient to determine which treatment is best, and that is not an easy task.

1. The Zitter Group. The Managed Care Oncology Index. Winter 2011. http://www.zitter.com/OncologyIndex. html. Accessed November 21, 2012.

2. Danielson E, Demartino J, Mullen JA. Managed care & medical oncology: the focus is on value. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(suppl 7):S28-S37.

3. “Off-label” indications for oncology drug use and drug compendia: history and current status. J Oncol Pract. 2005;1(3):102-105.

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More