- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

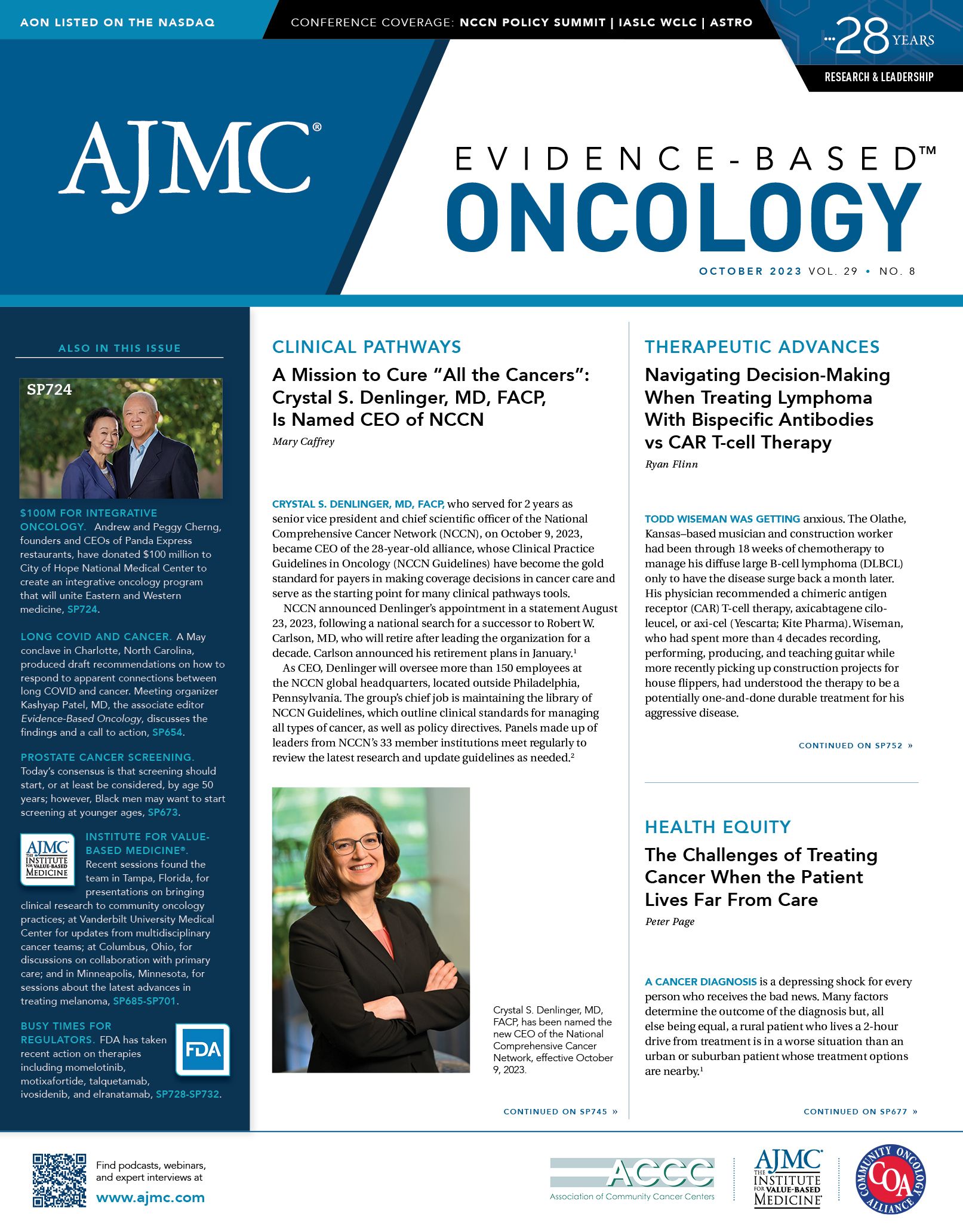

Coverage in Health Equity: October 2023

Health equity coverage appearing in the October 2023 issue of Evidence-Based Oncology.

Expert Panel Addresses Prostate Cancer Misconceptions, Importance of Screening

Although common, prostate cancer remains misunderstood, and Prostate Cancer Awareness Month in September served as an important reminder to consider prostate health and learn about the facts, myths, risks, and treatments available. With advanced prostate cancer incidence on the rise, educating the public is increasingly important, as experts from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Urological Association emphasized in a panel discussion hosted by Newswise on September 11, 2023.

The panel included James Eastham, MD, FACS, governor of the ACS and chief of urology service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; Kara Watts, MD, associate professor of urology at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York; and Kevin Koo, MD, MPH, associate professor of urology at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minnesota.

Misconception: There Are Clear Signs and Symptoms

Eastham

After a brief overview of the prostate and its functions by Eastham, Watts opened the discussion by highlighting that early-stage prostate cancer is not accompanied by many symptoms and is easily overlooked.

Watts

“It can get confused with benign enlargement of the prostate, which happens over time—it’s very common, especially as male patients are to be over [age] 50 years…. And so, it can be confused sometimes with

Koo

some of the urinary symptoms that come with enlargement of the prostate such as changes in your urinary flow, slow stream, hesitancy or pushing to urinate, or having to urinate more frequently,” Watts said.

Prostate cancer is most manageable in early stages when it may be asymptomatic. Because the warning signs are vague and often go unnoticed, men should feel encouraged to initiate conversations with their clinicians. Identifying risk and treatment paths early is potentially lifesaving. “I think it’s important for men…to think about prostate cancer screening exactly for the reasons that my colleague Dr Watts has mentioned,” Koo remarked.

The consensus among urologists is that screening is beneficial to begin—or at least consider—at age 50 years; however, other factors may place individuals at higher risk for developing prostate cancer. Black men are the most at-risk population; genetic components also affect one’s vulnerability.

Societal Issues Contribute to Inequities, Reluctance

Each expert weighed in on potential challenges men of all backgrounds face when it comes to prostate health. Eastham noted the hesitancy of minority groups to seek health care, whether due to past events causing mistrust of clinicians and the health system, or financial barriers limiting their access to services and resources.

Koo echoed these points and, in a similar thread, mentioned how geographical hurdles can physically hinder access to forms of care. He also commented on how misunderstood and intimate prostate concerns can be. Both factors may make these conversations difficult or uncomfortable to have with a physician.

“I’d like to also mention that there are broader policy and societal factors at play here, too,” Koo continued. “It wasn’t too long ago, about 10 to 15 years ago, when the advice about prostate cancer screening really took a dramatic turn and health professionals were being advised that prostate cancer screening might do more harm than good. We know now that some of those recommendations were misguided or based on misinterpretations of the best evidence we had at the time.”

Eastham described old screening processes that detected elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels that seemingly necessitated prostate biopsies. Many low-risk prostate cancers were identified, and this led to the overtreatment of many individuals who possibly never needed it. He mentioned alternative routes that are now available because “it’s not simply you have PSA, you need a biopsy, and if you have any cancer, we need to treat it.”

Watts largely agreed with her colleagues; however, her experience has given her a unique perspective when it comes to thinking through the multifactorial nature of disparities affecting underserved populations. In the Bronx, where she works, the population enduring the greatest mortality ratio is that of non-Hispanic White men: “So while African American Black men do have a higher risk of more aggressive prostate cancer, it is not those men who are being disproportionately affected here ... the point I want to make here is you have to look at what’s happening around you and not assume based on big numbers and studies that we have that that’s exactly what’s playing out in your area around you.”

Whether an individual is affected by any of these factors, the panelists emphasized the value of connecting with a primary care physician, stating that these conversations will open doors to essential education and treatment paths for patients and clinicians to assess their health needs.

“I like to encourage patients in my clinic to think about their urological health the same way they might think about their car’s health,” Koo added. “You wouldn’t necessarily want to wait until there’s a major transmission problem before going to seek some care.” He believes regular checkups provide a great opportunity to raise concerns about any issues, no matter how uncomfortable, because urologists encourage it and “it’s easiest to engage in these conversations when we are all advocates for men’s urological health.”

Patient Awareness and Education Are Crucial

Prostate biopsies are associated with negative adverse effects and, as Koo mentioned, previous controversies about the efficacy of biopsies can lead some patients to “shy away from the conversation about prostate cancer screening.”

Two beneficial innovations in prostate cancer treatment include active surveillance and focal therapy. Eastham detailed how “active surveillance is a management strategy. It’s not benign neglect.” This approach involves intermittent check-ins that usually analyze PSA levels to reassess a patient’s risk. This treatment is applied for those identified with low-risk prostate cancers to monitor any progression that could inform next steps.

Focal therapy is when treatment is solely applied to the most aggressive or critical area of a patient’s prostate cancer, Watts explained. She noted how this method minimizes adverse effects and is especially beneficial because it preserves the rest of the organ. There are many options within this therapy as well, including cryotherapy, needle-based therapy, irreversible electroporation, focused energy ablation with heat, and photodynamic therapy.

Eastham particularly believes in earlier PSA testing between ages 40 and 50 years. Getting a baseline risk assessment, he commented, can help indicate the future course of your treatment, whether you will need treatment, or if you are at risk.

Even if screening leads to a diagnosis, Watts and Koo encouraged patients to “take a deep breath.” No decisions on treatment need to be made right away, and taking the time to get informed by trusted officials and clinicians will be a tremendous tool for managing care moving forward.

Genetic Alterations Are Seen in Hispanic Men With Prostate Cancer

Findings from a recently published study revealed differences in gene alterations occurring in Hispanic White men with prostate cancer (PCa) compared with non-Hispanic White men. This research addresses an important demographic gap in the literature on Hispanic men with PCa.

In the United States, PCa is the most prevalent form of cancer affecting Hispanic and Latino men, as well as the No. 1 cause of cancer death for men in Latin American countries. Despite this, research on the pervasiveness and implications of altered DNA in Hispanic men—and their associations with PCa—is still relatively understudied.

For this study, researchers analyzed patient samples of primary and metastatic adenocarcinomas from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Men with targeted next-generation sequencing genomic profiles were identified, and a gene was considered altered if it exhibited at least 1 reported point mutation, structural variant, or copy number alteration. Hispanic White and non-Hispanic White categories were also created after analyzing available ethnicity and primary race data from a plethora of contributing institutions.

Data from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center included 1412 samples of primary tumors (n = 78 Hispanic White; n = 1334 non-Hispanic White) and 818 samples of metastatic tumors (n = 40 Hispanic White; n = 778 non-Hispanic White).

Results from primary tumor analysis evaluated 465 genes and revealed significant differences in 10 genes between the 2 groups. Non-Hispanic White men were less likely to have alterations than Hispanic men in the following genes:

In primary adenocarcinomas, 2 gene alterations were less common in non-Hispanic White men than Hispanic men. They were TMPRSS2 (31.86% vs. 51.28%, odds ratio [OR] = 0.44 (0.27-0.72), P = .0007); and ERG (25.34% vs. 42.31%), OR = 0.46 (0.28-0.76), P = 0.002. In metastatic tumors, the KRAS and CCNE1 alterations were less prevalent in non-Hispanic White men. Data for KRAS were (1.03% vs. 7.50%), OR = 0.13 [0.03, 0.78] p = 0.014, and for CCNE1, (1.29% vs. 10.00%), OR = 0.12 (0.03, 0.54), P = .003.

No significant differences were found in actionable alterations and androgen receptor mutations between the groups. Due to the lack of clinical characteristics and genetic ancestry in this dataset, correlation with these could not be explored. The total number of actionable mutations and total mutations in DNA repair genes was higher in metastatic samples than in primary tumors. However, there were no significant differences in prevalence between the 2 cohort groups.

The authors noted that their small cohort size made it difficult to fully assess race- and ethnicity-specific tumor diversity. Despite this limitation, they emphasized the importance of their research as the first to investigate the genomic patterns of Hispanic men with metastatic and primary PCa tumors.

Although racial and ethnic differences cannot fully explain patient outcomes, the researchers stressed how meaningful future studies can be for understanding the extent to which genetics influence PCa behavior. They also wrote that they hope their study sparks interest in further research on non-White and non-European populations and on the implications that gene-targeting therapies, prostate-specific antigen levels, cancer grade, and stage have on assessing potential risks for certain patients.

Reference

Arenas-Gallo C, Rhodes S, Garcia JA, et al. Prostate cancer genetic alterations in Hispanic men. Prostate. 2023;83(13):1263-1269. doi:10.1002/pros.24586

SPOTLIGHT: Joseph Mikhael, MD, MEd, FRCPC, FACP, on Strategies to Increase Diversity in Multiple Myeloma Trials

Mikhael

Evidence-Based Oncology: What efforts are being made to ensure diversity and representation of underrepresented groups in clinical trials for multiple myeloma studies?

MIKHAEL: This is a great disparity in multiple myeloma, where now, in the United States, we estimate that approximately 20% of all patients with myeloma are of African American descent like myself. And yet representation in clinical trials has historically been somewhere between 5% to 8% and arguably even less in pivotal trials that have led to drug approval.

This is a grave problem, because it’s not only a lack of representation in those trials but also a lack of understanding of the efficacy and toxicity of these agents in different patients. We’re already starting to see in immunotherapies [that] there can be differences in the rates of cytokine release syndrome and neurological toxicities in patients of African descent and in Hispanic patients, for example.

So this is a huge problem, and I think there isn’t going to be a simple and rapid solution, but many solutions are being proposed that include addressing the hierarchical system of systemic racism, of access to health care, of trust within the system. But [we] also [have] very pragmatic answers of ensuring that clinical trials have a diversity officer, that the materials are designed to be able to be read by and supported by a diverse population, [and] that we as health care providers are trained in understanding culturally sensitive care so that we cannot be a barrier but be a facilitator of the best care [for] our patients, which very often includes clinical trials.

These are just some of the highlighted issues that I think will help solve the problem as we try to develop a system that has much greater community engagement. I think that has been a missing piece in our health care systems: We’ve been so focused on explicit health care that we haven’t looked at the greater interest of engaging our communities at large, which will build that trust [and] which will build that confidence to be able to work together more.

SPOTLIGHT: Sigrun Hallmeyer, MD, Says Precision Medicine Must Become More Efficient

Hallmeyer

In this interview with Evidence-Based Oncology (EBO), Sigrun Hallmeyer, MD, medical oncologist with Advocate Health Care, addresses logistical holdups in precision medicine that may be preventing all patients who need this care from being able to access it. Among the top issues are inappropriate care and wasteful health care spend.

EBO: Can you discuss potential policy priorities to increase equitable access to health care?

HALLMEYER: Curing cancer is, of course, the headline—that’s what we’re all wanting to do. But where we sort of fail and have an issue is the logistics of how you translate that. Precision medicine certainly plays a huge role in that, and health equity plays a huge role in that because access to care is one big problem that we have in this country. Another big problem, which I think is equally large, is that we have a lot of waste within our system. I would say probably a good one-third of our health care dollar is stuck in our system because we duplicate care or we have care that is inappropriate, too late or early, wrong, etc. With all that, we need to become better in becoming efficient and automated.

The [appropriate discussion of precision medicine or personalized care should not be a boutique situation that is only offered to wealthy, highly educated patients who have the resources to come to the oncologist and ask for it or conversely for patients who are seen in higher-level centers of care where the physicians are familiar with the precision medicine approach and have the [appropriate] logistical background, where you have all the pieces in place where such tests can actually lead to an impact on their care.

And so what I think would probably be the very best sort of societal approach to equity in care would be that we need to find a way to reflex these type of things. Very simply put, if you have, say, a lung cancer diagnosis, it shouldn’t matter if you [receive a diagnosis] in South Chicago, [Illinois], or at [The University of Texas] MD Anderson [Cancer Center] in Houston or at [Memorial] Sloan Kettering [Cancer Center] in New York, [New York]. Your specimen should be reflexively tested for targetable mutations, and the patient and physician should be equally enabled to use that information to define a targeted or precision medicine approach to their therapy.

Regional Disparities Remain in Breast Reconstruction for Patients With Breast Cancer

Regional variations in the utilization, complication rate, and cost of breast reconstruction for patients with breast cancer exist; however, there does not seem to be regional variation in implicit bias that is associated with these differences, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open. The investigators sought to understand whether differences in breast reconstruction rates for White patients and patients of other racial and ethnic groups were a result of implicit racial bias by region.

Although there is evidence that breast reconstruction improves quality of life after breast cancer, the procedure is underutilized following mastectomy, the authors explained. “Understanding drivers of disparities, such as biases among physicians, may serve as the basis for more equitable care,” they wrote.

General structural issues in the US health care system are known to result in disparities in access to care, but the study found that implicit racial bias by region did not correlate with these differences.

The study used data from the National Inpatient Sample from 2009 to 2019 on 52,115 adult women with a diagnosis of or a genetic predisposition for breast cancer. To measure implicit bias, they used the Implicit Association Test (IAT) data from Project Implicit. The investigators linked the 2 databases to evaluate whether implicit bias was associated with any regional variations identified in breast reconstruction utilization rates.

The analysis included 38,487 White patients and 13,628 patients of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. The majority had private insurance (76%), although White patients were more likely to be privately insured than underrepresented racial and ethnic groups (79% vs 69%). Most patients received implant-based reconstruction (72%).

The ratio of White to underrepresented racial and ethnic group utilization for breast reconstruction was 1.03 for all regions. The ratio was highest for the East South Central division (2.17) and lowest for the West South Central division (0.75).

Although there were differences in the complication ratio by region, the ratio was highest for the East South Central division (1.73) and lowest for the West South Central division (0.73). “Spearman rank correlation between the [weighted average] IAT score and breast reconstruction complication rate ratio for all divisions was 0.1 (P = .81), indicating annual complication rates did not correlate with changes in IAT at the division level,” the authors noted.

In an unadjusted analysis, White patients had a lower mean cost of care compared with patients of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups ($24,934 vs $25,256). However, cost was higher for White patients in the New England division. Again, Spearman rank correlation indicated no correlation with IAT changes at the division level.

Among the limitations listed by the authors is the accuracy of the data in the database and the lack of information on potential confounding factors for the implicit bias data. In addition, more detailed categorization of the patients beyond just White or underrepresented race and ethnicity could better help guide policy, they noted.

According to the authors, the overall findings show “implicit racial bias by region did not correlate with differences in breast reconstruction utilization or complication rates between White patients and patients [of underrepresented] racial and ethnic groups.”

Because of general structural issues in the US health care system that result in disparities in access to care, policies targeting physicians may not be enough to combat these disparities, they wrote.

“Despite evidence that some of these disparities are decreasing, efforts to reduce the observed inequities should remain a national priority,” the authors concluded. “Efforts from individual institutions and national surgical organizations are needed to provide culturally competent, evidence-based care to individuals of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

Reference

Nasser JS, Fahmy JN, Song Y, Wang L, Chung KC. Regional implicit racial bias and rates of breast reconstruction, complications, and cost among US patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2325487. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25487