- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

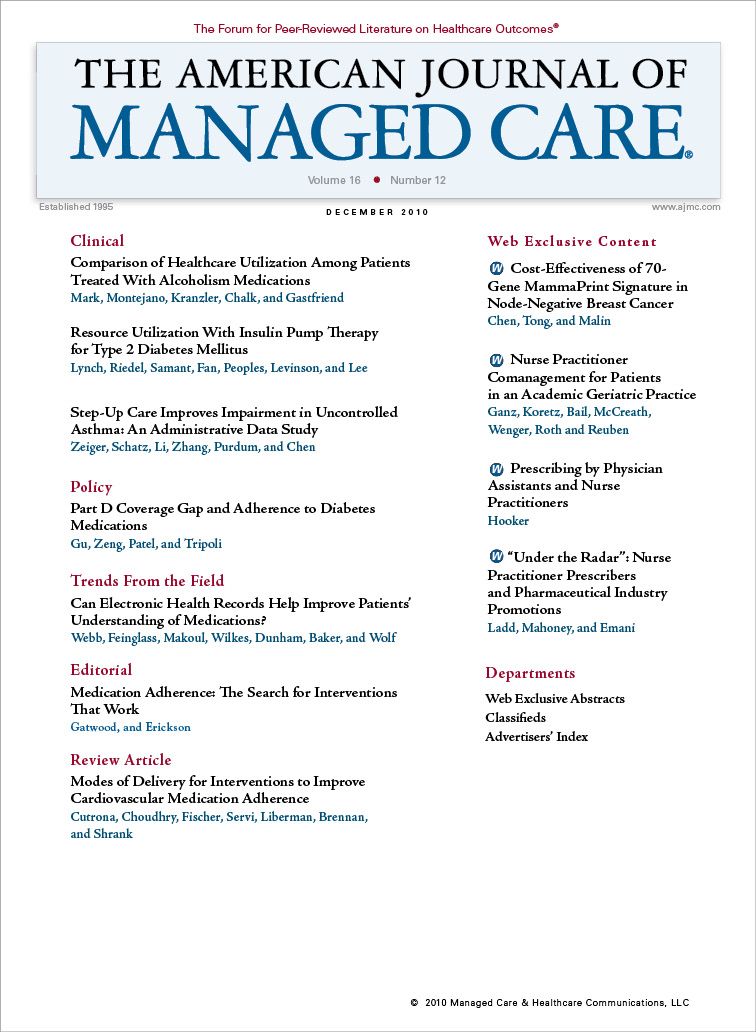

Prescribing by Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners

We have insufficient understanding of what influences our prescribing behavior, particularly with respect to pharmaceutical marketing strategies.

The legal constraints on prescribing are different for each country but usually involve a physician giving guidance to a patient, preparing something, or sending the patient to the pharmacist (chemist) to obtain a preparation. It is a rite of passage when a physician in training first learns how and what to prescribe. Furthermore, the sociological act of giving a prescription to a patient brings the visit to a conclusion. All prescribers know that this activity involves both the art and the science of medicine and often involves meeting patient expectations. In many ways it defines the clinician. The patient usually expects something as a result of the visit and the clinician is in the position to provide something, usually a prescription.

Public policy for healthcare delivery (including delivery of medication) is focused on safety. There is a relationship between the Food and Drug Administration, which provides federal oversight of drug safety, and the states, which authorize who can prescribe. This authorization has evolved to include many more players than physicians. In 1969, Colorado passed enabling legislation permitting physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) to prescribe under the authority of a supervising physician. Four decades later almost all states and most federal jurisdictions permit some form of prescribing by PAs and NPs.

Although this policy evolution occurred over the objections of some physician organizations about expanded prescription authority, the reality is that this change is codified. Since the turn of the century, new doctors have not known what it is like to work without PAs and NPs who prescribe. In spite of this expansion from one domain (eg, doctors, dentists, veterinarians) to another (eg, PAs, NPs, psychologists, optometrists, midwives, anesthetists, pharmacists), some misconceptions remain. In the United States, outpatient-prescribing authority is handled by the individual states. If controlled substance prescribing is requested, the Drug Enforcement Agency issues authorization. Inpatient prescribing is usually in the form of an order; the PA/NP acts as the agent for the attending physician. Hospital bylaws control most of this inpatient activity. Also, federal reservations and jurisdictions (eg, the Veterans Health Administration) are not subject to the various constraints imposed by the states.

The specific medications that doctors, PAs, and NPs prescribe is a bit more muddied and unfortunately, many unsubstantiated claims are made. The tendency is for professional societies to count heads and multiply by some rate of prescriptions per day. This method is problematic because not all providers prescribe (eg, pathologists, radiologists). Pharmaceutical firms and the data-collecting agencies of these firms closely guard prescription-marketing numbers. Furthermore, what is written is not necessarily what is dispensed, so prescriber recall and pharmacy administrative files do not always correspond. This discrepancy is no trivial matter, evidenced by the fact that the United States spent $234.1 billion on prescription drugs in 2008—more than double what was spent less than a decade before in 1999. According to recent research, 48 % of Americans of all ages took at least 1 prescription drug in 2008.1 It is known that PAs and NPs tend to prescribe in a manner similar to physicians in similar settings.2 These observations were drawn from the National Center for Health Statistics’ ongoing series on outpatient clinical activity.

In this issue of the Journal, Ladd and colleagues bring into focus another observation: like physicians, NPs are influenced by pharmaceutical marketing strategies and tend to respond in the same way that physicians do.3 That is not surprising because the principles of marketing are well-tested areas of behavioral science and cultural anthropology. Marketing is the commercial process involved in promoting and selling a product or service, and those who do it are skilled at their task. However, many clinicians naively believe that they are immune to marketing influences.4

There is insufficient understanding regarding what influences the prescribing behavior of American doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. But with the wealth of data accessible from national databases, this information should be within the reach of those who ask the right questions. For example, do all members of a primary care team prescribe in the same way when different variables are controlled? Is there a regression to the mean in prescribing trends among medical groups? Although there is some discomfort in knowing that well-educated and experienced doctors, NPs, and PAs may prescribe in the interest of pharmaceutical companies, proactive inquiry can lead to a better understanding of why we prescribe the way we do. Uncorking the metadata of pharmacy benefits in federal integrated health systems and comparing prescribing trends by setting, types of patients, types of providers, and types of illnesses would be a start. Both quantitative and qualitative studies about PA and NP prescribing behavior are necessary. This is a new area for cost-containment strategies and, if prescribers are malleable to pharmaceutical marketing strategies, perhaps they are flexible to cost-containment strategies as well. The increasing use of electronic health records affords an opportunity to learn more about this cornerstone of patient-centered care.

In the end, the United States has an ever-widening sphere of prescribers and the pharmaceutical industry has an everwidening interest in marketing to such prescribers. Knowing something about how many and what kinds of drugs are prescribed, and who receives them, seems fundamental to good medical management.

Author Affiliation: From the Department of Veterans Affairs, Dallas, TX.

Funding Source: Dr Hooker reports no external funding for this work.

Author Disclosure: Dr Hooker reports no relationship or financial interest with any entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article.

Authorship Information: Concept and design; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and administrative, technical, or logistic support.

Address correspondence to: Roderick S. Hooker, PhD, The Lewin Group, 3130 Fairview Park Dr #800, Falls Church, VA 22042. E-mail: rodhooker@ msn.com.

1. Gu Q, Dillon CF, Burt VL. Prescription drug use continues to increase: U.S. prescription drug data for 2007-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010; (42):1-8.

2. Hooker RS, Cipher DJ. Physician assistant and nurse practitioner prescribing: 1997-2002. J. Rural Health. 2005;21(4):355-360.

3. Ladd E, Mahoney DF, Emani S. Under the radar: nurse practitioner prescribers and pharmaceutical industry promotions. Am J Manag Care. 2010; 16(12):358-362.

4. Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, Johnson M, Schumm P, Lindau ST. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008; 300(24):2867-2878.

HEDIS Glycemic Goal Achieved Using Control-IQ Technology

December 22nd 2025A greater proportion of patients with type 1 diabetes who used automated insulin delivery systems vs multiple daily injections achieved the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) glycemic measure.

Read More

Linking Data to Determine Risk for 30-Day Readmissions in Dementia

December 22nd 2025This study found that certain characteristics in linked electronic health record data across episodes of care can help identify patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias at high risk of 30-day readmissions.

Read More

Performance of 2-Stage Health-Related Social Needs Screening Using Area-Level Measures

December 19th 2025Limiting health-related social needs screening to lower-income areas would reduce screening burdens; however, this study found a 2-stage screening approach based on geography to be suboptimal.

Read More

Impact of Medicaid Institution for Mental Diseases Exclusion on Serious Mental Illness Outcomes

December 17th 2025Medicaid’s Institution for Mental Diseases (IMD) rule bars federal funding for psychiatric facilities with more than 16 beds, but findings indicate that state waivers allowing treatment of serious mental illness in IMDs do not increase overall psychiatric hospitalizations.

Read More