- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

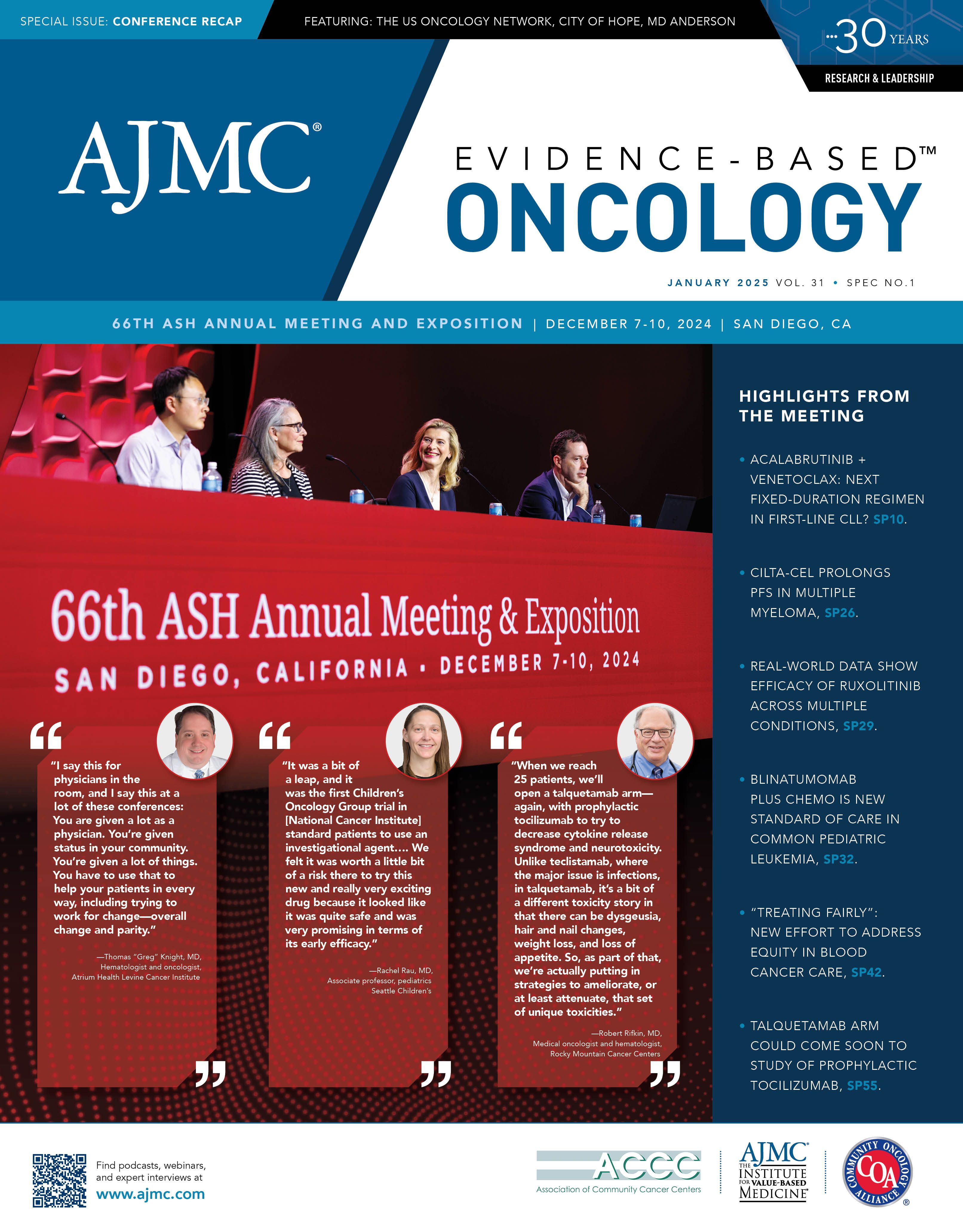

Quality Session Launches “Treating Fairly,” Addresses Equity in Care, Access, Data Collection

The American Society of Hematology is launching a health equity effort, "Treating Fairly," which was discussed at the quality symposium at the 66th Annual Meeting & Exposition.

For 11 years, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) was an avid participant in “Choosing Wisely,” a campaign by the ABIM Foundation that eventually reached 80 specialty societies with a mission to weed out tests or treatments that drove up costs or caused unnecessary risk despite a lack of evidence.

“Choosing Wisely” ended in 2023, and now ASH is creating a successor campaign, “Treating Fairly,” which will use a similar process to identify areas where care in hematology is not delivered equitably, with the goal of correcting such practices.

Adam Cuker, MD, MS, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and clinical director of the Penn Blood Disorders Center, announced the new campaign as he kicked off the symposium, “Treating Fairly: The Role of Quality Improvement in Combating Health Care Disparities,” which took place December 7, 2024, during the 66th ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition in San Diego, California.

Speakers outlined how Michigan is using better data to drive interventions; how Ontario, Canada, had improved standards for treating iron deficiency in women; and how one health system created a process to financial toxicity, improving access to cancer care. Angela Weyand, MD, of the University of Michigan, cochaired the session with Cuker.

Quality Improvement Through MSHIELD

Melissa Creary, PhD, MPH | Image credit: University of Michigan

Melissa Creary, PhD, MPH, is an associate professor of health management and policy and global public health at the University of Michigan. Her research interests include antiracism and health equity, as well as sickle cell disease as a lens to investigate health equity and health policy. Creary discussed the Michigan Social Health Interventions to Eliminate Disparities (MSHIELD) program, which she described as a collaborative quality initiative within the hospital system at the University of Michigan that impacts the entire state.

The program, she said, is among 23 Collaborative Quality Initiatives (CQIs) in Michigan that are physician and hospital led that seek to improve patient safety and outcomes; some CQIs are disease focused, on areas such as diabetes, anticoagulation, lung, or back care; MSHIELD, Creary said, is focused on health equity—it is designed to achieve whole health for all by integrating social and clinical care, using data to drive health equity, and “fostering a culture of antiracism.”

“The big part here is that we have funding and support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM),” Creary said. Rather than take a top-down approach, this is an externally funded health equity–centered quality initiative driven from the bottom up.

The CQI process started 25 years ago, she said, and “is made up of physician organizations and hospitals around the state that are led by local clinicians who set the quality improvement agenda.” The process relies on “granular data collection, analysis, and transparency” to drive practice improvement. Creary explained that early CQIs focused on specialty care and then moved into primary care; today, this process is moving into what she calls “cross-cutting consultation,” involving community stakeholders.

“We think that centering health equity is the next phase of quality improvement,” Creary said. “It is necessary in order to achieve the outcomes that we're looking for.”

Recent steps include the creation of a pay-for-performance (P4P) task force to create a consistent process for addressing equity through specific incentives. BCBSM backs this.

The CQI developed recommendations that align with antiracism values and its core pillars of (1) data collection that allows race/ethnicity stratification, (2) social needs screening and linkages, and (3) building the capacity and culture of health equity in quality improvement. These are:

- For Pillar 1, work with hospitals for standardized health equity coding across hospital dashboards

- For Pillar 2, develop optimal modes of submitting social needs data to statewide platforms, in line with federal requirements

- For Pillar 3, develop opportunities for hospital leaders to take part in health equity–focused trainings within existing structures

Creary spoke at length about how these goals aligned with emerging federal requirements and how this process could serve to reduce inconsistency in reporting of race-based data. Health systems and providers are increasingly called upon to address health equity but may be given little guidance on how to carry this out. Consider the work that went into the recommendation for Pillar 1:

“Race-based data is kind of fraught when we think about the reasons why we might collect them. We also know that if we don't collect them, we're not able to understand the needs of the population based on race and ethnicity and among Michigan hospitals,” she said. “There's currently variability in race and ethnicity data collection practices, which can lead to difficulty identifying and addressing disparities across the hospital system.”

Creary noted that despite requirements to collect such data, “there's no standard guidance to hospitals on how to collect and submit race and ethnicity data in the Blue Cross Blue Shield P4P program or otherwise. What we're interested in doing is identifying areas of focus for equity-focused quality improvement goals and activities, and to measure the effectiveness of quality improvement.”

The work of the CQI drove a recommendation to create standardization in reporting. “That standardization piece is really key,” she said, as it would lead to consistency across dashboards for equity-focused quality improvement.

Creary noted that the Joint Commission has called for hospital leaders to address health care disparities as a quality and safety priority—to build a “culture of health equity.” MSHIELD is developing training modules to help leaders meet this goal, “although we are being very careful of how we think about the terminologies of antiracism moving forward.”

She said, “I do think that, in general, people across the system understand that health equity is the way to move toward better health outcomes, and they want to have better relationships with the communities that they serve.”

Creating a “New Normal” to Manage Disparities in Iron Deficiency

Michelle Sholzberg, MDCM, MSc, FRCPC | Image credit: St. Michael's

Michelle Sholzberg, MDCM, MSc, FRCPC, director for the University of Toronto Division of Hematology and an associate professor at St. Michael’s Hospital, is an expert on coagulation and bleeding disorders in women. Her presentation, “Raise the Bar: Combatting Disparities in the Recognition and Management of Iron Deficiency,” outlined her years-long effort in Ontario to redefine what constitutes a low ferritin threshold, thus including more women in the definition of nonanemic iron deficiency and explaining symptoms of fatigue, maternal morbidity, inability to concentrate, and reduced productivity.

Many of these women had heavy bleeding during periods; although their iron levels might appear “normal,” their symptoms and daily lived experience were not, she said.

Calling iron deficiency “the original pandemic,” Sholzberg said the condition affects huge numbers of women and children—roughly 40% of women in high-income countries and possibly 100% in low- and middle-income countries. “Iron deficiency anemia affects 2 billion people annually,” she said. “It is the leading cause of years lived with disability in women worldwide. It is important because it's associated with severe maternal morbidity, mortality, and enduring neurocognitive abnormalities in children born to mothers who have anemia. The number one cause of maternal anemia is iron deficiency.”

Yet this “structurally sanctioned” problem exists largely because definitions of what constitutions “low iron” are set far too low—at levels that were not based on the best available evidence. And so, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a group of medical experts—from hematologists to laboratory technicians in hepatopathology and biochemistry—began working on “Raise the Bar.”

The group grew from the University of Toronto to include academics from across Canada, to those in the US, the United Kingdom, and Australia, she said. “We knew that we needed to address the ferritin lower limits of normal in laboratories to signal abnormal results when we thought they should be signaled based on the best available evidence.” In effect, they needed to define the new normal.

And it would not be easy.

“An abnormal flag is a known driver of clinician behavioral change,” Sholzberg said. “We also knew that a serum ferritin is the most reliable and feasible diagnostic test to screen for iron deficiency. But we asked ourselves, what are the evidence-based serum ferritin thresholds to mark iron deficiency? And are those thresholds different in adult patients vs pediatric patients?”

Going in, the level for unacceptably low iron deficiency was 15 µg/mL for adults. After examining evidence, the group determined that although a serum ferritin level below 30 µg/mL is the accepted level for mild cases of iron deficiency, it had been shown since 1992 that levels below 50 µg/mL might be an even better indicator—as Sholzberg explained, that is when gastrointestinal absorption of iron returns to baseline, along with other key biomarkers.

Judy Truong, MSc, completed a systematic review of 62 studies to determine the normal lower limit of ferritin. “She found that these studies included apparently healthy individuals, but many did not assess for clinical history nor laboratory parameters of iron deficiency, nor its risk factors,” Sholzberg said.

The most common tests for iron deficiency used worldwide failed to exclude patients with iron deficiency risk factors when developing their assays, and thus Truong concluded that “the ferritin reference intervals are at high risk of bias.” Despite guidelines that say iron is key for a child’s brain development during pregnancy, the test kits were designed to be more concerned about false positives than false negatives.

The Ontario group next surveyed practitioners on what ferritin levels they felt were appropriate. They proposed raising the unacceptably low level from 15 to 30 µg/mL for adults and to 20 µg/mL for a pediatric cases; levels of 30 to 50 µg/mL would indicate a probable iron deficiency. Of the 165 responses, 93% of them were physicians, including 53% hematologists.

“[For] a majority of respondents, 80% said that the threshold of below 30 [µg/mL] for adults and less than 20 [µg/mL] for pediatrics, that it sounded good, that they were not concerned about it—and those who did express concern or reported concern indicated that they thought that the thresholds for both populations were too low. They thought that this was going to lead to underdiagnosis," Truong explained. “They thought that we should be adopting a threshold of closer to 50. The respondents also indicated a need for additional education. Most importantly, there were no responses indicating concern about incorrect or over diagnosis of iron deficiency.”

The group knew this survey was needed if the clinical limit to “abnormal” would be raised by 20%. “So, the people have spoken—they’re more worried about false negatives.” With backing from the Ontario Medical Association, the Ontario Association of Medical Laboratories, and the 2 largest commercial laboratories in Canada, Ontario updated guidelines for iron deficiency; Truong published her review in Lancet Hematology.1 As of September 2024, the new guidelines took effect.2

“It’s an example of structural change. It's an example of reframing our concept of normal,” Sholzberg said. She was candid about the work needed to make the change—companies had to update reagent kits; the Ontario team that pushed for the change undertook a massive education campaign.

Later, in response to a question, she described some of the backlash she received when presenting the need for higher threshold for iron deficiency—one speaker accused her of “weaponizing” social determinants of health. With a coauthor, Sholzberg described the health equity issues at stake in JAMA Network Open.3

“We ask, would the world ever allow for the passive acceptance of laboratory screening definitions that came with the slightest risk of diminished opportunity to address a correctable condition associated with White male mortality, morbidity, and decreased productivity? It is frankly unimaginable.”3

Testing companies that had much at stake backed the effort, she noted. “The absurdly high prevalence of iron deficiency means that this is very risky business, as I've described. These are companies, and they knew that they were going to increase the proportion of abnormal flags by 20% and they were really worried about it.”

“If you ask us how many complaints they've had to date, because that's what they were really worried about, zero,” Sholzberg said. “There are a million people that I need to thank, but most importantly, my patients and all members have raised the bar.”

Creating a Model to Address Financial Toxicity

Thomas "Greg" Knight, MD | Image credit: Atrium Health

Thomas “Greg” Knight, MD, gave the final presentation, “Cancer and Poverty: Mitigating the Impact of Financial Toxicity in Patients With Hematologic Malignancies,” which delivered on its promise—moving beyond descriptions of what happens when patients can’t afford cancer drugs and offering a solution.

Knight, a hematologist/oncologist at Atrium Health Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, North Carolina, described a pair of innovative solutions he’s spearheaded.

He briefly reviewed well-known evidence on financial toxicity, such as work led by Scott Ramsey, MD, that showed patients with cancer who experienced bankruptcy were 80% more likely to die.4 Knight noted that drugs to treat hematologic malignancies are among the most expensive in cancer care—and the costs of care don’t stop with the medication. Transportation, loss of income, just keeping a food over one’s head after a job loss all add up—and, he said, many of these costs are entirely predictable.

One of Knight’s goals is to create a more efficient tool to discover patients’ financial challenges early, before a patient simply doesn’t show for an appointment. “Where we are now is a retroactive process. Basically, we discover these issues after they've already occurred, patients having financial stress, and we are just trying to fix things,” he said. “There are a couple studies heading this way,” which would use a 2-question screening instrument.

An effective method, which has plenty of evidence, is financial navigation. Knight used his 2-question screening tool in the leukemia clinic and recruited pro bono financial planners from Charlotte’s banking community. “They brought a level of expertise that we don't have. We are really good at thinking about things like Medicaid information, co-pays, things like that. We don't think about how to budget, how to teach people to budget.”

Unfortunately, this project was interrupted by COVID-19. But it did give Knight some insight into its success. Although he acknowledged this test does not meet the level of scientific evidence, he compared a group of patients who worked with the volunteer planners with a matched population that could not once the pandemic hit. Among high-risk patients—those with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes—the risk of death was 56% less likely.

“We do have now a randomized trial in the AML population that's supposed to be opening in Dallas in the next few weeks,” he said.

A System-Level Intervention

What Knight has created today at Atrium Health is built on the concept of the tumor board—putting everyone involved in a patient’s care around the table—except in this case the focus is on the patient’s financial well-being.

“We started this in 2019,” Knight said. “We actually had the chief financial officer there with members of their staff, financial counselors, social workers, nurse, navigators, and then pharmacy and multitudes of others. The conference continues to grow. What I will say is the only thing that we said when we started this was that we wanted to have decision makers in the room. The one thing we said was we did not want to go to 15 people after the conference. We want to be able to make decisions immediately.”

All kinds of problems are solved—from payer issues, to underinsurance, to coding issues, to inadequate internal procedures. Knight offered an example of a 30-year-old with AML whose disease had cost him his job—along with his employer-sponsored insurance. “This patient’s in a crisis,” Knight said. “So, we get him COBRA insurance and we get him food assistance, we get him gas cards, we get them all the different things that will set them on a path to be able to get treatment for their cancer and hopefully not have a huge bill at the end that will ruin the rest of their life.”

“But there's another level to doing this, in kind of a systematic way, which is, as a group realize, we could have figured this out beforehand.”

What’s needed, Knight said, are frameworks to identify these patients before things become a crisis—so that health systems can be proactive. “This model has had a widespread impact nationally….I get calls probably once every couple of weeks from institutions that are interested in this model.”

The next step, he said, is helping patients figure out how to cover cost-sharing that comes with a treatment plan. “We have provided co-pay assistance to over 6000 patients with a total dollar value of over $6 million, as well as provided free drugs to over 10,000 patients, saving patients greater than $200 million.”

Knight fears for what is to come on the policy front. “We need to reform the payer structure,” he said. Medicaid expansion took a long time to come to North Carolina, and it took advocacy.

“We know that things will probably be different going forward with some of these issues, but what I would say is that we have to continue to work for change, and we have to continue to be the advocate for our patients in every way,” Knight said. “I say this for physicians in the room, and I say this at a lot of these conferences: You are given a lot as a physician. You're given status in your community. You're given a lot of things. You have to use that to help your patients in every way, including trying to work for change—overall change and parity.”

“But in the meantime, we’ve got to work really hard at the local level,” he said, “to do everything we possibly can to try to help our patients.”

References

1. Truong J, Naveed K, Beriault D, Lightfoot D, Fralick M, Sholzberg M. The origin of ferritin reference intervals: a systematic review. Lancet Haematol. 2024;11(7):e530-e539. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(24)00103-0.

2. Harrison L. Ontario's new iron deficiency guidelines may change lives: doctors. CBC News. September 9, 2024. Accessed December 15, 2024. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/iron-deficiency-bloodwork-testing-ontario-1.7314795

3. Tang GH, Sholzberg M. The definition of iron deficiency—an issue of health equity. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2413928. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.13928

4. Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early morality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980-986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620.