- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Patients With Cancer Face Major Financial Roadblocks, Not All Concerning Out-of-Pocket Costs

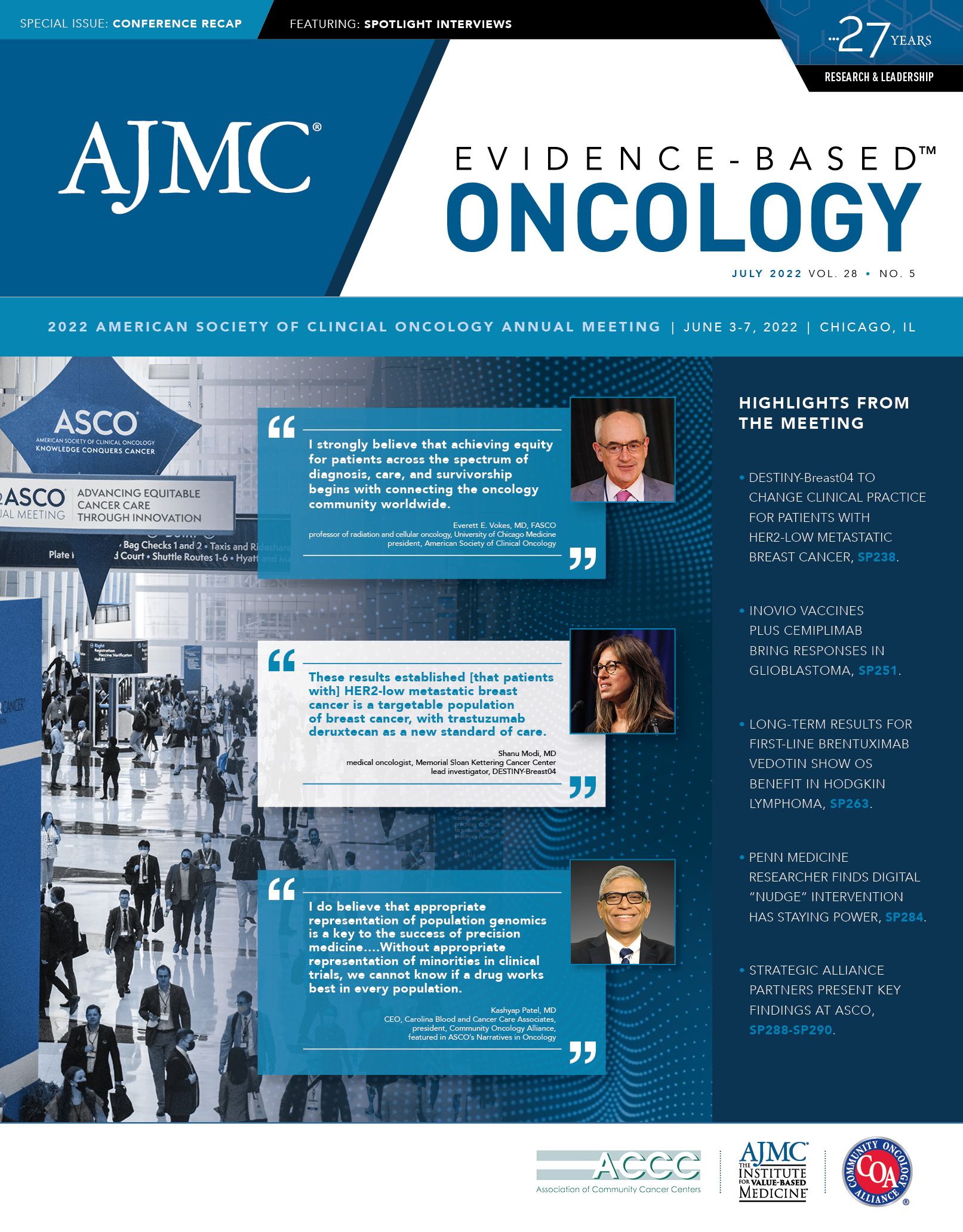

Abstracts presented at this year's American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual meeting detailed the financial hardships many patients with cancer face, including those related to high-deductible health plans and clinical trial participation.

Two presentations at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) addressed different facets of the financial burden imposed on patients with diagnosed cancers. Both were part of a session on health services research and quality improvement.

Financial Burden From HDHPs1

In his presentation, Nicolas K. Trad, a fourth-year medical student at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a research fellow in the Department of Population Medicine, discussed findings on the potential impact of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) on delaying metastatic cancer diagnoses.

In 2006, Deductible Relief Day—the date when most people have met their annual medical deductible and insurance kicks in—typically occurred by the end of February. As recently as 2019, this milestone had been pushed back almost 3 months to mid-May— indicating it took patients 3 additional months of out-of-pocket spending to reach their deductible. Concurrent with this trend, Trad and colleagues’ research on workers enrolled in HDHPs shows a consistent uptick in enrollment between 2006 and 2019, to the point that HDHPs now cover more than half of US workers.

“Due to increased out-of-pocket obligations, patients may postpone presenting for concerning symptoms or diagnostic testing, leading to delayed diagnosis,” lead author Trad and his team wrote. “We therefore assessed the impacts of HDHPs on the timing of metastatic cancer detection,” knowing that previous research already shows use of HDHPs has led to breast cancer–related delays in biopsy, imaging, diagnosis, and chemotherapy initiation.

HDHPs were originally intended to control health care costs, when first introduced in 2003. Instead, they have led to a decrease in health care utilization due to patients’ increasing out-of-pocket spend to reach their annual deductibles, even with the plans’ goals of “incentivizing” patients to shop around for lower prices and avoid unnecessary care. As a result, patients may be more likely to delay diagnostic visits and receive a later-stage cancer diagnosis, Trad noted.

The participants in this study were aged from 18 to 64 years and had no cancer history. They were matched 1:5 to a study group (n = 345,401; employers mandated the switch to an HDHP from a low-deductible health plan [LDHP]) and a control group (n = 1,654,775; employers only offered LDHPs), with 2003-2017 data gleaned from a national commercial and Medicare Advantage database. Matching criteria included demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, poverty level, region), morbidity as measured by Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) score, and baseline medical and pharmacy costs. For this analysis, HDHPs had annual deductibles of at least $1000, whereas those of LDHPs were $500 or less. The baseline period was 1-year LDHP enrollment for all participants, who were followed for 13.5 years.

During a mean follow-up period of 38 months, 1668 metastatic cancer diagnoses were made. Whereas no difference in time to metastatic diagnosis was seen in the baseline period (HR, 0.96; P = .67), participants were shown to have a longer time to first metastatic diagnosis if they had to switch from an LDHP to an HDHP (HR, 0.88; P = .01). This was “indicative of delayed detection relative to the control group,” the authors wrote, for a total of 4.6 months compared with the control group with continuous enrollment in LDHPs.

These delayed diagnoses could further translate into delayed palliative care and limited therapeutic options, Trad pointed out, all because of the exposure to high cost-sharing.

“The policy relevance of these findings are that they highlight a great need for innovative insurance models that don’t deter patients from seeking care,” Trad concluded, “as well as plans that align rather than contradict the goal of improving population-level survival from cancer.”

Areas of focus for future research include how HDHPs affect quality of life and treatment use among this patient population.

Medicaid Expansion’s Impact on Clinical Trial Participation2

In the second presentation, Joseph M. Unger, PhD, MS, an associate professor in the Cancer Prevention Program, Public Health Sciences Division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, and a SWOG Cancer Research Network biostatistician, discussed how passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion influenced enrollment and participation in cancer clinical trials.2

Unger and colleagues’ study of 51,751 participants, which accounted for peaks and troughs of cancer clinical trial enrollment, compared total patients using Medicaid coverage who enrolled before and after initial implementation of the ACA. Unger and his team found that the ACA improved clinical trial access for patients using Medicaid coverage between 2014 and 2015.

Overall, by 2020, following the act’s expansion, the number of patients using Medicaid in clinical trials increased to 17.8% compared with 6.9% before the expansion. When investigators compared states that expanded coverage vs those that did not, the odds of patients using Medicaid in clinical trials was nearly 4 times greater in states with expanded coverage.

Unger and his team used data from the SWOG Cancer Research Network. All patients aged 18 to 64 years who were enrolled in treatment trials between April 1, 1992, and February 28, 2020, were included in the analysis. Data on patients who enrolled in trials starting in March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic was just beginning, were excluded because “this period was considered not to be representative of previously demonstrated temporal associations between unemployment and use of Medicaid insurance.” Adjustments were made for the monthly unemployment rate using Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

“Our analysis is premised on the idea that the proportion of patients using Medicaid for their medical insurance generally parallels national economic trends,” Unger stated, “especially the unemployment rate.” He highlighted the fact that trends in Medicaid use among trial participants typically follow unemployment trends—for example, coverage increases as unemployment increases, as it did during the 2007-2009 recession—by about 1 year’s lag time, but that this was reversed following implementation of the ACA.

The study coauthors saw an overall 19% greater annual chance of clinical trial enrollment among patients using Medicaid coverage following the act’s expansion (odds ratio [OR], 1.19; 95% CI, 1.11-1.28; P < .001), as the number of those with Medicaid coverage increased by just over 37% pre- to post-ACA implementation, from 8.6% to 11.8%. However, the number of those actually using the coverage is highly variable over time, Unger pointed out, a finding considered statistically significant. The findings between male and female patients were starkly different: female patients were 26% (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.13-1.38; P < .001) more likely to use Medicaid coverage in clinical trials, whereas male patients were only 8% (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.96-1.22; P = .21) more likely.

Among their primarily female (67.3%) population, younger than 50 years (40.4), 62.6% were living in the 32 states that expanded Medicaid coverage between 2014 and 2015. Most participants were neither Black (91.6%) nor Hispanic (95.5%).

Among the policy implications of these findings are that improved access to clinical trials for Medicaid patients means that those who are socioeconomically vulnerable have greater access to the newest treatments, Unger emphasized.

“Improved access to clinical trials for more vulnerable patients is critical for improving confidence that trial findings apply to the general cancer population as well,” he concluded. “And one might reasonably assume from these findings that the recently enacted [Clinical] Treatment Act, which mandates that state-level Medicaid programs cover routine care across clinical trials for Medicaid patients may, in fact, improve access to clinical trials for socioeconomically underserved populations.”

References

1. Trad NK, Hassett MJ, Zhang F, Wharam JF. Impact of high-deductible health plans on delays in metastatic cancer diagnosis. Abstract presented at: 2022 ASCO Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 2022; Chicago, IL. Abstract 6503. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://meetings.asco.org/2022-asco-annual-meeting/14377?presentation=206347#206347

2. Unger JM, Xiao H, Vaidya R, Hershman DL. The Medicaid expansion of the Affordable Care Act and participation of patients with Medicaid in cancer clinical trials. Abstract presented at: 2022 ASCO Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 2022; Chicago, IL. Abstract 6505. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://meetings.asco.org/2022-asco-annual-meeting/14377?presentation=206536#206536