- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Communication Disparities Contribute to Care Disparities

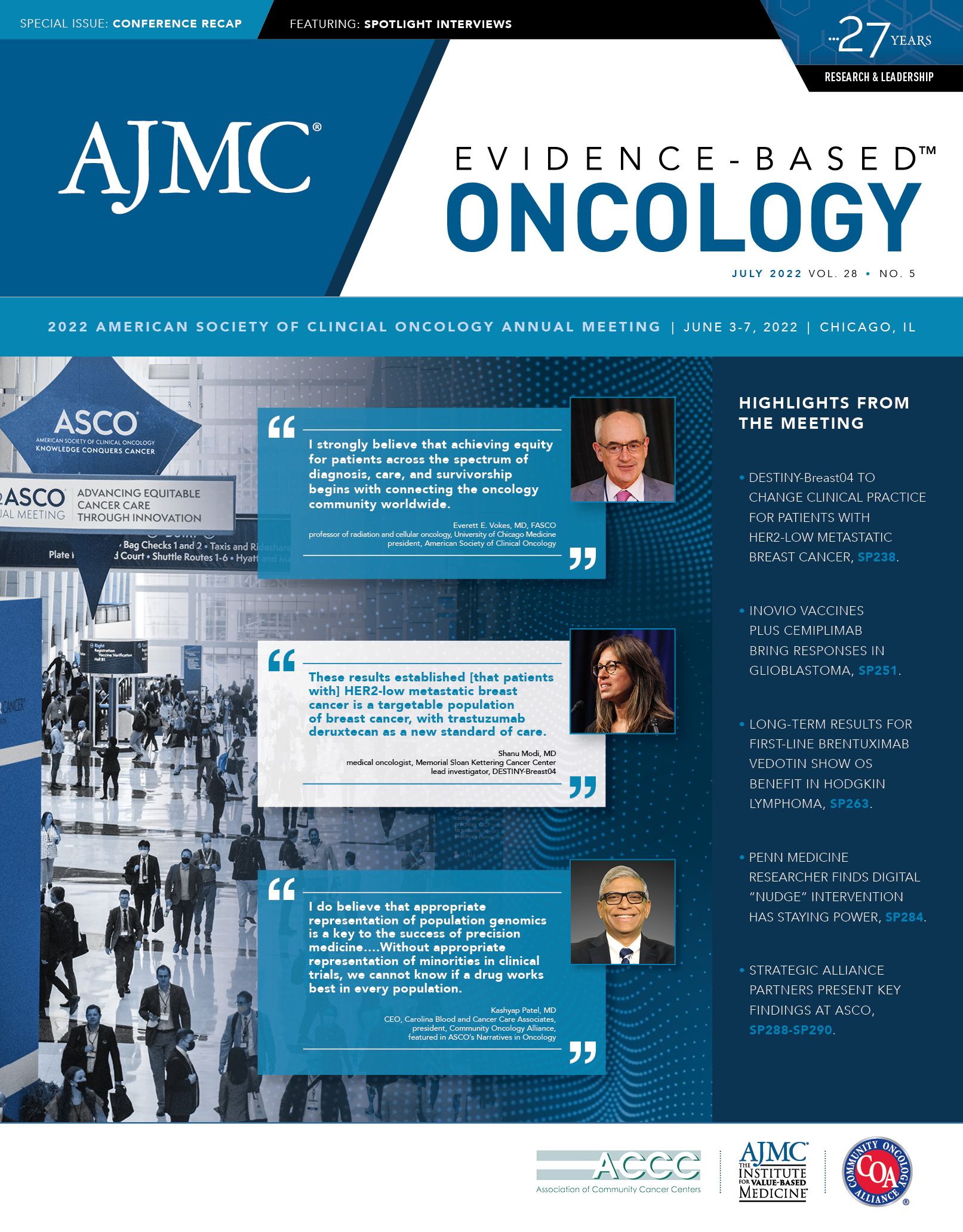

There are disparities in end-of-life (EOL) care decisions and serious illness communication between non-Hispanic White patients and minority patients, echoing the need to increase health care equity, according to a speaker at the 2022 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in June.

End-of-Life Communication1

“We probably have the most data when it comes to satisfaction with care, communication, support, pain management, hospitalization, and other utilization and advance care planning,” noted Cardinale B. Smith, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Division of Hematology/Medical Oncology and Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York. Kicking off her presentation, “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in End-of-Life Care,” she started on a positive note: The data are in and we can learn from them.

Unfortunately, even among minority patients—which for her discussion comprised those who identify as African American or Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander—how much is known about the many facets of EOL care varies. Whereas most information on care satisfaction, communication, emotional/spiritual support, pain management, hospitalization at EOL, and advance care planning comes from African American/Black patients, the least is known about Asian/Pacific Islander patients.

Comparing what is known on outcomes among non-Hispanic White patients compared with minority patients, Smith cited research showing that although Black patients were more likely to want aggressive, curative care at EOL, they were less likely to receive the EOL care they wanted and more likely to receive noncurative but intensive EOL treatment. Advance directives are also less common among these patients, and they have less favorable beliefs about hospice care.

Reasons for these disparities between patient wants and provided care fall into 5 categories, Smith noted, which were:

- patient preferences,

- distrust in the medical system,

- implicit bias leading to ineffective communication,

religious coping, and - lack of advance care planning (both documentation and discussion).

Black patients are more likely to report problems with physician communication, receiving inadequate information, and lack of familial support vs White patients, respectively: 41.6% vs 27.9%, 63.3% vs 41.0%, and 57.55% vs 37.3%.

“We’re not communicating with these populations in a way that is effective for them and in a way that is leading and contributing to what outcomes happen to them at EOL,” she said. “There’s clearly fundamentally something happening in this communication approach that is not helping them get to where they want to be. Unless we start to move toward narrowing this gap, it will only continue to increase.”

In fact, in the outpatient cancer setting, Black patients are more likely to report communication as poor and less informative and to give EOL care a lower quality rating. This translates into fewer Black patients with cancer being enrolled in hospice care compared with the general Black patient population.

Findings from a communications study at Icahn School of Medicine, which enrolled both patients and physicians, continued this disparities trend.

According to those results, physicians spent 5 fewer minutes with minority patients than they did with White patients when discussing their overall care, as well as during visits that did not focus on disease progression. The largest average difference of 7.5 minutes, favoring more communication time with White patients, was seen when both patient groups rated their general oncology care as low quality.

“I think we’ve been hoping for magic for a while, but magic does not work,” Smith concluded. “Change is necessary for our patients. They are our priority and why we’re here.”

Serious Illness Communication2

A study by a team of investigators at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and the Duke Cancer Institute looked at interactions between oncologists and patients with advanced cancers. The results showed that clinicians were found to spend considerably less time in communication with their non-Hispanic Black patients compared with their non-Hispanic White and Hispanic patients—and these findings echoed previous research from the group.

Outcomes were compared between solid-tumor oncologists who did and did not receive a coaching intervention. Baseline recordings and postimaging patient encounters were analyzed for coaching intervention effectiveness and use of serious communication skills (for this study, open-ended questions, reflective statements, empathic responses, empathic statements, “sorry” statements, and elicitation of questions), respectively. Patient participation and global codes of oncologist communication also were evaluated. Fifty-six recordings were included in the final analysis.

“Racial/ethnic disparities in serious illness communication exist between patients with cancer and their oncologists,” the authors wrote. “Our prior work has shown that goals of care discussions are 3 minutes shorter with racial/ethnic minority patients. In this study, we sought to compare oncologist’s use of serious illness communication skills, patient participatory behavior, and overall communication quality.”

Among the participants in the final analysis, 45% were female, 57% were older than 65 years, 36% were non-Hispanic Black, 20% were Hispanic, and 41% were non-Hispanic White. Forty-nine percent were older than 65 years.

Overall, less than 20% of oncologists’ communication was considered to be empathetic, even though encounter quality for flow, concerns addressed, attention, warmth, and respect were consistent among the patient groups. However, downward trends were seen when comparing outcomes among the patient groups.

The fewest reflective statements were used with non-Hispanic Black patients vs non-Hispanic White patients and Hispanic patients: 0.3 statements per encounter vs 1.1 (P = .02). And using a 5-point Likert scale, the lowest ratings for addressing patient concerns and for warmth toward their patients (P = .04 for both) were given to oncologists who met with non-Hispanic Black patients. These clinicians received 3.1 and 2.9 ratings, respectively, compared with 3.4 and 3.3 for oncologists when they met with Hispanic patients and 3.8 for both when meeting with non-Hispanic White patients.

Additional study findings show the following:

- Clinicians took advantage of fewer empathetic opportunities with non-Hispanic Black patients (2.2) and Hispanic patients (2.3) vs non-Hispanic White patients (2.6). They issued fewer “I’m sorry” statements: 0.2 and 0.0 vs 0.3.

- Far fewer questions were asked during encounters with non-Hispanic Black patients (3.9) and Hispanic patients (5.5) vs non-Hispanic White patients (7.8).

- Non-Hispanic Black patients gave the fewest assertive responses to questions (5.6), followed by non-Hispanic White patients (6.0) and Hispanic patients (7.0).

“In this diverse sample of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists used fewer reflective statements, were less attentive to concerns, and expressed less warmth with Black non-Hispanic patients,” the authors concluded.

“Interventions are needed to overcome these striking racial/ethnic disparities in serious illness communication for patients with cancer.”

References

1. Smith CB. Racial and ethnic disparities in end-of-life care. Presented at: 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 2022; Chicago, IL https://meetings.asco.org/2022-asco-annual-meeting/14209?presentation=206074#206074

2. Frydman JL, Gelfman LP, Morillo J, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in serious illness communication for patients with cancer. Presented at: 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 20022; Chicago, IL. Abstract 6540. https://meetings.asco.org/abstracts-presentations/206735

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More

Building Trust: Public Priorities for Health Care AI Labeling

January 27th 2026A Michigan-based deliberative study found strong public support for patient-informed artificial intelligence (AI) labeling in health care, emphasizing transparency, privacy, equity, and safety to build trust.

Read More

Ambient AI Tool Adoption in US Hospitals and Associated Factors

January 27th 2026Nearly two-thirds of hospitals using Epic have adopted ambient artificial intelligence (AI), with higher uptake among larger, not-for-profit hospitals and those with higher workload and stronger financial performance.

Read More

Motivating and Enabling Factors Supporting Targeted Improvements to Hospital-SNF Transitions

January 26th 2026Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) with a high volume of referred patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias may work harder to manage care transitions with less availability of resources that enable high-quality handoffs.

Read More