- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

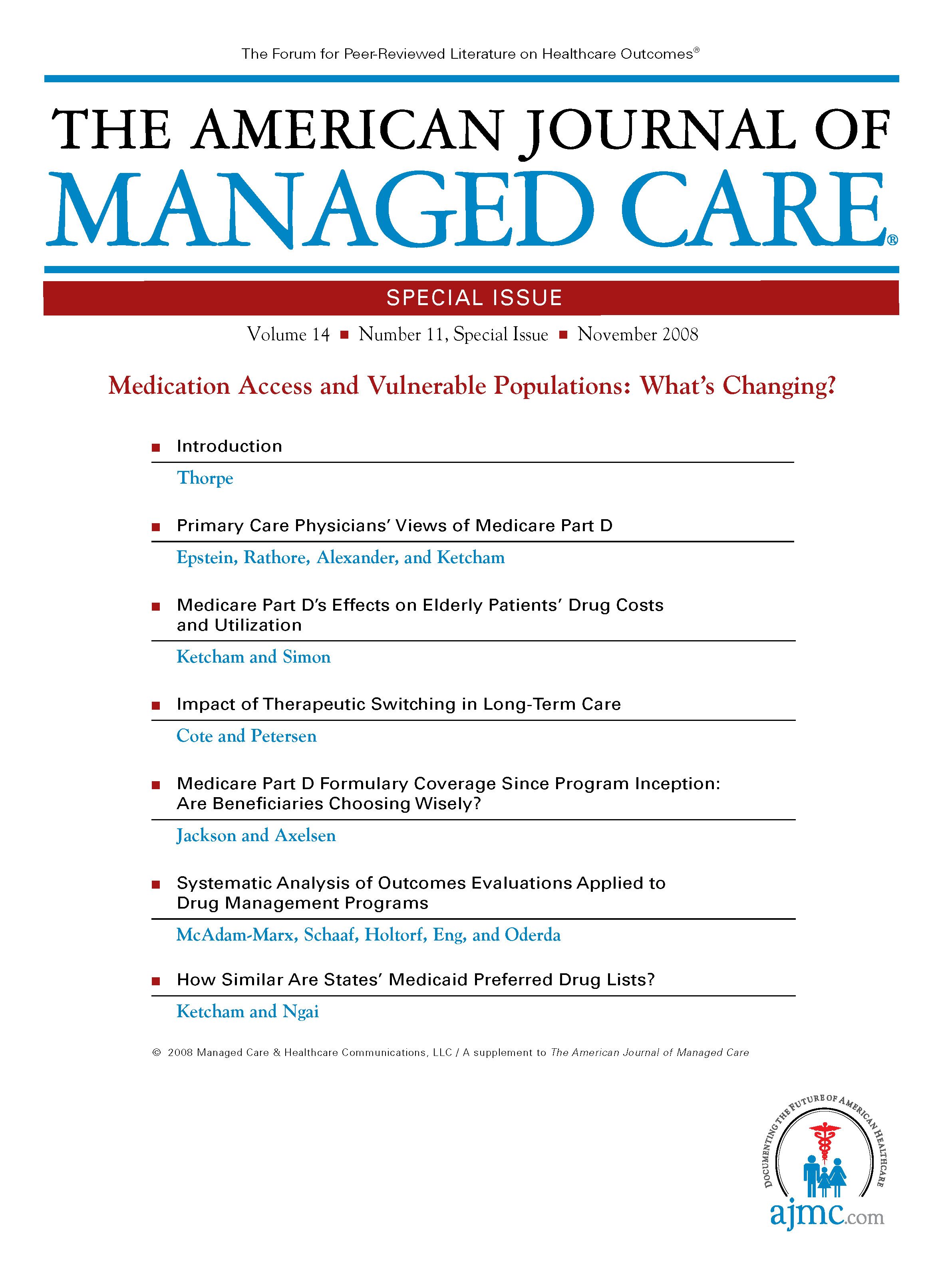

How Similar Are States' Medicaid Preferred Drug Lists?

Comparison of the generosity and consistency of 10 states' Medicaid preferred drug lists for the top therapeutic classes revealed a large degree of inconsistency.

Objective: To compare the generosity and consistency of 10 states’ Medicaid preferred drug lists (PDLs) in high-volume therapeutic classes.

Study Design: Descriptive comparisons of 7 of the top 10 therapeutic classes by Medicaid sales and of the top 10 most populous states with Medicaid PDLs.

Methods: A PDL specifies which drugs are available to patients without receiving prior approval from the state. State PDLs were collected in January 2008 to determine the status (covered or not covered) of 110 different drugs in each state. The US Food and Drug Administration Orange Book provided patent status for each drug. States were compared for generosity and similarity of coverage overall, by patent status, and by therapeutic class.

Results: For 42 (38%) of the drugs, there was wide consistency in PDL design, with at least 9 states classifying the drug with the same PDL status. For the other 62% of drugs, there was greater variation, with 2 or more states classifying the drugs differently than the others. Generosity and consistency also varied by therapeutic class and patent status.

Conclusion: For most drugs, Medicaid PDLs are not implemented consistently across states, suggesting that states do not rely on common clinical evidence to make value-based coverage decisions. Greater involvement by the federal government in designing or regulating monopolistic Medicare Part D PDLs may result in similar inconsistencies.

(Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(11 Spec No.):SP46-SP52)

Medicaid programs use preferred drug lists (PDLs) to control prescription drug spending. Comparison of the generosity and consistency of PDL coverage in the 10 most populous states, with PDLs for 110 active ingredients in 7 of the top therapeutic classes, showed that:

- For 62% of ingredients, at least 2 states differed from the others in their coverage decisions.

- States did not consistently apply clinical evidence to make value-based coverage decisions.

State and federal governments have changed the prescription drug benefits available to Medicaid and Medicare enrollees throughout the past decade. In response to high growth rates in prescription drug spending, state Medicaid programs have implemented numerous policies to control costs. One common strategy is to use preferred drug lists (PDLs). Preferred drug lists establish which drugs are available to patients immediately and which require patients’ physicians or pharmacists to request prior authorization (PA) from the government. Prior authorization often is used in conjunction with “stepwise” or “fail-first” regulations that require a patient to unsuccessfully try a drug covered by the PDL before PA is granted.

Preferred drug lists fall in the middle of the range of formulary design, with open formularies at one end and closed formularies at the other. Open formularies provide insurance coverage for any drug, whereas closed formularies provide coverage only for drugs on the formularies. The credible threat to exclude certain drugs from coverage is shared by both closed formularies and PDLs, and enhances payers’ ability to bargain for lower prices. In addition to lowering negotiated prices, closed formularies and PDLs can reduce spending by shifting prescribing decisions toward lower-cost alternatives.

Previous research indicates that PDLs have lowered states’ growth in prescription drug spending.1 Other work using microdata found that PDLs have altered prescribing decisions,2 and in some contexts this appears to have negative implications for quality.3 PDLs also appear to restrict patients’ access to medications, particularly for newer drugs that have been linked to higher quality,4,5 and to reduce patient adherence to continuing medication therapy.6 These effects of PDLs occur despite their coupling with PAs, likely because the unreimbursed administrative burden of requesting PA promotes greater prescribing of drugs covered by the PDL.7,8

Despite these concerns with Medicaid PDLs, state PDL design might reflect value-based purchasing principles if the cost savings exceed the costs associated with the negative effects of PDLs. If states’ pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees rely on scientific evidence to weigh these tradeoffs, they can create PDLs that promote value-based prescribing, for example, by covering generic products but excluding much costlier on-patent therapeutic substitutes with potentially higher marginal effectiveness. If states’ P&T committees rely on a consistent base of national or international clinical evidence, then the resulting PDLs themselves should be largely consistent across states. Recent efforts have focused on promoting Medicaid programs’ use of clinical evidence; for example, the Foundation of Managed Care Pharmacy established a standardized format for drug manufacturers to report data regarding drugs’ value for use by P&T committees.9,10 Additionally, a number of state Medicaid agencies have joined the Drug Effectiveness Review Project, which combines existing research about the comparative value and outcomes of drugs in a given therapeutic class into a single source available to both member and nonmember states.11

We examined the level of generosity and extent of agreement among states’ prescription drug coverage decisions, as well as how coverage and consistency varied with patent status and therapeutic class. The purpose was to gain insight into whether states’ formulary designs rely on a consistent evidence base, or whether states differ in their criteria for determining coverage. Existing research indicates that states had diverse coverage prior to the recent growth in adoption of PDLs and the growth in evidence-based medicine and economic evaluations of drugs.12 Research on private insurers likewise indicates substantial variation in formulary design because of various organizational characteristics.13 Other researchers found that neither Florida’s Medicaid formulary nor a private formulary had evidence-based or value-based designs.14

METHODSBecause state Medicaid PDLs are not available in an electronic, easily comparable format, we limited the scope of the analysis to the largest states and therapeutic classes. Specifically, we gathered state Medicaid PDLs in place as of January 2008 to examine 1100 formulary design decisions (110 drugs in 10 states). We determined which states had PDLs from a survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation15 and, for nonrespondents, by examining each state’s Medicaid Web site. Of the 37 states that have implemented PDLs, we included in this study the 10 most populated: Illinois, Florida, Texas, New York, California, Ohio, Michigan, Georgia, Virginia, and Massachusetts.

To choose which therapeutic classes to study, we ranked them using the Universal System of Classification (USC) based on their Medicaid sales in the 12 months before March 2008 as reported by the Wolters Kluwer Health’s Pharmaceutical Audit Suite tool.16 We included 7 of the top 10 3-digit USCs: analgesics-narcotics (USC 022), anticonvulsants (USC 202), antidepressants (USC 643), antihyperlipidemics (USC 321), antipsychotics (USC 641), antiulcerants (USC 234), and inhaled steroids (USC 284), and excluded antibiotics (USC 151), HIV antivirals (USC 821), and analeptics (USC 645). Because of legal requirements preventing states from limiting access to critical care, states have exempted certain therapeutic classes from their PDLs, essentially leaving the formularies open for those classes. Thus, we excluded HIV antivirals, which were exempted from all of the state PDLs in this study. We excluded antibiotics because states often covered some of a drug’s strengths and formulations but not others. We excluded the tenth highest-selling class, analeptics, because as central nervous system stimulants they were subject to additional restrictions beyond the PDL in Michigan and New York, and PDL coverage of a given drug varied by patient age in Georgia and California. We examined PDL status at the active-ingredient level, which we refer to as a “drug.” Because we considered only the drug level, we excluded differences across states by formulation, strength, brand name, or other specific aspects of a product. Together, the 7 therapeutic categories included 110 different drugs that accounted for 39% of Medicaid sales (by dollars) nationwide for the 12 months before March 2008.16 Each of these therapeutic classes had been reviewed previously by the Drug Effectiveness Review Project. Patent status for each drug was obtained from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Orange Book. Drugs were characterized as off patent when the FDA Orange Book listed therapeutic-equivalent drugs that were sold by drug manufacturers other than the proprietary manufacturer, or when any form or strength of the drug became off patent. Table 1 lists the therapeutic classes chosen and the number of drugs, the proportion of drugs on patent, and which states exempted the category from their PDLs.

We examined each state’s PDL to determine whether each drug was covered. Drugs were deemed covered if they were listed with preferred status or did not require PA, or if the class was exempted from the PDL altogether. (The Massachusetts PDL occasionally designates for some specific drugs that PA is required if more than 30 units are required per month. In these cases, if PA was required only for supplies for more than 1 month, the drug was still counted as being on the PDL.)

Because states sometimes distinguish between a drug’s brand and generic versions or between different formulations (eg, extended release vs short acting) in their coverage decisions, we considered a drug to be covered if any version was available without PA. Combination products of 2 or more drugs were viewed as distinct drugs, and they were considered on patent if any of the drugs were on patent.

Using these data, we generated descriptive results and where appropriate performed Fisher’s exact tests or t tests to indicate the generosity of coverage and the degree of consistency in coverage across states. Specifically, generosity was measured by the proportion of drugs that were covered by each state. Consistency was measured by the number of states that had the same coverage for each drug. For example, states were considered unanimous on a given drug’s status either if none included it on the PDL or if all 10 did, but they had the greatest disagreement if 5 states included the drug and the other 5 did not.

RESULTS

States’ Medicaid PDLs differ substantially in their coverage of drugs in the highest-selling therapeutic categories. This variation across states could result from several sources, each with different implications. The variation might indicate that PDL coverage decisions do not reflect value-based purchasing despite recent efforts to facilitate it. This situation could result if a sufficient evidence base does not exist, or if state Medicaid agencies do not systematically incorporate existing evidence into coverage decisions. These shortcomings could be addressed through the development of more clinical evidence and more readily available evidence in an easily usable format through programs such as those currently conducted by the Foundation of Managed Care Pharmacy and the Drug Effectiveness Review Project.

The differences in PDLs could be consistent with value-based coverage if states differ with respect to the relative costs or benefits of specific drugs. Specific drugs’ relative benefits might vary, for example, because of differences in the characteristics of states’ Medicaid enrollees. Relative costs might vary because of supplemental discount programs, although the fact that some states receive systematically larger discounts cannot itself explain the observed inconsistencies in PDL coverage. Rather, if discount programs cause some states to receive larger discounts for one drug than others in the therapeutic class, while other states receive larger discounts for different drugs, these differences in relative prices could result in differences across states in the relative values of drugs in a class. That likely would result in less similarity for on-patent drugs than for off-patent drugs, the opposite of what we found. Nevertheless, additional research should consider whether states that achieve identical discounts through state purchasing pools such as the National Medicaid Pooling Initiative have more homogeneous PDLs as a result.17 PDL coverage decisions themselves can influence a state’s discount for a particular drug because they can be made before such discounts are negotiated in every state but Texas.18

We also found substantial differences across classes in consistency and generosity of PDL coverage. Because of concerns about quality and the clinical heterogeneity of patients’ responses to specific drugs, several but not all of the study states exempted anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and antidepressants from PDL restrictions, resulting in their being the most widely covered classes. Despite 3 states agreeing to cover all antipsychotics and antidepressants, other states’ use of PDLs for these classes resulted in greater disagreement than that observed in the other therapeutic classes examined. States’ exemptions of these classes suggest that these drugs are not close substitutes and the differences in PDLs that we observed are, in fact, clinically important. Heterogeneity in clinical response to drugs across patients has been observed for other therapeutic classes studied here as well.19,20 Finally, we found that states somewhat frequently did not cover any on-patent drugs in a therapeutic class, limiting patients’ access to potentially beneficial medications. We analyzed only the therapeutic classes with the greatest sales, leaving open questions regarding coverage of other classes.

States might be similar or dissimilar along dimensions not considered here, including differences by brand, strength, and formulation of a given drug; the levels and tiers of copayments; the stringency of PA requirements and other supply-side controls such as stepwise (“fail-first”) requirements or monthly prescription count limits; and whether Medicaid managed care plans’ formularies also varied. Because we considered only coverage decisions, our findings likely under-represent the total degree of variation across states’ formularies. Research also should illuminate what drives this variation across states’ coverage decisions. Research focusing on the processes by which Medicaid P&T committees make their PDL coverage decisions will result in greater understanding of whether these differences result from differences in use of available evidence, the values of the committee (eg, the willingness to trade off access for cost reductions), drug discounts, the makeup of the P&T committee, or other differences in the political process. Finally, decision makers themselves could benefit from more evidence about the implications of specific formulary coverage decisions for costs and quality.

State pharmacy benefits managers should consider the extent to which the outcomes of their coverage decisions differ from those of their peers in other states. These managers have access to information not available to health services researchers such as ourselves to discern whether the inconsistencies reflect a lack of value-based coverage. For example, they can observe their states’ negotiated discounts. In addition, the state P&T committees include clinical experts to evaluate the quality effects of less generous and less consistent coverage, particularly whether consistency and generosity are more important for some therapeutic classes. States seeking to implement more value-based coverage decisions could benefit by learning from their counterparts in other states, as well as increasing their reliance on standardized information available from organizations such as the Drug Effectiveness Review Project.

The variation in prescription drug coverage that exists in private markets and in the managed competition approach of Medicare Part D benefits consumers by allowing them to choose a plan according to personal, heterogeneous values for specific drugs, although this comes at the cost of greater complexity for physicians.21 However, when patients cannot choose their plans, such as in Medicaid and under proposals for regional or national monopolies for Medicare Part D,22 variation in formulary design is not desirable if it reflects a lack of value-based coverage decisions. The variation across states’ Medicaid PDLs observed here raises concerns that such regional or national formularies in Part D would not reflect value to patients even on average, particularly given the higher stakes for various political interest groups in Medicare formulary design.

CONCLUSION

Acknowledgments

2. Virabhak S, Shinogle J. Physicians’ prescribing responses to a restricted formulary: the impact of Medicaid preferred drug lists in Illinois and Louisiana. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(1 Spec No.):SP14-SP20.

4. Lichtenberg F. The effect of access restriction on the vintage of drugs used by Medicaid enrollees. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(1 Spec No.):SP7-SP13.

6. Wilson J, Axelsen K, Tang S. Medicaid prescription drug access restrictions: exploring the effect on patient persistence with hypertension medications. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(1 Spec No.):SP28-SP34.

8. Ketcham JD, Epstein AJ. Medicaid preferred drug lists’ costs to physicians. Med Care. 2008;46(1):9-16.

10. Berk M, Schur C, Gupta J. Insights into Formulary Decision Processes: Findings from a National Survey of Health Plans. Silver Spring, MD: Social & Scientific Systems, Inc; March 2008. http://www.fmcpnet.org/cfr/waSys/f.cfc?method=getListFile&id=3EE4422A. Accessed September 8, 2008.

12. Moore WJ, Newman RJ. Drug formulary restrictions as a costcontainment policy in Medicaid programs. J Law Econ. 1993;36:71-97.

14. Neumann PJ, Lin PJ, Greenberg D, et al. Do drug formulary policies reflect evidence of value? Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(1):30-36.

16. Wolters Kluwer Health. Source® Pharmaceutical Audit Suite Tool. http://www.wkhealth.com/pt/re/ps/source.htm. Accessed October 20, 2008.

18. Health and Human Services Commission. Analysis of Multi-state Medicaid Drug Purchasing Pool. http://www.hhsc.state.tx.us/reports/Multi-State_MedicaidDrugPurchasing.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2008.

20. Mangravite LM, Thorn CF, Krauss RM. Clinical implications of pharmacogenomics of statin treatment. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6(6):360-374.

22. Huskamp HA, Rosenthal MB, Frank RG, Newhouse JP. The Medicare prescription drug benefit: how will the game be played? Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(2):8-23.

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More

Building Trust: Public Priorities for Health Care AI Labeling

January 27th 2026A Michigan-based deliberative study found strong public support for patient-informed artificial intelligence (AI) labeling in health care, emphasizing transparency, privacy, equity, and safety to build trust.

Read More

Ambient AI Tool Adoption in US Hospitals and Associated Factors

January 27th 2026Nearly two-thirds of hospitals using Epic have adopted ambient artificial intelligence (AI), with higher uptake among larger, not-for-profit hospitals and those with higher workload and stronger financial performance.

Read More

Motivating and Enabling Factors Supporting Targeted Improvements to Hospital-SNF Transitions

January 26th 2026Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) with a high volume of referred patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias may work harder to manage care transitions with less availability of resources that enable high-quality handoffs.

Read More