- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

ASCO 2023: Payment Models and Policy

Coverage of ASCO sessions and posters that addressed lessons from the Oncology Care Model and concerns about the Enhancing Oncology Model, which launched shortly after the annual meeting ended.

ASCO Panel: Do Medicare Oncology Payment Models Measure Value, or Just Savings?

Editor’s Note: The Enhancing Oncology Model started on July 1, 2023, as this special issue of Evidence-Based Oncology went to press.

With Medicare’s latest payment model in oncology set to launch within weeks, experts gathered on June 4 during the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) to explore where the last major reimbursement scheme succeeded and where it didn’t—and whether the final report card was truly fair.

The session, “Payment Reform: Lessons Learned from the Oncology Care Model (OCM) and Implications for the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM),” moderated by oncologist Gabrielle Betty Rocque, MD, MSPH, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, featured leaders from 2 large oncology practice networks and 1 representing academic medicine:

- Aaron Lyss, MBA, director of strategic payor relations, OneOncology, who spoke on strategies to achieve success in the OCM;

- Theresa Dreyer, MPH, manager, value-based care, Association of American Medical Colleges, who discussed perspectives from academic practices in the OCM; and

- Lalan Wilfong, MD, senior vice president, payer and care transformation, The US Oncology Network, who shared his perspective on the Enhancing Oncology Model.

Lyss

From the start, Lyss didn’t sugarcoat it: “Practice transformation is really hard.”

To make models viable from an economic perspective, he said, they can’t succeed only within the confines of Medicare—practices must be able to create economies of scale that work with commercial plans as well. Lyss outlined the fundamentals: Practices must improve access to clinical trials, use clinical pathways, and minimize use of the emergency department (ED). They must deploy distress screening, palliative care, and chronic care management. And underlying it all must be the use of data analytics to continually measure success and track and fix problems.

As an example, he cited Tennessee Oncology’s Oncology Medical Home partnership with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee. “Tennessee Oncology is able to use the same pain and distress screening quality reporting that they utilize for the Oncology Care Model, and apply that to their commercial population,” Lyss said.

But if commercial and Medicare Advantage plans want true value-based partnerships in oncology, he warned, it must be a 2-way street. For these ventures to be viable from the practices’ side, oncologists must be freed from the burden of prior authorization and utilization management, and they need to make their own clinical and business decisions about the tools of delivering care—starting with preferred agents and extending to which labs, genomic tests, and other ancillary services to use.

In particular, he said, “This iron wall between the medical and pharmacy benefit is a construct that was not designed for cancer care, and it doesn’t make any sense when it comes to managing patients with cancer.

“We have to figure out ways to integrate value-based care across both the medical and pharmacy benefit, where we have those opportunities,” Lyss stressed.

The EOM will take effect on July 1, a year after the expiration of the OCM, its predecessor. There are many similarities and some key differences between them, which Lyss identified:

- The EOM will have no alternative payment model incentives for more aggressive risk management.

- Risk management requires 2% cost savings from the start of the EOM to avoid financial penalties.

- Episode pricing methods in the EOM lack sensitivity to clinical and quality parameters of value.

All of this, Lyss said, adds up to a lot of risk for any practice, without much of a sense that practices are being measured for offering good care. And the question is: Why?

The answer is the OCM evaluation report, which examined how well practices in the earlier model did in achieving savings—and found that they fell short. But Lyss explained that the government contractor evaluating the OCM lacked access to key information that might have allowed insights into how well OCM practices actually did in improving care quality, compared with national benchmarks.

Lyss highlighted other conclusions the report reached—including that OCM practices generated savings by using lower-cost supportive care medications. The fact that this report is the “official record” of the OCM, one that drove a new model that creates high levels of risk for practices, “tees up the other panelists to talk about the importance of using clinical data and the importance of more robust research in oncology payment reform.”

In Academia, Innovation and Drug Costs Drive Losses in Model. Dreyer shared data on 30,000 cancer episodes from 2016 to 2020, just before the pandemic, which showed how incorporating clinical data into the equation can make the difference between success or failure. On her chart, the trends for breast and prostate cancer showed 20 academic practices staying on target within 1-sided risk models, while the losses piled up for lung and multiple myeloma, for a net negative of $14 million.1

“So, what is different here, between prostate and breast [cancer]?” she asked. “One way to CMS might interpret this would be [to say this shows] the incentives of selecting a certain drug for profit margin. Another way to interpret this [would be to say] that risk adjustment is really hard. And if you eliminate all clinical data from the risk adjustment for our patient with cancer, it doesn’t suffer. It’s not sufficiently nuanced to talk about differences in risk within a given condition and within a given cancer,” she said.

But Dreyer pointed to the spot on the chart at Payment Period 3, when CMS introduced a change in the risk of assessment, “where they use treatment regimen as a proxy for clinical indicators—and they created this high- and low-risk distinction in breast and prostate cancer.”

At that point, one can look at the chart and see how this policy change caused the data to move into positive territory for the 2 cancers affected by the change. By contrast, the losses keep mounting for lung cancer and especially for multiple myeloma, which were going through a period of intense innovation. Dreyer noted that in lung cancer, the cost of therapy went from 40% of a total episode to 70%, and for multiple myeloma it went from 2% to 70%. “That differential wasn’t fully accounted for in the risk adjustment,” she said.

“So do the missing clinical data explain the results? That was a question that we had,” Dreyer said, bolstering Lyss’ point about the fact that practices submitted clinical data to CMS for every cancer type. Based on what is being proposed in the EOM, it seems this phenomenon could strike twice. As many know, the number of cancers EOM will cover is limited to 7, and Dreyer said that adjustments will take place for metastatic lung, colorectal, and HER2+ breast cancer. “There will be no clinical risk adjustment of any kind for multiple myeloma,” she said.

It’s not all bad news. Reporting will still be required, and models will be built by cancer type, so adjustments would occur within the models themselves. Dreyer said some analyses her group has done show that calculations are more precise than in the old OCM. “But I think that for participants, the limited use of the clinical data that are being reported by the practices is something to watch and be cautious about,” she said. “The fact that the data are being recorded doesn’t mean that CMS has the data available that they need to do analyses similar to the ones that we did,” at AAMC.

Alternatives for payers include alignment with pathways and use of registries to obtain data, she said.

EOM: The Levers to Push and Pull. The next payment model is coming, Wilfong said, and the question becomes: How to succeed?

He showed pie chart that displayed “where the money goes,” in cancer care; it allotted 72% of costs to drugs, with smaller shares to hospital costs, care management, and ancillary costs such as imaging and labs. Wilfong said oncologists must grapple with the issue that CMS’ policy raises: The current reimbursement structure, known as “buy and bill,” gives doctors a percentage of each drug’s cost. In effect, they have incentives to order expensive drugs.

Wilfong

Wilfong pointed to 3 strategies to mitigate drug costs: (1) use of pathways, in which oncologists agree to follow guidelines-driven treatment regimens agreed upon by consensus of their academic center, health plan, or practice network; (2) therapeutic interchanges, in which reimbursement models create incentives to promote lower-cost drugs, such as biosimilars; and (3) appropriate use criteria, which look at trends, such as rising use of growth factors, and ask if there are ways to reduce their use, such as dose reduction, without any change to efficacy.

Both the OCM and many commercial value-based agreements have incentives for reducing drug costs. “If you can utilize drugs more effectively, then you have a much better chance of coming up under your benchmark and being financially rewarded for saving money in these models,” Wilfong said.

“We had a very rapid adoption of biosimilars in our network,” he continued. Near the end of the OCM, “We were up to 89% of biosimilars and our network far exceeded the national averages [in that regard], which are still lagging at around 50% to 60%. If you look at some of the recent studies in Health Affairs about smart adoption, biosimilars are a lot less expensive than the brand drugs. So, you’re able to bend the cost curve, when we show that it was more than 1% of total cost to care reduction just by using biosimilars.”

Practices can find savings in other areas, such as drugs for supportive care, including those for bone health, by taking time to use lower-cost options.

Reducing hospital costs by keeping patients out of the ED was an early cost-reduction strategy under the OCM, and most practices adopted practice transformation strategies such better phone trees and same-day appointments to address this. More recent steps include the use of electronic patient-reported outcomes and geriatric assessments to modify treatments for those at risk of poor outcomes.

Wilfong listed the questions that must be asked to challenge the status quo:

- Are we screening our patients appropriately?

- Are we addressing health-related social needs? He said studies show that up to 80% of the total cost of care—not just in oncology, but in medicine generally—are due to these factors.

- Are we thinking about end-of-life care?

To that end, Wilfong pointed to a recent study that said it cost $60 per patient to screen for social needs2—or $10 less than the new, reduced payment for Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services under the EOM.

Tracking social needs is important, he said. “Hopefully, none of us [would argue] that it’s not important to do that. But it’s pretty expensive.

Navigation services are expensive. You have to hire staff, you have to hire nurses, you have to fix your call center in order to do that. So, is this where you focus if you’re going into a model like this?”

The challenge is that there are other required services under EOM that are also important—such as advance care planning—and possibly not enough resources to cover them all. There are questions about basic care delivery: More therapies require molecular testing, for instance, and practices must ensure that these tests are being used appropriately, because those costs accumulate. The same is true of imaging.

“These are the things driving the cost of care, so those are the things you have to think about as an. administrator, as you think about going into a value-based care model,” Wilfong said.

For practices considering the EOM, the first question is, “Where do you start?”

References

1. Dreyer TRF, Hamilton E, Dahl A, et al. Evaluating the addition of clinical and staging data to improve pricing methodology of the Oncology Care Model. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(11):e1899-e1907. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00211.

2. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Davis C, Drake C, Phillips RL, Landon BE. Estimated costs of intervening in health-related social needs detected in primary care. JAMA Intern Med. Published online May 30, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1964

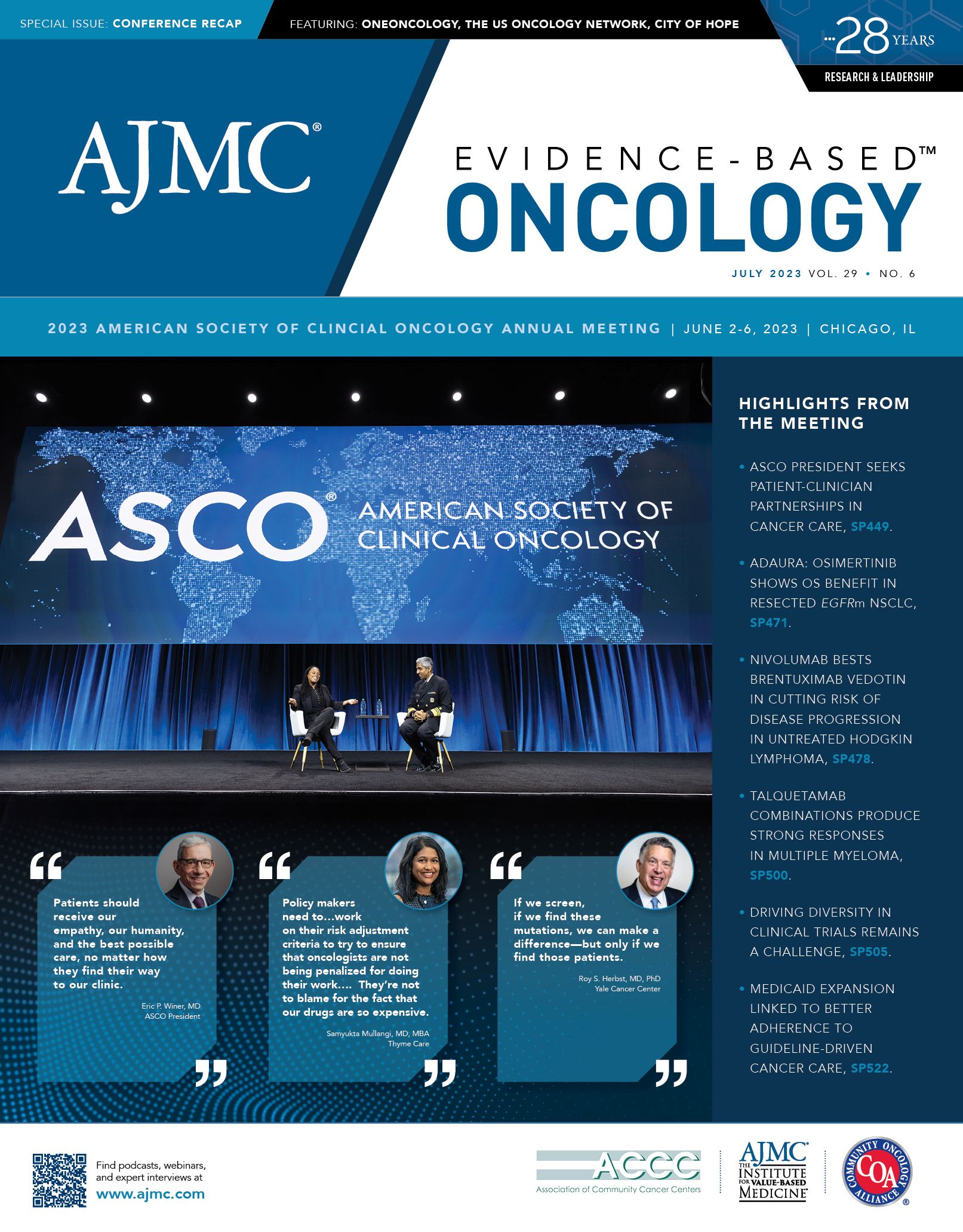

SPOTLIGHT: Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, on the EOM: MIPS Disproportionately Penalizes Oncologists; ePROs Need Refining

Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, incoming medical director at Thyme Care, has recently published research suggesting that oncologists will likely be disproportionately penalized after the incorporation of cost measures into

Mullangi

the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) under the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM).1 In an interview with Evidence-Based Oncology (EBO) ahead of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, Mullangi explained the implications of MIPS composite scores for oncologists and described some barriers with electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePROs).

This year at ASCO, Mullangi presented data on the association between Oncology Care Model participation and spending, utilization, and quality outcomes among patients with commercial insurance and Medicare.2

EBO: How can specialty-specific solutions maintain health care quality and outcomes amid value-based care policy efforts?

Mullangi: All physicians who are participating in Medicare are subject to quality performance review activities, either through MIPS or Advanced Alternative Payment Models [APMs]. In MIPS, clinicians earn a yearly composite score that is based on 4 domains: cost, quality, improvement activities, and achieving interoperability. Whereas clinicians who are participating in Advanced APMs are exempt from MIPS reporting requirements, clinicians who are participating in non-Advanced APMs may still participate in MIPS. This is important because, for example, within oncology, physicians who are going to participate in the upcoming Enhancing Oncology Model—definitely for 2023 and, for many practices, even into 2024—will not meet either the payment or the patient volume criteria to qualify them to be an Advanced APM, so they may still end up participating in MIPS.

MIPS is not a perfect program. It’s a really nice amalgamation of all of the reporting requirements that came before it, but it still has some problems. One that I see is that the cost criteria within MIPS is just a global measure that’s specialty agnostic—it’s just basically looking at spending per beneficiary. In some previous work that we published this year in The Oncologist,1 we found that oncologists who treated patients of greater clinical complexity were also receiving lower composite MIPS scores, and much of that was actually driven by their performance on the cost metric. Our work actually used data from 2019, back when the cost metric only accounted for 15% of the MIPS composite score and quality accounted for 45%. As of 2022, those things have equalized—they’re 30% each—and we hypothesized that oncologists who treat these high-complexity, high-cost patients would be treated disproportionately unfairly in the program.

In some follow-up work, we actually studied this very question. We obtained publicly reported MIPS category scores for physicians from the year 2018, and then we applied the 2022 new reweighting criteria to their performance back then. We found that oncologists of every subspecialty—medical, surgical, radiation—were all being given disproportionately low composite scores relative to their non-oncology peers. And they actually, with the reweighting, sustained the biggest decrease in absolute numbers in this composite score, and that translates to big implications. So, 40% of oncologists will now not receive an exceptional payment bonus, and the maximum penalty has increased from $4000 to $18,000 per physician. This has really, really big implications.

We did some sensitivity analyses to understand whether this was being driven by just clinical complexity. We found that it did explain some of it, [but] it also didn’t fully explain it. So, yes, clinical complexity is associated with a lower composite MIPS score. But we found that oncologists who were treating patients of every decile of clinical complexity had lower composite MIPS scores than non-oncologists. And within the oncology subspecialties, medical oncology had the lowest mean cost score relative to surgeons and radiation oncologists.

I think there’s a problem. I think policymakers need to look at this and try to work on their risk adjustment criteria to try to ensure that oncologists are not being penalized for doing their work. I mean, they’re not to blame for the fact that our drugs are so expensive and that the cost of [providing] our care is so high. It’s really important going forward; MIPS is the backbone of so many practices’ value-based payment programs. It’s really important that oncologists are on level footing with the rest of their medical peers.

EBO: What are barriers do practices face in using ePROs and in developing their own tools for reporting social determinants of health? What solutions would you like to see?

Mullangi: I think the emphasis on increased reporting on social determinants of health and electronic patient-reported outcomes is great in theory, because there are a lot of data—randomized clinical control data—showing that obtaining this information about our patients and then acting on it leads to a better care experience and better clinical outcomes. But there are a couple of things that I think are a little bit tough with the emphasis on doing so with a model like the EOM.

One is that these are process measures. There’s really no accountability on practices to necessarily match resources to the data. So, if a patient reports a problem like food insecurity, yes, practices will probably respond to that, but right now CMS is only looking at the process measure of having collected those data. And the other thing is that the EOM gives practices less upfront money through these monthly enhanced oncology services—[lower] payments, these per-member per-month payments— that practices previously used to furnish these types of transformation activities. So standing up a big reporting program like this, where you’re systematically collecting these data from patients and then matching them to resources that could help them address whatever needs that they’re bringing up, that’s a big enterprise and I think practices need funding to do so. So, it would be really nice if that was available.

But the other thing I’ll say to your question is this: I don’t think that practices should be in the business of trying to develop these tech tools on their own. This is not an activity that requires some kind of custom bespoke tool. There are so many off-the-shelf tools that have been “battery tested,” that have been optimized for the user experience, that are based on best practices, that I think, honestly, that practices should just procure one of those and spend most of their energy trying to understand how you develop these workflows to do this big activity. And then—notwithstanding whatever funds are coming from CMS—how do you actually stand up programs that would meet the patient’s needs?

References

1. Patel VR, Cwalina TB, Gupta A, et al. Oncologist participation and performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. Oncologist, 2023;28(4):e228-e232. doi:10.1093/oncolo/oyad033

2. Mullangi S, Ukert B, Sylwestrzak, G, et al. Association of participation in Medicare’s Oncology Care Model with spending, utilization, and quality outcomes among commercially insured and Medicare Advantage members: a national difference-in-differences analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16);abstr 1596. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1596

Poster Talks Explore How Policy, Payer Incentives Affect Cancer Care, Outcomes

For all the therapeutic advances presented during the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, there are simple realities: Patients cannot be treated if they have no access to care. Too many patients miss a chance at survival for such reasons: They lack health coverage, they can’t take a day off, or they can’t navigate the system.

At the same time, therapy given when patients won’t benefit helps no one; this drives up the costs and wastes resources better spent improving the quality of end-of-life care.

No one knows this more than oncologists themselves, and on June 5, 2023, a group gathered for a session of talks on care delivery and regulatory

Blau

Williams

policy. This session, chaired by Sibel Blau, MD, medical director of Northwest Medical Specialties and president and CEO of the Quality Cancer Care Alliance, and Vonetta Michele Williams, MD, PhD, radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, invited speakers to frame presentations around 3 related posters selected from the thousands accepted for the ASCO meeting. The first 2 talks addressed payer resource issues, including the now-expired Medicare payment model, the Oncology Care Model (OCM).

Medicaid Expansion and Paid Leave Both Linked to Improved Survival. Matthew F. Hudson, PhD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville, discussed 3 posters involving access to care:

An analysis led by Xuesong Han, PhD, director of Surveillance and Health Services Research at the American Cancer Society, compared data for young women with breast cancer in Medicaid expansion states and those that did not expand Medicaid; they found that Medicaid expansion was linked to increases in guideline-concordant care, fewer treatment delays, and improved 2-year survival. More shocking was the finding that guideline-concordant care and 2-year survival rates for young patients with breast cancer fell over time if states failed to expand Medicaid.1

Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn Medicine), and colleagues found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant increase in the share of Black and Hispanic patients taking part in oncology clinical trials if states required Medicaid to cover trial costs.2

A study led by Justin Michael Barnes, MD, MS, radiation oncologist, Washington University in St. Louis, found state paid medical leave requirements were linked to improved survival for working-age adults with newly diagnosed cancer, especially if they lacked insurance.3

Why don’t such findings lead to better access for all? As Hudson explained, developing these data is just the first step. “We can glean from this that federal and state policy favorably correlates with evidence generation, cancer care, delivery, research, and health outcomes,” he said. “But at this point, we might need a reminder fundamentally to explore, what, in fact, is policy?”

Policy, he asserted, has many elements: It is a set of principles, it requires people to act, and it calls for assessments of those actions. The challenge with implementing policy, Hudson said, is that it requires a level of consensus that may not exist.

“If we contemplate policy as a principle or tool, we’d argue that state policy provides knowledge,” he said. “That is, it publicly declares an ethical stance of right and wrong. It also encourages or challenges moral perceptions, the subjective beliefs related to this ethical stance.”

Hudson continued: “It assumes skills. That is, it assumes a compliance capacity, and it expects compliance behavior. Now, it expects this of individuals of groups and organizations, all in service of advancing patient outcomes. So policy as an intervention expects [that] its mere presence begets organization, group, and individual change that produces patient-centered outcomes.”

The results Hudson highlighted—which showed both the benefits of access to care and the harms of poor access—point to the next phase of research, which would be policy implementation science. Who are the “actors” at the state or federal levels who can advance the public’s health? What steps would be needed to translate these results into action?

While Han and colleagues focus on health care access, Hudson said: “I think there’s an opportunity in future research to think critically about which regional planning policies interact with Medicaid policy to optimize breast cancer outcomes. We may also consider how regional planning policies drive treatment facility availability and its characteristics.”

The opportunity, Hudson said, is “to consider whether treatment affordability impacts survival through adherence or treatment choice.”

He also encouraged the oncologists to start weighing the impact of “time toxicity,” a new concept emerging in cancer care, which considers the time patients spend dealing with the health system bureaucracy and how that affects survival. Simply put, patients who can’t take time off or have no one to help them with prior authorization may give up and forgo treatment.

“How might patients trade home days for survival days?” Hudson asked. “And how might that mediate the impact of paid medical leave policy?”

Evaluating Success in Care Coordination for Patients With Cancer. Kerin Adelson, MD, chief quality and value officer at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, next discussed research on a group of initiatives designed to improve patient care and, where possible, reduce costly and futile end-of-life interventions.

Community health workers. A clinical trial led by Manali Patel, MD, MPH, MS, Engagement of Patients with Advanced Cancer (NCT02966509) randomly assigned 213 veterans with stage III or IV cancer to usual care (UC) or usual care plus a 6-month intervention with a community health worker (CHW), who helped with advance care planning, completion of advance directives, and discussions of goals and values with their clinicians.4

Although prior work has shown how such efforts promote discussions and shrink acute care costs, Adelson said, “Dr Patel asks what the long-term effects of the community health worker intervention were on the overall survival and health care use in the last 30 days of life.”

After a median follow-up of 298 days, results were significant:

- The CHW group had improved overall survival compared with the UC group, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.56-0.98; P = .04).

- The CHW group used less than half the amount of emergency department (ED) and hospital stays in the last 30 days of life as the UC group, with odds ratios (ORs) of 0.33 (0.18-0.63) for ED use and 0.28 (0.15-0.54) for the hospital.

- The CHW group was also more likely to use palliative care than the UC group (OR, 1.86; 1.03-3.33) and hospice (OR, 2.36; 1.28-4.36).

Adelson showed the Kaplan-Meier curves for survival results and remarked, “You could imagine a phase 2 trialist for a therapeutic drug just being ecstatic to show this kind of result.

What is it about a community health worker intervention that worked so much better than many prior studies?” she asked. “Is there more trust when the conversations involve a nonmedical person from the patient’s own community? I would love to know what actually happened in the interactions between the community health worker and the patients,” she said, suggesting a qualitative analysis.

“Finally,” Adelson asked, “Why did the intervention group live longer? Was it related to the higher rates of palliative care use? Was it that help with coping that gave them more reason to live?

Oncology Care Model (OCM). Adelson next took up a timely abstract that examined the OCM, Medicare’s 6-year alternative payment model to improve cancer care. The OCM ended in June 2022 (and is to be replaced with the Enhancing Oncology Model as Evidence-Based Oncology went to press). The analysis, led by Gabriel A. Brooks, MD, MPH, an associate professor of medicine and The Dartmouth Institute at Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, reviewed data through year 5 of the program.5

The authors concluded that the OCM led to a $499 relative reduction in Medicare payments for 6-month episodes, with similar care quality; the biggest savings impact was seen in high-cost cancers; the OCM had no overall impact on chemotherapy spending, but reduced spending on supportive care; and the OCM had no overall impact on ED visits or hospitalizations, relative to practices outside the OCM.

The authors concluded that a significant reason Medicare lost money on the OCM was the size of payments for monthly enhanced oncology services (MEOS), which were required items such as patient navigation, advance care planning, and 24/7 access to records. A major source of controversy among practices considering the EOM is the cut in MEOS payments from $160 per patient per month (PMPM) under the OCM to $70 PMPM.

Also, as practices became more nimble with the OCM, they were also more successful in earning back savings as performance payments, which further eroded Medicare’s savings.

Adelson reviewed which items were and were not included in the OCM quality measures, noting that these included things such as curtailing ED and hospital visits, increasing use of hospice, and screening for pain and depression. Although practices were required to use clinical guidelines, they did not have to demonstrate use or calculate use of systemic therapy at end of life as quality measures. More importantly, Adelson shared an analysis from Tuple Health based on data from Yale Medicine, which showed how drug costs had overtaken other aspects of cancer care: Even if oncology teams found savings elsewhere, it was hard to contain overall costs when drugs climbed from 53% of total cost in 2012 to 71% by 2020.

“In the age of molecular oncology, there are really very few examples of clinical equipoise between high-cost and low-cost, disease-modifying therapies. And I actually think it’s a fantastic sign that the practices demonstrated a willingness to make substitutions when they felt they were clinically appropriate,” she said.

In her conversations with colleagues, Adelson hears of great willingness to substitute biosimilars or other less expensive therapies. “But again, there are very limited opportunities.”

While noting the authors’ findings, Adelson said Medicare lost money because of the program design, not from lack of effort by the practices.

"Whether the program is successful or not, it’s a matter of perspective,” she said. “If you wanted oncology practices to improve quality, at least to some extent, and reduce Medicare billing, then the program was absolutely a success. If you were trying to save Medicare money—if that was your goal, then the program design was flawed from the outset.”

Instead, she said, a payment model more like ASCO’s Oncology Medical Home—which addresses clinical nuances and evaluates practices for values within their control—would do more to promote good care.

Offering a nudge. Takvorian was the lead author for a second abstract, which reported results of a clinical trial (NCT04867850) on the effect of electronic “nudges” to both clinicians and patients to promote conversations about serious illness. Between September 2021 and March 2022, the study tracked 4450 patients seen by 166 clinicians. Evaluations were randomly assigned to the clinician nudge (1179), the patient nudge (997), both (1270), or the active control (1004).

Compared with the control, serious illness conversations were more likely among participants in the combination nudge arm, with an HR of 1.55 (95% CI, 1.00-2.40); and the conversations were not more likely in the clinician arm (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.64-1.41) or the patient arm (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.73-1.33) relative to the control. The authors concluded that a system of 2-way nudges may have a “synergistic” effect in encouraging serious illness conversations in an equitable way across a large health system.6

Adelson reviewed the process that the Penn Medicine team followed for the nudges, including an element of competition among the oncologists in 1 arm by offering comparative feedback.

Although the increase in conversations at 6 months for the combined nudge group was significant, Adelson cautioned, “It was still only 14% of patients who are actually having these conversations, which says we still need to do more as a society. And we need to look at studies like Dr Patel’s that were so successful in moving this needle.”

Misaligned incentives. In looking at which interventions improve survival, Adelson said it’s also important to look at what does not help survival: therapy at end of life.

Adelson shared data her team had presented at ASCO. “One of the criticisms of the metric looking at chemotherapy within 14 days of death is that we’re missing the patients treated at the same time point who go on to live and have the benefit,” she said. “If that’s true, when we compare practices that give lots of chemotherapy at the end of life to those that give less, we should see improved survival for the more aggressive practices.”

Adelson and her team performed this analysis using Flatiron Health’s database, examining the 6 most common cancer types, looking at the entire population and not just those who died.7 “There is absolutely no survival benefit for more aggressive use of chemotherapy in the end-of-life setting,” she said. And this affects downstream care, too, with higher rates in the intensive care unit, higher hospital admissions, and lower hospice rates.

“So maybe we have some misaligned incentives,” Adelson said. “We know that these patient-centered interventions improve survival, reduce acute care use, improve patient and caregiver experience, reduce cost, and, for the most part, are not reimbursed,” except perhaps under evaluation and management billing for palliative care visits.

“Conversely, aggressive use of end-of-life systemic therapy has no survival benefit, increases acute care use at the end of life, harms patient and caregiver experience, increases cost, and could be reimbursed as high as $80,000 a month,” she said, using a common immunotherapy as an example. “The money saved on end-of-life oncolytics and downstream acute care could be redirected to enhanced home hospice services, more flexible criteria for inpatient hospice, and communication training programs.”

References

1. Han X, Shi KS, Ruddy KJ et al. Association of Medicaid expansion with treatment receipt, delays in treatment initiation, and survival among young adult women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr 1511. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1509

2. Takvorian SU, Schpero WL, Blickstein D, et al. Association between state Medicaid policies and accrual of Black and Hispanic patients to cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr 1511. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1510

3. Barnes JM, Chino F, Johnson KJ, et al. State mandatory paid medical leave policies and survival among adults with cancer in the US. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr 1511. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1511

4. Patel MI, Agrawal M, Kapphahn K, et al. Engagement of patients with advanced cancer (EPAC) randomized clinical trial: long-term effects on survival and health care use. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr 1513. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1513

5. Brooks GA, Trombley M, Landrum MB, et al. Impact of the Oncology Care Model (OCM) on Medicare payments, utilization, and care delivery: update through year 5. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr 1512. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1512

6. Takvorian SU, Clifton ABW, Gabriel PE, et al. Patient- and clinician-directed implementation strategies to improve serious illness communication for high-risk patients with cancer: a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr 1514. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1514

7. Adelson K, Canavan M, Sheth K, Scott JA, Westvold S. The impact of receipt of systemic anticancer therapy (SACT) near the end of life (EOL) on cost among oncology practices participating in CMS’ Oncology Care Model (OCM). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):abstr e18923. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e18923

Oncology Practices Made Shifts Toward Biosimilar Use, but Payer Challenges Remain

At the end of 2022, more than half (22 of 40) of the approved biosimilars in the United States were used to treat cancer or for supportive care for patients with cancer. Two abstracts presented at the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting evaluated biosimilar adoption across oncology practices.

The first abstract analyzed the impact of regional clinical pharmacists (RCPs) on selecting the most cost-effective biosimilar products in a large oncology network of 107 oncologists across 76 locations and 17 states.1 The network had implemented a program in October 2021 in which RCPs acted “as a liaison between providers and financial teams to evaluate existing drug orders and their financial impact.”

After 1 year of the program, more than 90% of bevacizumab, trastuzumab, and rituximab orders were for the preferred product. Prior to the program, use of preferred pegfilgrastim was less than 20% in April 2021 and by December 2022 it was above 60%. From April 2021 to April 2022, use of preferred filgrastim had increased from less than 75% to greater than 90%. However, it had decreased to 55% by the end of 2022 as a result of trending average sales price.

The program resulted in significant cost savings. Throughout 2022 there was $56.5 million in total savings—$26.4 million for payers, $23.5 million for providers, and $6.6 million for patients.

The authors noted that in one-third of cases, payer preferences prevented biosimilar switching.

“Barriers to switching to institution-preferred products included non-medical switching requirements by payors, patient assistance and compassionate use programs, and patient and/or provider preferences,” they noted in conclusion.

In the second abstract, the authors conducted a 40-question survey to understand the current state of biosimilars in oncology practices, as well as barriers to uptake.2 The surveys evaluated formulary management, product usage, policies, technology, safety, and education and the biosimilars for bevacizumab, filgrastim, epoetin alfa, infliximab, pegfilgrastim, rituximab, and trastuzumab.

A total of 50 survey responses were included in the analysis, of those 21 (42%) were from National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers.

The responses revealed:

- Formulary decisions were driven first by acquisition cost and then by reimbursement in the inpatient setting and equally by acquisition cost and reimbursement in the outpatient setting.

- 32% only used biosimilars for the FDA approved indications

- 66% had an interchangeability policy

- More than 90% had a preferred biosimilar on formulary

Payers impacted biosimilar use for the respondents: 72% said payers specified biosimilar selection and 76% said payer reimbursement limited the ability to participate in contract pricing. In addition, the main barrier to biosimilar adoption was insurance reimbursement (82%), according to respondents, followed by drug availability (24%) and computerized provider order entry (24%).

Filgrastim had the highest biosimilar use at 88%, followed by epoetin alfa (82%). In comparison, pegfilgrastim had the lowest adoption at 52% followed by infliximab at 57%.

Communication was the main cause for medication error related to biosimilar use and was reported by 26% of respondents.

Despite noted utilization shifts toward biosimilars compared with the reference product, there remain areas for continued improvement, the authors noted.

“Opportunities exist in the collaboration of health systems and payors to align formularies and promote safe and cost-effective care for their members,” they concluded.

References

1. Chang M, Li J, Peters B, et al. Biosimilar uptake and cost savings analysis before and after implementation of a pharmacist-driven substitution program within a national community oncology network: one-year follow-up. Presented at: 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting; June 3-5, 2023; Chicago, IL. Abstract 6516. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.6516

2. Reed M, Przespolewski E, Doughty Walsh M, Amsler M, et al. Survey of biosimilar adoption across oncology pharmacy practices. Presented at: 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting; June 3-5, 2023; Chicago, IL. Abstract e188813. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.e18813