- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Addressing Disparities in Cancer Care and Beyond: What Can Be Done Now?

When the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) updated its policy statement on cancer disparities and health equity a year ago, 11 years had passed since the organization’s first statement on the differences in health care access, quality, and outcomes among patients of different races with cancer.1,2 The topic had become more timely in light of the inequity seen in COVID-19 mortality rates,3 ongoing disparities in cancer care and outcomes,4 and other health metrics such as insurance status.5 Over the past year, the major oncology and hematology organizations—ASCO1, the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC),6 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,7 the American Society of Hematology,8 and the Community Oncology Alliance9—have issued statements, launched initiatives, or devoted portions of their national meetings to the issue of disparities in cancer care.1,6-9

The ASCO authors concluded in 2020 that the time had come for less talk and more action “to overcome historical momentum and existing social structures responsible for disparate cancer outcomes,” and they put forth an action plan to improve diversity in hiring, clinical trials, access to care, and achieving “measurable and timely action toward achieving cancer health equity for all.”1

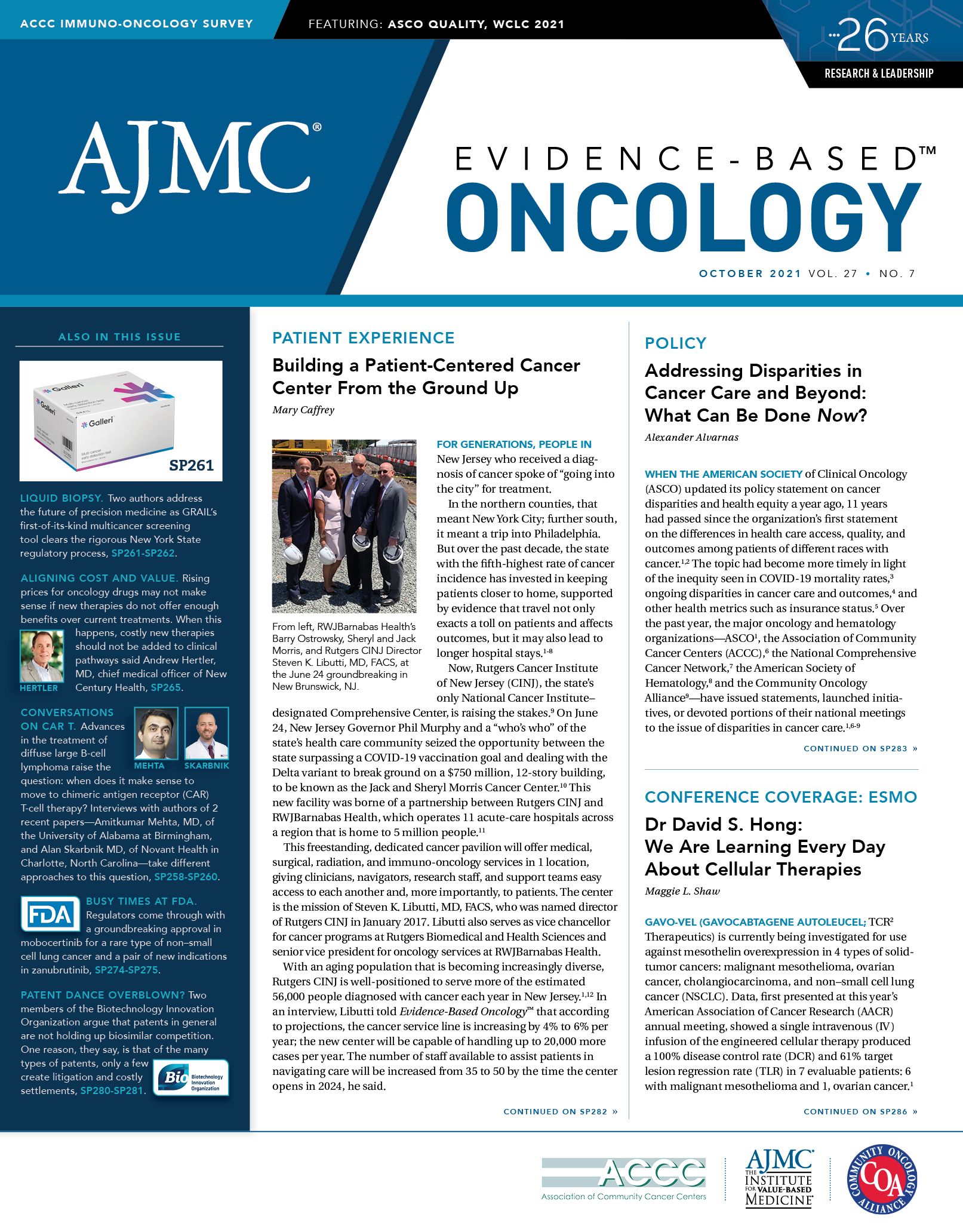

Pierce

In an article published ahead of her presidential address during the ASCO annual meeting in June, then–ASCO President Lori Pierce, MD, FASTRO, FASCO, discussed the organization’s commitment to Black patients with cancer, for whom inequities are especially glaring. In the United States, Black patients represent 15% of the cancer patient population, but they account for 4% to 6% of the enrollees in clinical trials.10 Black patients are 1.5 times more likely to be uninsured than White patients; only 3% of oncologists are Black, even though Black individuals make up 13% of the US population.1

As a result, Pierce noted in a 2020 essay, “progress in cancer prevention, detection, and treatment has reduced overall mortality in the United States, but that progress has not been enjoyed by everyone. Poorer outcomes persist in Black men and women, in rural populations, and in patients with lower income and education.”10

In addition, only 6% of US oncologists identify as Hispanic and few health investigators identify as non-White.1 Unlike non-Hispanic White individuals, for whom heart disease is the leading cause of death, cancer is the leading cause of death among Hispanic individuals.11

All of this points to the need to reduce disparities, and quickly. But how? The ASCO authors found plenty of inertia in health care. Evidence-Based Oncology™ gathered input from a group of health care leaders, from within and beyond the cancer community, and asked: How can we cancer disparities be reduced now? Specifically, the leaders were asked to discuss ideas that could be put into action in a 2-year time frame.

RANDALL A. OYER, MD

Medical Director, Oncology Program, Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Former President, Association of Community Cancer Centers

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Use antibias training to ensure patients are invited to clinical trials

Oyer

Randall A. Oyer, MD, discussed the need for more equitable clinical trials, a major initiative of ACCC. “Clinical trials are an indicator of quality of care,” he said. “Not all people have benefited to the same extent from the advances that have been made in cancer care in the United States. Health equity requires us to address the institutional racism and other failings that still exist [and their effect on populations].”

To begin to address these issues, Oyer said, “we need to get clinical trials out to where people live in the community.” First, this requires showing community practices how trials are set up and what personnel and resources are needed, Oyer said. Second, a near-term intervention would be to ensure that a broader group of patients are asked to take part in clinical trials, he said. “There’s still a lot of bias that’s involved in offering or not offering patients clinical trials, and we need to get training programs into the community to make sure that people understand their biases, so that we can mitigate those biases so that everyone is offered the opportunity to participate.”

A recent study found the most common reason patients don’t participate in a cancer clinical is because they are not asked, Oyer said.12 “If you ask a White patient, or you ask a Black patient, they both sign up, basically, to the same extent, if they’re offered the opportunity to do so.’’12

In addition to these interventions, Oyer emphasized the need to “understand the social determinants of health and how they affect a patient’s health over their lifespan. [This includes] what kind of food, exercise, environment they live in, what kind of education for self-care, what kind of resources they have to access health care.”

TODD M. SACHS, MD

Chief Medical Officer, AccessHope,

Duarte, California

Reduce disparities by leveraging lessons of telemedicine

Sachs

AccessHope is a program that allows patients and community oncologists to tap into the expertise of City of Hope, often through electronic sharing of records so the patient does not have to travel.13 Todd M. Sachs, MD, called for increased education within the care delivery system, especially for patients. “That means getting out to various people where they live, where they work, where they spend their time,” he explained.

The increased use of telemedicine could also reduce disparities—COVID-19 revealed the potential for technology, Sachs noted. “We started to get to where people live, where they are,” he said.

Since the pandemic began, hospitals have developed better protocols to ensure safety, Sachs said, but the risk is that the advantages seen with telemedicine could be lost. “I don’t want us to lose all that we gained by using telemedicine,” he said.

With AccessHope, “we’re providing this high level of expertise and knowledge from physicians in Los Angeles to people who may not live in Los Angeles proper, who may live in South Dakota in a very rural area, or in Kansas in a rural area and are not able to be treated at a national cancer institute,” he said.

Technology is also important for sharing information and key to improving quality, another way to reduce disparities in cancer care. “Cancer is different. In the world of cancer, there’s so much change for the better,” Sachs said. “New treatments, new therapies, new protocols, new research—if you’re an oncologist today and you’re trying to remember and learn and read all of those changes for over 100 types of cancer, it’s too hard to do.”

Finally, he said, “we need people to go in and get their preventive care. That would be a big win, and that can happen, ASAP. We don’t have to wait 2 years for that.”

H. JACK WEST, MD

Clinical Executive Director, AccessHope

Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics

Research, City of Hope

Duarte, California

Level the playing field to reduce variability in cancer care

West

Similarly, H. Jack West, MD, called for bringing more specialized access to more patients. West, a lung cancer specialist, said he founded the Global Resource for Advancing Cancer Education (GRACE) with the intention of being able “to help close the gap between the best care that’s available for some people and what people actually get.” GRACE was created in response to issues with quality of care outside academic settings. “There is an unfortunate shortfall and inequity in the broader community; it’s just quite variable. Not to say that there aren’t general oncologists who do a sensational job, but it’s really hard to keep up with everything that happens, especially in the past 5 or 10 years.”

The volume of data being published and the pace of advances in care have escalated to the point, “where it’s not feasible to expect one doctor, any doctor, to know everything that’s out there or even enough to necessarily be strongly competent in a broad range of oncology,” he said. West’s mission is to “level the playing field and make it possible for people who don’t have access to a specialist to borrow their expertise on demand by uploading it free for everybody.”

An additional benefit of GRACE is that it allows information to be democratized by enabling patients to be educated about their condition. West described it this way: “If I had a conversation with a patient that would be great for the patient, it would just evaporate into the room. But if I uploaded the information that I shared with them and made it available to people through a blog, anybody anywhere could access it—and it wasn’t any more work for me, but maybe it would help them have a conversation with their doctor.”

The idea, he continued, is this: “As long as 1 person in that exam room knows the best treatment, that’s fine—even if that’s the patient.”

Patient education is important, West said, but it can’t consume all of a physician’s time. West emphasized, however, that “if you make that information available to patients, they can be unbelievably laserlike-focused on finding the best information available anywhere.”

RUBEN MESA, MD

Executive Director, Mays Cancer Center

UT Health San Antonio MD Anderson Cancer Center

San Antonio, Texas

Include the family health expert in all key discussions

Mesa

Mesa emphasized the importance of working to achieve more effective and equitable clinical trial access as a means of improving health care access and quality. He brought attention to the need for inclusive research. “The key goal is, do the innovations going on in your clinical trials reflect the people in your city and region, I mean—the people you’re serving? We all recognize that there’s tremendous diversity within diversity.”

In addition to having representative demographics in a trial. Mesa also pointed out the need to understand the diversity found within diverse groups, stating, “We clearly have learned and are studying the great differences [among] even Latino populations. There are differences between individuals that have migrated from Mexico recently [and] individuals [who] are of Mexican heritage, but their families have been in the states for a long period of time; individuals from the Caribbean, people like me who are Cuban, [or individuals from] South America. So, there’s a lot of diversity, and there’s diversity as it relates to genetics, culture, and other parts.”

Those who run clinical trials must also address “logistics, access, sometimes transportation, sometimes other barriers,” he said. “The intensity of participating in the trial, in terms of time away from work” can affect who ends up participating, Mesa explained. If the trial schedule “makes it much more difficult to be able to either leave work, to be allowed to leave work, or to not paid for leaving work, that can really influence things,” he said.

Another focus of Mesa’s is improving health literacy and trust in patient communities. One method Mesa said has been helpful with patients with cancer in south Texas is to include the family health expert in key discussions. This could be a family member employed in health care, anyone “from a phlebotomist at a local hospital to a pharmacy technician at CVS, or a physician or a nurse,” he said. This is a person the family trusts to discuss treatment options, including clinical trials.

SACHIN H. JAIN, MD, MBA, FACP

President and CEO, SCAN Group and SCAN Health Plan

Long Beach, California

Uncover barriers to care and underlying causes to health issues

Jain

Sachin H. Jain, MD, MBA, FACP, is a pioneer at finding the root causes of why individuals use too much unnecessary health care—such as hospitalizations—and coming up with better ways to pay for care individuals really need. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, when he worked for CareMore, Jain created programs to treat loneliness as a health issue.14

These days, he’s taking on homelessness by working on a payment model to address a crisis that has exploded in California,15 where he’s has been based since 2015.

“We have a lot of unnecessary health care utilization that’s driven by poorly managed chronic disease. And if you actually apply that frame to multiple different populations, you find key areas where you can improve health care outcomes and reduce overall health care spending and utilization,” Jain said. “That’s why we look at things like homelessness, and we ask ‘What is the underlying issue there that we can address and leverage to reduce overall health care costs and improve health care outcomes for patients?’”

By addressing these social determinants, Jain argues, we can potentially “contract the hospital sector. Because ultimately, what we’re trying to do is make hospital care less necessary by better managing people’s conditions.”

Doing so requires moving away from a fee-for-service model. “We actually have lots of data on who the so-called rising-risk or high-risk patients are, but the capacity in the health care system to actually act on those high-risk or rising-risk patients is low because of how we pay for care—and because of how we actually structured and organized care delivery. Because we largely have a fee-for-service chassis, we mostly take care of people when they have problems, as opposed to paying significantly for upstream management and prevention.”

When asked how soon this move away from fee-for-service care delivery could be applied, Jain said, “I see medical groups in California—and, really, all over the country—that are starting to embrace this way of thinking about patient care. And they’re changing how they work as a result of changes and how they’ve decided to get paid by third-party payers.”

Jain warns that the transition brings a measure of risk. “There is an opportunity to simultaneously improve the quality of care, but there’s also potentially an erosion of the quality of care if we don’t manage that carefully,” he said.

Conclusion

Discussions with each expert confirmed that the United States still has a long way to go to achieve equity in health care. Hospitals, health care systems, and clinical trials have not fully addressed the historic barriers to access or the social factors that produce uneven outcomes. Yet, as the interviews showed, solutions are possible. Each one proposed ideas based on concrete and successful plans that have been implemented, including strategies the interviewees had used in their own fields.

Although the pandemic has raised the visibility of how unequally health care is delivered, it has also been a catalyst for many providers to offer increasingly creative solutions that more effectively address disparities. As such, it is important to seize this moment and move forward with a renewed sense of urgency so that the momentum can lead to effective and sustainable transformation of how care is delivered.

References

1. Patel MI, Lopez AM, Blackstock W. Cancer disparities and health equity: a policy statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(29):3429-3448. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.00642

2. Goss E, Lopez AM, Brown CL, Wollins DS, Brawley OW, Raghaven D. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: disparities in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2881-2885. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1680

3. Health disparities. Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). CDC. Updated September 29, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.htm

4. Balogun OD, Bea VJ, Phillips E. Disparities in cancer outcomes due to COVID-19-a tale of 2 cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(10):1531-1532. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327

5. Artiga S, Hill L, Orgera K, Damico A. Health coverage by race and ethnicity, 2010-2019. Kaiser Family Foundation. July 16, 2021. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/

6. Association of Community Cancer Centers launches institute to diversify cancer clinical trials. ACCC. News release. June 3, 2021. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://www.accc-cancer.org/home/news-media/press-releases/news-template/2021/06/04/association-of-community-cancer-centers-launches-institute-to-diversify-cancer-clinical-trials

7. Elevating cancer equity: recommendations to reduce racial disparities in guideline adherent cancer care. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. February 22, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/docs/default-source/oncology-policy-program/2021_elevating_

cancer_equity_webinar_slides.pdf?sfvrsn=e11f66e4_2

8. Flowers CR, Donald CE. A look into ASH’s diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. The Hematologist. 2021;18(2). February 19, 2021. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://ashpublications.org/thehematologist/article/475281/A-Look-Into-ASH-s-Diversity-Equity-and-Inclusion

9. Community Oncology Alliance. COA disparities in cancer care position statement. April 30, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://communityoncology.org/coa-disparities-in-cancer-care-position-statement/

10. Pierce L. ASCO’s commitment to addressing equity, diversity and

inclusion of Black cancer patients and survivors. JCO Oncol Pract.

2021;17(5):255-257. doi:10.1200/OP.21.00257

11. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018-2020. Atlanta; American Cancer Society, 2018.

12. Alhajji M, Bass SB, Nicholson A, et al. Comparing perceptions and decisional conflict towards participation in cancer clinical trials among African American patients who have and have not participated. J Cancer Educ. Published online July 11, 2020. doi:10.1007/s13187-020-01827-w

13. Caffrey M, Levine H. Reimagining cancer care delivery-and serving employers-

through AccessHope. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(SP10):SP365-

SP366. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.88558

14. Caruso R. CareMore’s Togetherness program addresses a symptom of living with chronic illness: loneliness. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(SP10):SP442.

15. Jain SH. Homelessness is a healthcare issue. Why don’t we treat it as one? Forbes. April 17, 2021. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sachinjain/2021/04/17/homelessness-is-a-healthcare-issuewhy-dont-we-treat-it-as-one/?sh=4c9dfcd777e3

Lymphoma Research Foundation CEO on Biden’s Cancer Moonshot, Financial Toxicity

February 3rd 2022On this episode of Managed Care Cast, we speak with Meghan Gutierrez, CEO of the Lymphoma Research Foundation, about financial toxicity, how the pandemic has affected patients’ financial needs when they have cancer, health care disparities and care gaps, and more.

Listen

Keeping Patients With Cancer Out of the ED Through Dedicated Urgent Care

October 13th 2021On this episode of Managed Care Cast, we bring you an interview conducted by the editorial director of OncLive® who talks with the advance practice provider chief at Winship Cancer Institute about how having a dedicated cancer urgent care center will make cancer treatment plans seamless whil helping patients avoid exposure to infectious diseases in emergency department waiting rooms.

Listen

From Red Tape to Relief: Rewriting the Rules of Prior Authorization

June 23rd 2025Up to 257 million Americans could benefit from these prior authorization reforms that could have cross-market implications on health care plans administered through commercial insurers, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid.

Read More