- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Thoughts on Redesigning Health Care: Aligning Incentives to Drive Innovation

An editorial in response to the editor-in-chief’s December 2021 letter describes how a payer continues to push the limits of innovation through shared learnings and collaboration.

Am J Accountable Care. 2022;10(1):5-7. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajac.2022.88846

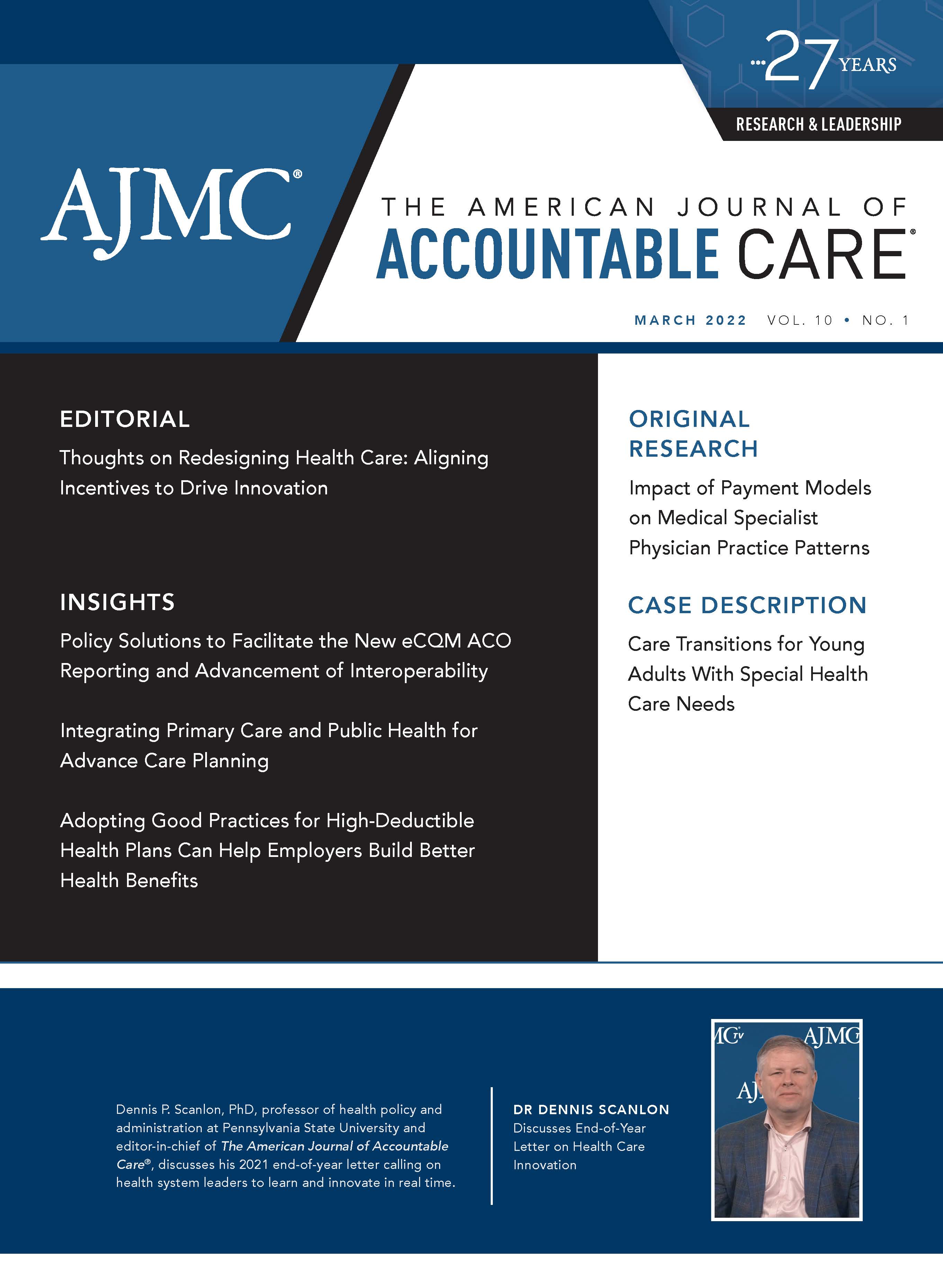

In the December 2021 issue of The American Journal of Accountable Care® (AJAC), Editor-in-Chief Dennis P. Scanlon, PhD, authored a letter calling on health systems to innovate and learn in real time with the goal of delivering patient-centered care. He then invited organizational leaders to respond in editorials of their own, which will be published in AJAC throughout 2022.

Health care has drifted far from its roots. The trusted, dedicated physician making house calls to patients stopped doing so more than a half-century ago. Patients would see the same neighborhood doctor for years, relying on that relationship and the physician’s higher education and training to make them feel taken care of and cared for. Back then, given the limited possible treatments, most physicians’ knowledge of medicine resided in their heads.

With the advent of increasingly complex technologies (like those of a modern intensive care unit) and the growing volume of scientific knowledge, change became inevitable. We as physicians increasingly subspecialized as one way to manage the flood of new information. We began using innovative and expensive technologies as diagnostic and therapeutic aids, and as a result it became necessary for patients to come to doctors rather than us going to them. What had been a craft-based industry was transformed by technology.

Today, the doubling of medical knowledge is measured in weeks to months, and treatment options even among subspecialists are so numerous that no single individual, no matter how well trained, could possibly remember—much less optimize—the information available. And so we have standard orders, expected practices, and guidelines to help even the subspecialized clinician manage the overwhelming and ever-growing streams of data and information. And because the incentives designed for a previous age no longer serve us, as physicians we find ourselves on a never-ending treadmill of patients scheduled in 10- to 15-minute blocks with no time left to connect on a personal level. Fee-for-service (FFS) payment models drive these behaviors. Yet this model has robbed us of our connection to our patients—the primary source of meaning in our work.

I know I’m preaching to the choir, but reminders are important lest we lose sight of our true purpose. We exist to serve individuals, often in their time of greatest need—to alleviate suffering, to treat and cure disease when possible, and to care and comfort when it is not possible to cure.

One of the most obvious examples of the power of incentives is in collaborative models between payers and the delivery system. To achieve this aim, we at Banner|Aetna have taken the strategy of joint venture. In this model, delivery system and payer become co-owners of the plan and have the same vested interest in success. In our case, Aetna does what it does best, analyzing and administering the predictive modeling, providing a ready source of out-of-area coverage through its national network, and initially providing the programs that support out-of-hospital care management and comprehensive utilization management. Banner Health provides its expertise in the delivery of evidence-based care to individuals and the populations served. We also agreed that over time, where possible, we would push outpatient care management and utilization management (UM) services over to the delivery system. The notion is that these services would best be owned and operated by Banner Health, by the doctors and administrators with a deep understanding of patient care needs and preferences in local markets. Finally, because we can pool the resources of Banner, Aetna, and now CVS Health, we gain access to resources, ideas, and innovations in all 3 organizations.

In short, Banner Health also has a financial stake in the game, which is where the alignment of incentives comes into play. Banner Health has significantly grown its insurance operations over the years and serves more than 310,000 Medicare/Medicaid plan members. Now its providers are uniquely positioned and motivated to support Banner|Aetna members, because their employer is literally part of this organization, financially, operationally, and clinically. It’s not enough for a health system to structure itself to simply support insurance carriers and their new models. In many of these models, including certain patient-centered medical homes and bundled payment models, you still have the push-pull of FFS between carrier and provider instead of the genuine collaboration that takes place in a joint venture. That’s where organizations like Banner Health and Aetna are really leading the charge toward value vs volume.

Of course, financial incentives are just one key piece of the puzzle. In order to achieve its financial goals—while also improving member health—our organization needed to actually improve quality and outcomes for at-risk members. One avenue we explored in doing so was the development of our multidisciplinary care teams (MDCTs) for patients with serious chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, or heart disease. Patients with these diagnoses at the highest risk constitute 5% of our member population while accounting for roughly 50% of overall health care costs.

The MDCT is intensely patient focused and can offer in-home assessments that provide an understanding of family dynamics and barriers to care. The team can go the extra mile to, for example, do hands-on and in-person teaching. The dietitian might go grocery shopping with a member to help them understand what makes a good meal plan or attend a clinical appointment with the patient to help explain the results of the visit and the expectations of the care team and how that will support the patient’s goals. We also provide a fund dedicated to addressing social and financial barriers to care.

The wraparound approach was studied internally under the design guidance of our colleagues at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. We found through our own experience that although there was a significant increase in utilization of psychiatric and behavioral health services, cost reduction trends exceeded $900 per member per month, representing net savings even after accounting for program costs (Aetna Clinical Analytics, unpublished internal document, 2018). The clear driver of savings was a significant reduction in hospitalizations.

In March 2021, Banner Health took over staffing and operation of the model from the health plan. The transition resulted in yet another improvement. The model had already been shown to be highly engaging. We found that when the MDCT reached out to these vulnerable members, 25% to 30% of those attempts resulted in both successful contact and the implementation of at least 1 element of a care plan (well above typical engagement numbers for traditional payer models). After the move to Banner Health, engagement by the same measure rose to more than 60% in a matter of months.

We have also demonstrated in our model that UM services can be provided by the delivery system without any decrement in performance. Today, about half of all UM decisions such as prior authorization and concurrent review are made by Banner Health nurses and physicians.

Incentivizing collaboration over competition also may result in health systems embracing disruptive technologies sooner. For example, when I first heard the term “reversal” applied to diabetes a few years ago, I immediately dismissed such a claim as too good to be true.

Yet published peer-reviewed clinical trial results from Virta Health, a company offering a diabetes management app, showed that large numbers of users successfully lowered their glycated hemoglobin A1c levels below the diagnostic threshold for type 2 diabetes while simultaneously stopping most, if not all, of their diabetes-specific prescribed medications. All this was accomplished over the course of a year, with more than 80% of participants choosing to remain in the study for the entire measurement period. How was this possible?

The Virta Health model marries technology with the sciences of metabolic disease and human behavior. Coining the term continuous remote care, the app connects patients to a care team through 2-way communication (via text, voice, or email) up to several times a day. The app also enables the exchange and tracking of key biometric markers that inform the care team’s decisions, including designing a nutritionally complete, low-carb diet customized daily for individual goals, health status, food allergies, and preferences such as veganism or other lifestyle choices. This intensely focused app, coupled with advice in real time, functions as a 24/7 care team in a patient’s pocket, making it easier for them to maintain a healthy diet and exercise regimen and for any of their concerns to be addressed. Although no solution works for everyone, the app is a tech-enabled model centered around connection, caring, and the patient’s needs.

Armed with these data, and with successes from Banner|Aetna patients who piloted the app, it was relatively easy to convince my colleagues to contract with Virta Health and offer the app to members with type 2 diabetes at no additional cost to them or their employers. Although this involves a large up-front investment for the joint venture, if participating members experience similar reversals as detailed in the study, we will realize huge long-term savings and the patients will lead healthier, longer lives. Given that it costs twice as much to treat patients with diabetes, some health insurers will opt to cover the cost of such a program, but only a joint venture like Banner|Aetna enjoys the luxury of trying promising care solutions without threatening the existence of either entity.

Of course, we have only scratched the surface of what is possible. Banner|Aetna will continue to push the limits of innovation through our shared learnings and collaboration. When we find scalable solutions that work, we will share those with our partners at Banner Health, Aetna, and CVS Health on a multistate and national level. In this way, we serve as an innovation laboratory for our parent organizations and the country. Because we are small and nimble with the backing of these progressive companies, we can quickly model value-based solutions that put patients first.

Author Affiliation: Executive vice president and chief medical officer at Banner|Aetna.

Source of Funding: None.

Author Disclosures: Dr Groves works on the Virta Health program for prediabetes in the initial pilot group for Banner|Aetna; the only financial benefit is that engagement of members leads to lower cost and better health.

The forward-looking statements in this piece are not guarantees, and they involve risks, uncertainties, and assumptions. Although we make such statements based on assumptions that we believe to be reasonable, there can be no assurance that actual results will not differ from those expressed in the forward-looking statements.

Authorship Information: Concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Send Correspondence to: Robert Groves, MD, Banner|Aetna, 4500 E Cotton Center Blvd, Phoenix, AZ 85040. Email: GrovesR@banneraetna.com.