- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

The Carrot or the Stick? Integrating Palliative Care Into Oncology Practice

As cancer care moves to payment focused on improving value, payers are more often using regulation and incentive to improve the integration of palliative care into oncology practice.

In an era with increased emphasis on bending the cost curve while increasing availability of targeted therapies for those with cancer, it can be difficult to strike the right balance between the art and the science of practicing high-quality oncology care. Perhaps just as difficult is the role of a regulating body or healthcare financer in providing the right incentives, policies, and authorization practices that allow clinical judgment while ensuring treatments are of high quality, evidence-based, and align with patient preferences. As cancer interventions become more effective and more complex, it is essential to create guardrails and incentives so that high-quality, patient-centered, cost-effective healthcare continues to be delivered.

Integrating palliative care into a treatment plan, preferably at the point of diagnosis, is crucial to delivering high-quality cancer care. Palliative care—which focuses on relieving the pain, symptoms, and stresses of a serious illness—has the ability to change the delivery and experience of healthcare for patients and caregivers. Many prospective studies have shown that when integrated early in the treatment process, palliative care is associated with an increase in quality of life, satisfaction with care, an improvement in symptom burden for both patients and caregivers,1-3 and longer survival.2 While the evidence for palliative care has been compelling, the integration of palliative care into cancer care is moving slowly, requiring considerable changes in paradigm and ideology for oncologists as well as shifts in process flows for their practices. As financing for cancer care begins to shift from fee-for-service (FFS) to value-based payments, payers have an opportunity to incentivize and regulate services provided to patients and their families that can support oncology teams to provide high-quality care transitions for cancer patients in any stage of disease—from point of diagnosis, through treatment, and nearing end of life or survivorship.

Current State of Cancer Care

Economist Michael Porter defines value in healthcare as “patient health outcomes achieved per dollar spent,” emphasizing that the health outcomes achieved should focus on the patient’s preferences and defined measures for success, rather than strictly clinical effectiveness of treatment or survival rate.4 FFS cancer care does not factor in the quality of care provided and largely emphasizes impetus towards providing costlier and more aggressive services, thereby straining the healthcare system with the cost of experimental and targeted therapies and increasing the exposure of financial toxicity on patients and caregivers. Often, these treatments are in direct opposition to patient preferences.5 Even with health insurance, 10% of Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental insurance have been found to spend over 60% of their annual income on out-of-pocket expenses following cancer diagnosis.6 Twenty-five percent of participants in a Kaiser Family Foundation study reported using all or most of their savings dealing with cancer, while 33% of families reported a problem paying their cancer-care bills.7

Despite the variability in quality of care and financial impact on patients and caregivers, advances in treatment and precision medicine have increased the number of cancer survivors in the United States.8 With growing urgency to balance the delivery of high-quality cancer care with costs, stakeholders—including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI)—are developing new financial and clinical models that emphasize value.

Earlier Attempts at Practice Transformation

When moving from clinical-imputed value of treatment to the patient-perceived value of cancer care, it is imperative to include additional domains to determine the overall value of a test, procedure, or treatment. Suffering in cancer patients can be derived from multiple factors, including uncontrolled symptoms, inadequate psychosocial support, financial toxicity, inadequate understanding of prognosis or treatment options, disregard for patient preferences for treatment or setting, or even prolongation of the dying process in terminal cases. In 2012, in an effort to mitigate this, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched, as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign, the top 5 list of tests and procedures in oncology care that should be questioned due to their failure to add further clinical value to the course of cancer treatment for a patient. The list was compiled with input from more than 200 oncologists and was used to promote communication among oncologists about best practices in delivering higher-value care. With 2 procedures highlighting improper management of pain and symptoms under Choosing Wisely, one recommendation from ASCO was earlier integration of palliative care into the treatment plan for those patients with advanced cancer.9

In a retrospective review of this list and of adherence to the Choosing Wisely recommendations, it was found that not only was adherence highly variable, but that aggressive care did not decrease following implementation of these recommendations. Overall adherence to these measures ranged from 53% to 78%, with adherence being poorest for patients diagnosed with advanced cancers. With the palliative care measure in particular, adherence ranged from 60% at 90 days from the date of death to 89% at 14 days from the date of death.10 These results indicate that early integration of palliative care into cancer care is largely nonexistent, with referrals to hospice or palliative care coming consistently only in the last 2 weeks of life. This late-stage integration does not allow a patient or caregiver to experience the full effect of palliative care’s ability to alleviate suffering throughout the care continuum, and it suggests that aggressive, often unwanted, therapy is occurring until the patient is very near death.

Often overlooked as a hurdle to the integration of palliative care into cancer care is that graduate medical education includes only limited training in communication skills and care coordination. This training often does not continue once a new doctor selects a specialty, such as oncology. A considerable amount of evidence suggests that communication skills training in oncology practice has the ability to help healthcare professionals demonstrate feelings of empathy, address stressful and difficult situations, improve care transitions, and improve the quality of medical care and satisfaction for patients and families.11 However, the receipt of such training is dependent upon the interest and initial comfort level of an oncologist to pursue and continue such training on their own time, as part of continuing medical education. This results in a workforce that is highly variable in its ability to communicate with patients and families about prognosis, treatment goals, or the clinical value of cancer treatment being administered.

Practice transformation is also limited by the variability in quantifiable process and outcome measures being used by all value-based purchasing programs, including those for cancer care. In a review of 129 publicly available value-based purchasing programs, the Rand Institute found that there is a high degree of variability in measures chosen for clinical appropriateness of care, patient preferences and satisfaction, and care centered on patient functional status.12 The high level of experimentation in the area of value-based purchasing and bundled payments has generated mixed results on the effectiveness of these types of programs, further increasing the hesitance of providers to transform their practices to achieve stipulated targets. Among those successful programs, the elements determined to improve clinical outcomes included considerable financial incentives and alignment on quality, utilization, and performance targets, as well as provider training, engagement, and support for quality improvement initiatives and reporting requirements in the electronic health record (EHR).12

Blending Incentives and Support to Integrate Palliative Care Into Oncology Practice

The practice of integrating palliative care into oncology practice has been gaining considerable traction with the implementation of bundled payment programs for oncology and the introduction of the Oncology Medical Home (OMH) model.13 Most notable is the implementation of the Oncology Care Model (OCM) by CMMI, a demonstration project focused on improving the value of cancer care for Medicare beneficiaries. OCM and multiple other oncology bundled payment models being piloted throughout the country focus on the use of incentives and reporting criteria to align patients undergoing active cancer treatment to evidence-based pathways and additional support for care coordination. Performance is measured using cost, quality, and patient satisfaction targets.

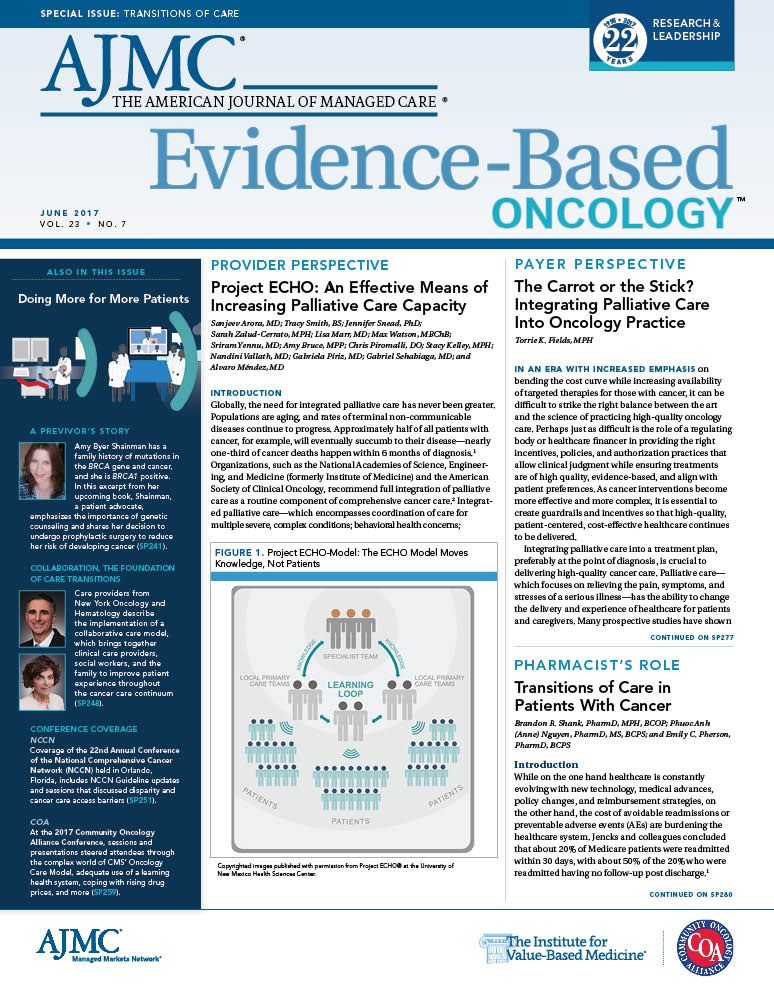

Bundled payment programs for oncology, including OCM and OMH, require practice transformation (Figure).14,15 While these requirements may be possible to achieve by a larger oncology practice with considerable operational infrastructure and support, independent oncologists and smaller practices may have more difficulty implementing change. Because palliative care teams are focused on providing a team-based approach to care, care coordination, and a multi-dimensional care plan documenting treatment preferences, the integration of palliative care or a partnership with a palliative care team can be used to facilitate practice transformation and provide a higher degree of patient-centered care.16

In addition to bundled payment reimbursement for providing oncology care, payers are experimenting with additional incentives and regulatory criteria to better integrate palliative care into oncology beginning at point of diagnosis. Incentives and regulation range from more standard approaches under value-based purchasing to those that are more innovative in nature, all with considerations that must be weighed prior to implementation.

One standard approach to incentivizing the integration of palliative care into oncology practice is the additional ability for oncology practices to achieve a higher percentage of shared savings or provider performance bonuses based on specific process and quality targets, focusing on this integration. For example, a proposed process measure by which to increase an incentive payout would be the documentation of a medical surrogate for all patients diagnosed with cancer or the documentation of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status, both of which are indicators of, or drivers for, early palliative care intervention. An example of a quality outcome measure would be the hospice referral rate or median length of stay (LOS) on hospice for patients with metastatic cancer. By incentivizing the median LOS on hospice, oncologists would need to engage the patient early and often regarding treatment preferences, including preferred place of death. Payers and providers alike must be cautious in measure selection, as not all patients will prefer hospice or wish to die at home, and this must be taken into account in reporting and calculation of incentive payouts.

Other approaches that have been proposed include additional reimbursement for palliative care, including bundled payments specifically for palliative care services that would align but not compete with the bundled payment for oncology. This approach allows for the oncologist and patient to receive an extra layer of support that focuses on pain and symptom management but does not compete with the payment made to the oncologist for care being provided. Models that embed or integrate a palliative care practitioner or team are most successful when incentives and outcomes are aligned and work together to minimize the impact of multiple providers and appointments on the patient and family undergoing treatment. Continuity and coordination of care should be at the center of treatment, with both the palliative care and oncology team remaining involved throughout the course of the disease, including through death. Some proposed payment methods reinforce this idea by continuing bundled payment reimbursement for the oncologist as the patient transitions to hospice. However, this is not ideal in practice transformation, as the goal of integrating palliative care into oncology practice is to ensure that all clinicians on the patient care team are operating at the top of their license. Continuing to have active management of the patient by an oncologist while the patient elects hospice does not encourage the best use of resources, but it is highly encouraged that the oncologist continues as part of the care team, monitoring and engaging with the patient even after hospice election.

As evidenced from the mixed results on the impact of value- based purchasing on clinical outcomes, financers and regulators of healthcare cannot depend solely on incentives, financial or otherwise, to transform clinical practice. To ensure that patients and families can receive high-quality care while being protected from unwanted medical treatment and financial toxicity, safeguards must be put in place to assist clinicians in making evidence-based decisions that align with the goals and preferences of patients with cancer and their caregivers. A majority of regulatory approaches proposed by payers to maintain value in cancer care and reduce the variability of care that is delivered are focused on the alignment of treatment protocols with evidence-based pathways as designated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s Clinical Practice Guidelines. However, adherence to these guidelines does not outwardly encourage integration of palliative care into cancer care and often restricts providers from feeling like they can continue practicing the art of medicine.

One way to support providers in making decisions considering multiple domains of the patient’s care is through early and regular integration of palliative care into clinical treatment. Payers implementing an FFS or bundled payment model for oncology treatment often have prior authorization requirements. Integrating palliative care consultation requirement prior to authorization of any form of cancer treatment can ensure that the patient and caregiver remain at the center of the treatment plan, that they understand the prognosis and treatment options, and that they have documented goals of care. This is evidenced by studies showing that just the first palliative care consultation, in either an inpatient or outpatient setting, resulted in patients reporting an improved quality of life, improved satisfaction with the treatment plan and provider, improvement in physical and psychological symptoms, and reduction in financial toxicity.3,17 In addition, payers can require shared decision-making documentation and ongoing documentation of palliative care consultations at different points during treatment, including when a change is made in a treatment plan, upon beginning subsequent treatment, or following a cancer-related inpatient admission.

Other regulations that will further reinforce the integration of palliative care into oncology practice include the requirement for additional documentation in the patient’s EHR and the requirement of a care coordinator responsible for treatment team communication and care transitions. Both these criteria are requirements under the OCM and under many other OMH models being piloted. Areas necessary to be captured by the EHR include documentation of: the patient’s medical surrogate; the goals of care using a standardized assessment; and advance care planning documents, including an advanced directive and a Physician Order for Life Sustaining Treatment, where appropriate. Documentation of patient preferences and goals of care, as well as the implementation of a team-based approach to cancer care, become imperative with the intense needs of patients and caregivers facing a cancer diagnosis and the increasing complexity and cost of cancer care.

Conclusion

Undergoing practice transformation, including the integration of palliative care into oncology practice, is no small feat. It takes more than financial incentives and outcomes measures, including increased provider education, training, and support, for change to occur and be sustained over time. While regulations for oncology practice increase in an attempt to bend the cost curve and improve quality, palliative care can provide an extra layer of support for the patient and the provider alike, injecting the art of practice that keeps the patient at the center of care.AUTHOR INFORMATION

Torrie K. Fields, MPH, is senior program manager, Palliative Care, Blue Shield of California.

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE

Torrie K. Fields, MPH

50 Beale Street B21-253

San Francisco, CA 94105

E-mail: Torrie.Fields@blueshieldca.comREFERENCES

1. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(13)62416-2.

2. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic nonsmall- cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678.

3. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(1):75-86. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000108.

4. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMp1011024.

5. Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, Palmer L, Benisch-Tolley S. Patient preferences versus physician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2883-2885.

6. Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer [published online November 23, 2016]. JAMA Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1001/ jamaoncol.2016.4865.

7. USA Today/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health National Survey of Households Affected by Cancer. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/health-costs/ poll-finding/usa-todaykaiser-family-foundationharvard-school-of-public-2/. Published November 1, 2006. Accessed January 16, 2017.

8. Cancer treatment & survivorship: facts & figures, 2014-2015. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/ cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship- facts-and-figures-2014-2015.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed April 30, 2017.

9. Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: the top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1715-1724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8375.

10. Ramsey SD, Fedorenko C, Chauhan R, et al. Baseline estimates of adherence to American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Board of Internal Medicine Choosing Wisely initiative among patients with cancer enrolled with a large regional commercial health insurer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(4):338-343. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002717.

11. Barth J, Lannen P. Efficacy of communication skills training courses in oncology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(5):1030-1040. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq441.

12. Damberg CL, Sorbero ME, Lovejoy SL, Martsolf GR, Raaen L, Mandel D. Measuring success in health care value-based purchasing programs: findings from an environmental scan, literature review, and expert panel discussions. Rand Health Q. 2014;4(3):9. eCollection 2014.

13. Sprandio JD. Oncology patient-centered medical home. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(Suppl 3):47s-49s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000590.

14. Oncology care model. CMS website. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/. Updated April 7, 2017. Accessed April 30, 2017.

15. Waters TM, Webster JA, Stevens LA, et al. Community oncology medical homes: physician-driven change to improve patient care and reduce costs. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(6):462-467. doi: 10.1200/ JOP.2015.005256.

16. Newcomer LN, Gould B, Page RD, Donelan SA, Perkins M. Changing physician incentives for affordable, quality cancer care: results of an episode payment model. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):322- 326, doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001488.

17. Davis MP, Bruera E, Morganstern D. Early integration of palliative and supportive care in the cancer continuum: challenges and opportunities. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:144-150. doi: 10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.144. Review.

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More