- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

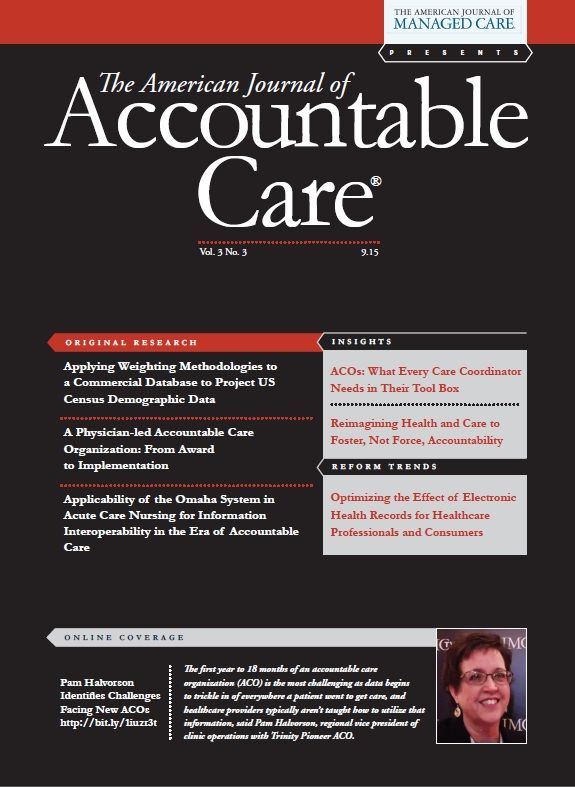

Reimagining Health and Care to Foster, Not Force, Accountability

It is time to bring health and caring to the forefront of healthcare and to empower accountability for all participants in the system.

The fatal flaws in our US healthcare system could at least partially be blamed on any participant: the government, providers, health insurers, patients, and caregivers. There are near limitless opportunities for improvement though, and as we move toward an “accountable care” care delivery and reimbursement model, the blame for system failures is expected to be shared more equally—primarily through new permutations of financial penalization for poor care quality and clinical outcome performance. However, we must consider if creating a more level playing field of blame among healthcare system participants is transformative, or is it just modifying the financial metrics that have little bearing on the ultimate quality of life of its patients? If you could design a healthcare system that supports both “health” and “care,” where would you start?

What Would You Teach in Medical School?

According to a 2013 JAMA study, what we eat has the highest impact on premature death and disease.1 So why don’t we teach nutrition in medical school? NPR reported in July 2015 that only about 25% of all US medical schools offer the National Academy of Sciences’ recommended 25 hours of nutritional training in their curriculum.2 If nutrition is the most important factor in health, yet we aren’t teaching it in medical school, how are we laying the foundation for an approach to medicine with a focus on establishing, maintaining, and improving health rather than merely fixating on illness?

Our current medical school system is designed to teach providers how to treat illnesses and injuries, rather than to educate patients on prevention. A transformative approach would emphasize teaching the fundamental principles of wellness, giving students a contextual understanding of the nonclinical factors influencing their patients’ health; and train them to collaborate with patients as equal participants in the care plan, making them equally accountable for success.

Partnering With the Community and Revamping Care Roles

In today’s healthcare system, the only care that “counts” is delivered in the clinical setting and constitutes a reimbursable event. However, common sense tells us the majority of care activities actually occur outside the clinical setting in patient homes and the community. Dr Kahlon of Dell Medical School believes extensive community involvement is the key to creating a “vital, inclusive health ecosystem,” which can address the full spectrum of health needs, with all participants engaging with shared accountability for individual and population health.3 Providers and insurers could partner with local contractors, for example, as described by Dr Olsen, to “end fuel poverty” in Britain.4 Similar partnership initiatives could be undertaken to install ramps for seniors to prevent falls, which typically precipitate health decline (and rapid healthcare cost increase).

The roles of nonclinician caregivers could also change to make care more readily available and efficient: pharmacists could recommend generic drugs and adjust medication dosages without involving a physician, emergency medical technicians (EMTs) could give flu shots, and unused EMT vehicles and personnel could be repurposed as mobile urgent care units for those without transportation.

Empowering Patients to Manage Their Health

Regardless of how well our healthcare providers are trained and how strong our community partnerships and support infrastructure may be, the ultimate accountability for managing an individual’s health lies with that individual—or their caregiver, if unable to materially participate in decisions. To be accountable, first one must be empowered, and empowerment starts with information; patients must have access to their complete medical records in order to make informed decisions about their health.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of patient advocates, this critical goal of healthcare transformation is becoming a reality. It’s time to bring health to the forefront of healthcare and to empower accountability for all participants in the system. Moreover, it’s time to care.Author Affiliation: Dell Healthcare & Life Sciences, St Augustine, FL.

Funding Source: None.

Author Disclosures: None.

Authorship Information: Manuscript concept, drafting, and revision.

Send correspondence to: Mandi Bishop, MA, Dell Healthcare & Life Sciences, Plano, TX. E-mail: mandi_bishop@dell.com.REFERENCES

1. US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-606.

2. Eng M. A dose of culinary medicine sends med students to the kitchen. NPR website. http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/07/01/419167750/a-dose-of-culinary-medicine-sends-med-students-to-the-kitchen. Published July 1, 2015. Accessed September 10, 2015.

3. Maninder Kahlon [bio]. University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School website. dellmedschool.utexas.edu/team-profile/mini-kahlon. Accessed September 10, 2015.

4. Olsen NDL. Prescribing warmer, healthier homes: British policy to improve homes should help both health and the environment. BMJ. 2001;322(7289):748-749.

Telehealth Intervention by Pharmacists Collaboratively Enhances Hypertension Management and Outcomes

January 7th 2026Patient interaction and enhanced support with clinical pharmacists significantly improved pass rates for a measure of controlling blood pressure compared with usual care.

Read More

HEDIS Glycemic Goal Achieved Using Control-IQ Technology

December 22nd 2025A greater proportion of patients with type 1 diabetes who used automated insulin delivery systems vs multiple daily injections achieved the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) glycemic measure.

Read More

Linking Data to Determine Risk for 30-Day Readmissions in Dementia

December 22nd 2025This study found that certain characteristics in linked electronic health record data across episodes of care can help identify patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias at high risk of 30-day readmissions.

Read More

Performance of 2-Stage Health-Related Social Needs Screening Using Area-Level Measures

December 19th 2025Limiting health-related social needs screening to lower-income areas would reduce screening burdens; however, this study found a 2-stage screening approach based on geography to be suboptimal.

Read More