- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

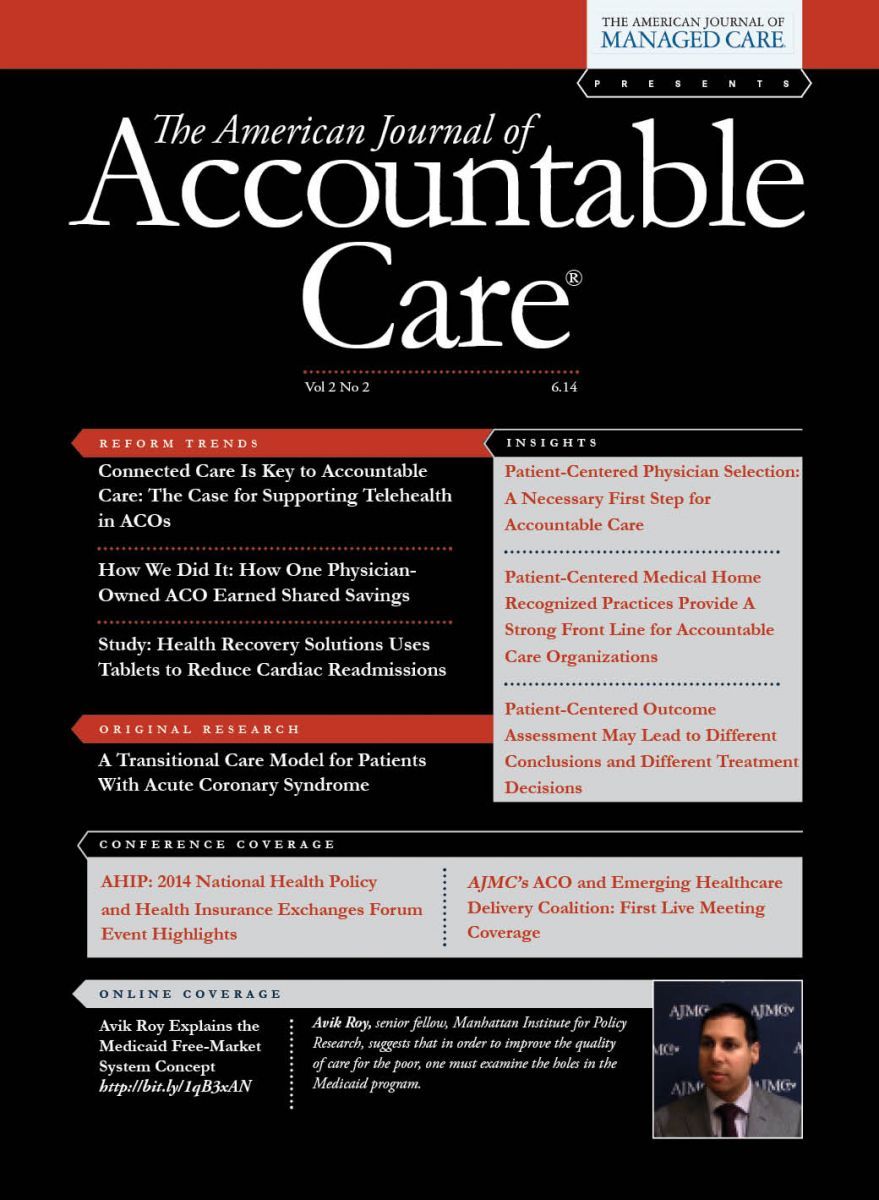

Patient-Centered Physician Selection: A Necessary First Step for Accountable Care

Improving attention paid to patient preferences when matching patients and physicians on the basis of value and quality rather than costs and outcomes can help a patient achieve the overall healthcare experience.

There is a notable gap in our system wide efforts to promote accountable, patient-centered care: physician selection. The past decade has borne witness to significant advances in reorienting the processes and experiences of care around patient preferences and values, but the same level of focus has not been directed to helping patients identify the best physician for their needs. Instead, our prevailing approaches to matching patients with physicians remain largely agnostic to variations in patient preferences, tethered to the traditions of peer recommendation and reputation-based referral. Even recent efforts to bring more transparency and consumer choice to healthcare decisions focus primarily on costs and outcomes,1 and neglect other domains of the patient experience.

This eschews a growing understanding of the divergent priorities many patients have when selecting a physician. Some patients place a premium on clinical reputation and technological advancement, while others are concerned more with measures of quality and value. These preferences are layered on top of additional dimensions as varied as communication style and cultural appropriateness.

Appreciating and acting on this heterogeneity is essential to improving patient ability to interact with the system and identify clinicians that best fit their needs and preferences. Strengthening the attention to patient preferences in this critical first step of a patient’s healthcare experience is critical if patients are going to become engaged partners in their care and form strong therapeutic alliances with their physicians. As accountable care, value-based purchasing, and other new models of care delivery and financing intensify our focus on patient-centered care and longitudinal relationships with physicians, it is necessary to improve the healthcare system’s capacity to match patients with physicians who fit their specific needs, preferences, and values.

In this perspective, we draw on the insights from research into patient preferences to propose a framework for understanding and organizing the information necessary to successfully match patients and physicians. Specifically, we outline 5 factors that should be considered when matching patients with physicians, and provide examples of the information and attributes that are important to consider within each factor.

1. Communication and decision making. Communication and decision making anchor the patient-physician relationship, and patient preferences in these areas vary considerably. Physician communication style and the tone of patient interactions, inclusiveness of the patient in decision making, and attitudes and approaches to uses of clinical evidence are all important variables to consider when selecting a physician. Clinical measures of individual physician performance or survey data from other patients can be important supports to patient choices in this area.

2. Therapeutic approach. For many elective, “preference-sensitive” conditions, the aggressiveness and intensity of treatment vary among physicians.2 These are precisely the procedures for which patients spend the most time trying to identify the right physician, and it is important that patients understand with clarity the therapeutic options favored by their physician of choice. Similarly, a physician’s willingness to provide complementary or alternative therapies, and his or her use of new technologies or investigational drugs and procedures, are important factors of consideration in this area.

3. Social and cultural appropriateness. Patients should be matched with physicians who can deliver care that is consistent with their social, cultural, or religious preferences. For example, patients from historically disadvantaged or marginalized groups are often more comfortable working with physicians with a special aptitude for or interest in working with those groups.3 Other factors many patients will find important to consider are nationality, ethnicity, or fluency in their preferred language.

4. Cost and value. Economic considerations have a profound effect on healthcare-seeking and -utilization activities.4 As out- of-pocket deductibles rise and patients increasingly bear the costs of care, appropriate financial data, such as expected or estimated out-of-pocket costs, will be key variables to consider in choosing a physician.

5. Practice environment. The attributes of the system within which a physician practices have a profound impact on a patient’s experience with his or her physician. Patients are sensitive to system characteristics such as wait times, the use of patient portals, physician use of electronic health records (EHRs), and the care delivery model in which the physician operates (eg, medical home). Many patients—especially patients with complex illnesses—are especially cognizant of the extent to which clinical interactions across an extended delivery system are coordinated.

Table 1

This framework is intentionally comprehensive and, in many cases, attributes of clinicians and patients will have relevance across the 5 categories. Patient preference will govern the relative importance of each dimension and its attributes; aligning a patient with the right physician requires information across all of these dimensions. outlines preferences of 3 sample patients to demonstrate the profound heterogeneity that must be considered and managed if patients are to be able to select physicians aligned with their unique needs, preferences, and values. True patient-centeredness will only emerge when we acknowledge this reality and build the tools, systems, and strategies to understand and manage this heterogeneity.

Fortunately, there has been a dramatic influx in the availability of the data needed to populate the various components of this framework. Patient groups and societies sometimes offer direction on choice of provider and therapy. Commercial and government websites such as Physician Compare offer information on patient experience and attributes such as communication style and cultural appropriateness. Commercial insurers are releasing tools that allow patients to receive tailored, real-time estimates of out-of-pocket expenses for different providers. Multi-stakeholder organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society have information on system-level factors such as EHR adoption and disease management capabilities. Importantly, certifications from groups like the Joint Commission and data made public by private payers and Medicare can yield information on condition-specific outcomes.

With growing quality, the infrastructure and information exist to move toward a more patient-centered approach to physician selection. But the information is siloed, housed in myriad sources that are hard for patients to navigate and even harder for them to integrate. Helping patients find the right physician requires integrating existing data sources and providing patients with the information they need to select the right physician for their needs. The responsibility for making available these integrated resources will fall on accountable care organizations, physician groups, employers, governments, and patient groups, all of whom share an interest in enabling patients to make sound decisions and begin their healthcare experience by identifying the best physician for their needs.Author Affiliations: Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA (BWP, SHJ); Boston-VA Medical Center, Boston, MA (SHJ); Merck and Co, Inc, Boston, MA (SHJ).

Author Disclosures: The authors report no relationship or financial interest with any entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article. This paper solely reflects the views of the authors and not the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Address correspondence to: Sachin H. Jain, MD, MBA, 33 Avenue Louis Pasteur, 2nd Fl, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: shjain@post .harvard.edu.1. Huckman RS, Kelley M. Public reporting, consumerism, and patient empower- ment. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1875-1877.

2. Institute of Medicine. Patients Charting the Course: Citizen Engagement in the Learning Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

3. Chen FM, Fryer GE Jr, Phillips RL Jr, Wilson E, Pathman DE. Patients’ beliefs about racism, preferences for physician race, and satisfaction with care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):138-143.

4. Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Duan N, Keeler EB, Leibowitz A, Marquis MS. Health insurance and the demand for medical care: evidence from a randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev. 1987;77(3):251-277.

Quality of Life: The Pending Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

February 6th 2026Because evidence gaps in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research hinder demonstration of antifibrotic therapies’ impact on patient quality of life (QOL), integrating validated health-related QOL measures into trials is urgently needed.

Read More

Blister Packs May Help Solve Medication Adherence Challenges and Lower Health Care Costs

June 10th 2025Julia Lucaci, PharmD, MS, of Becton, Dickinson and Company, discusses the benefits of blister packaging for chronic medications, advocating for payer incentives to boost medication adherence and improve health outcomes.

Listen