- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

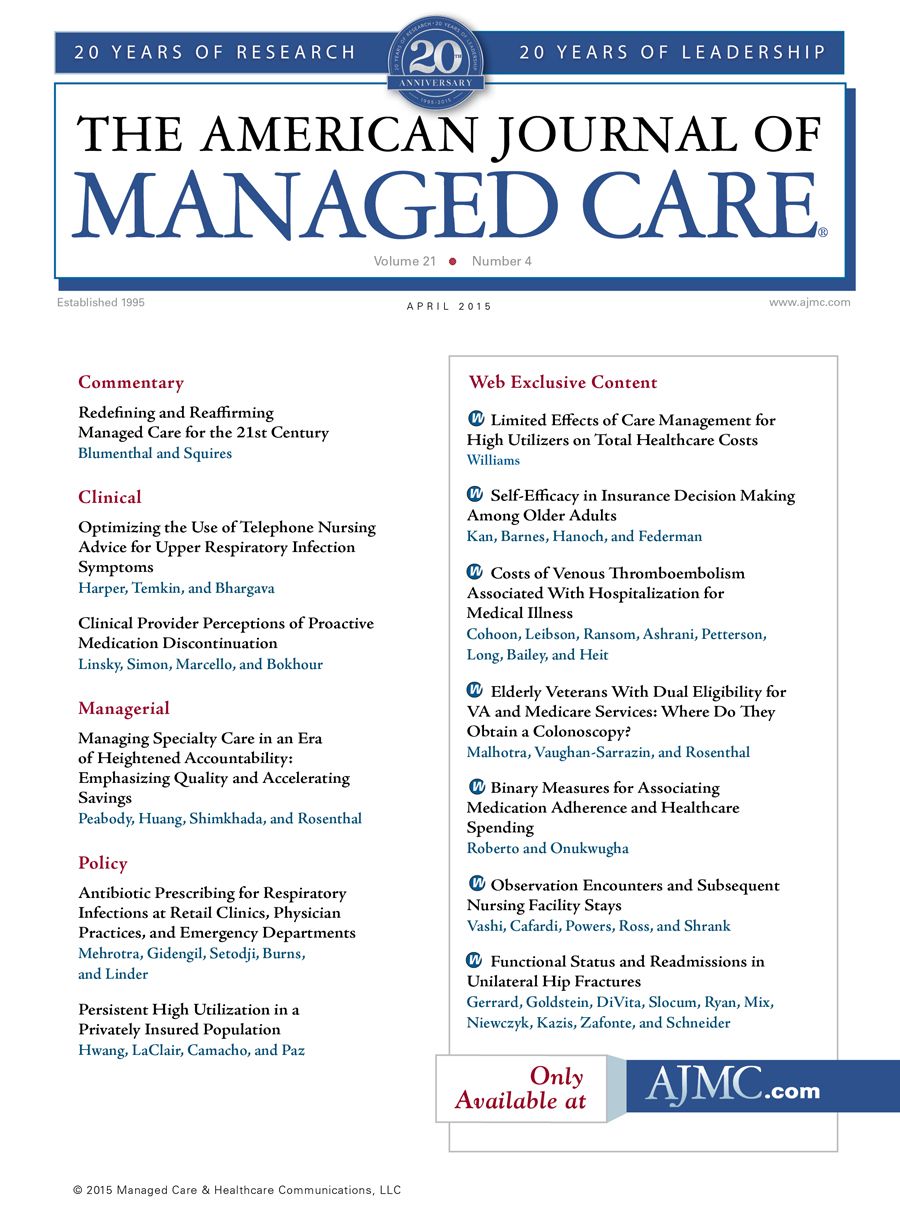

Elderly Veterans With Dual Eligibility for VA and Medicare Services: Where Do They Obtain a Colonoscopy?

This study examines factors impacting the receipt of an outpatient colonoscopy by VA or non-VA providers in older veterans dually eligible for VA/Medicare benefits.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: To examine the receipt of colonoscopy through the Veterans Health Administration (VA) or through Medicare by older veterans who are dually enrolled.

Study Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Methods: The VA Outpatient Care Files and Medicare Enrollment Files were used to identify 1,060,523 patients 65 years and older in 15 of the 22 Veterans Integrated Service Networks nationally, who had 2 or more VA primary care visits in 2009 and who were simultaneously enrolled in Medicare. VA and Medicare files were used to identify the receipt of an outpatient colonoscopy. Patients were categorized as receiving care in community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) (n = 601,337; 57%) or VA medical centers (n = 459,186; 43%) based on where most patient-centered encounters occurred. Analyses used multinomial logistic regression to identify patient characteristics related to the odds of receiving a colonoscopy at the VA or through Medicare.

Results: Patients had a mean age of 76.9 (SD = 7.0) years; 98% were male, 89% were white, and 21% resided in a rural location. Overall, 100,060 (9.4%) patients underwent outpatient colonoscopy either through the VA (n = 33,600; 35.5%) or Medicare providers (n = 65,716; 65.5%). The adjusted odds of receiving a colonoscopy from Medicare providers were higher (P <.001) for patients who were male, white, receiving primary care at CBOCs, and for residents of an urban location. The receipt of colonoscopy through the VA decreased dramatically by age; for example, the odds of colonoscopy by the VA in patients aged >85 years and 80 to 84 years, relative to patients aged 65 to 69 years, were 0.26 and 0.13, respectively. In contrast, the receipt of colonoscopy through Medicare did not decline as markedly with age.

Conclusions: In a national analysis of the receipt of an outpatient colonoscopy by older veterans, more veterans received their colonoscopies through CMS than through the VA. The use of colonoscopy within the VA was found to be more concordant with age-related practice guidelines.

Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e264-e270

The principal finding is that more dually eligible patients had a colonoscopy performed by Medicare providers.

- Patients receiving primary care in main Veterans Health Administration (VA) facilities, members of minority groups, and rural residents were significantly more likely to use the VA to obtain an outpatient colonoscopy.

- The use of colonoscopy through the VA decreased with age—as expected per guidelines—although such decreases by age were less evident through Medicare, thus providing indirect evidence that the use of colonoscopy within the VA may be more consistent with current practice guidelines than the use of colonoscopy by non-VA providers.

The Veterans Health Administration (VA) is the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States. In addition to having VA healthcare eligibility, a significant proportion of veterans are also eligible for healthcare benefits through private insurers, Medicare, Medicaid, or other government programs.1 While such dual eligibility may disrupt continuity of care, it also provides veterans with increased choices, flexibility, and access to care.2,3 The greater access may be particularly germane for certain types of specialty care, which may only be available in larger VA medical centers, and not through most VA community-based clinics.

The failure to account for out-of-system healthcare utilization by veterans poses challenges to effective care coordination. Out-of-system utilization may also lead to inaccurate assessments of the overall quality of care received by veterans, and to inaccurate estimates of the cost and efficiency of the VA and Medicare in general. Therefore, it is important to understand the overall utilization of services by veterans and their patterns of use of VA and non-VA services.

Although prior studies have assessed factors impacting the use of VA and non-VA inpatient and outpatient services by veterans,4-6 little research has examined how veterans use these 2 types of care to obtain outpatient procedures such as colonoscopy.7 Thus, the current study examines how older veterans who are dually eligible for VA and Medicare benefits use VA and non-VA providers to obtain an outpatient colonoscopy. In addition to determining where veterans obtain a colonoscopy, the study sought to identify factors related to the use of VA and non-VA care, and to determine the degree to which the use of colonoscopy by VA and non-VA providers varies according to important clinical factors such as age.

METHODS

Data Sources

Study data were derived from 4 administrative data sources. The VA Outpatient Care File (OPC) contains administrative records for all encounters in VA clinics. Data elements include demographic information, including residential zip code; clinic identifier; clinic specialty (eg, primary care, mental health); principal and secondary diagnoses codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM); and up to 20 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. The VA’s fee-basis program (2009) contains data on encounters provided outside the VA health system that are paid for by the VA. The VA OPC and fee-basis files were used to identify the study cohort and services received through VA benefits.

Information on Medicare enrollment and services received through Medicare was obtained from the VA-CMS Medicare merged data files available through the VA Information Resource Center.8 The VA-CMS merged data files contain the Medicare claims of veterans who were simultaneously enrolled in VA and CMS.8 Medicare data were obtained for fiscal year (FY) 2009 for all VA patients in 15 of the 22 Veterans Integrated Service Networks nationally. For this study, information about enrollment in Medicare was derived from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, while the Carrier Standard Analytic File (ie, Part B) contains claims for physician services provided outside the VA that were reimbursed by Medicare. To create an FY database, Medicare records were merged with the national OPC file and the VA fee-basis care file using a scrambled social security number that is unique across these 3 primary data sources.

Study Patients

The eligible population was drawn from 1,466,340 VA patients 65 years and older (as of October 1, 2009) in the 15 VISNs who had 2 or more visits to a VA primary care provider during FY 2009 (October 1, 2008, to September 30, 2009). Patients were excluded if they were not enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B at the start of the year or if they were enrolled in a Medicare health maintenance organization at any time during the year. The application of these criteria yielded a final study sample of 1,060,523 patients.

Study Variables

The dependent variable was receipt of an outpatient colonoscopy procedure that was performed or reimbursed by the VA or that was reimbursed through Medicare in FY 2010. Colonoscopies were identified by CPT codes. Additionally, colonoscopies that were not performed for diagnostic purposes (ie, screening colonoscopies) were identified based on a previously published algorithm.9

The independent variables of interest included the type of clinic where patients received primary care (ie, a VA medical center [VAMC] or community-based outpatient clinic [CBOC]), age, gender, distance between the veteran’s residence and the nearest VAMC (based on zip code centroids), residential location (urban vs rural), and comorbid illnesses (as defined by widely used ICD-9-CM diagnosis algorithms).10 For patients with primary care visits at both a VAMC and a CBOC, categorization as VAMC or CBOC was based on the site where the majority of primary care encounters occurred; patients with equivalent numbers of visits (n = 14,914) were categorized as VAMC patients. We used residential zip code and census data to initially classify the location into isolated rural, rural, small city, or large city, based on the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes. RUCA codes are measures of rurality that incorporate population density as well as commuting patterns11; these codes were originally developed as a census tract—based classification scheme that combines US Census Bureau Urbanized Area definitions with commuter information to characterize census tracts.12 Our study used a zip code—level approximation to census tract RUCA codes.13 The RUCA algorithm creates 30 mutually exclusive categories representing population density and proximity to nearby urban centers. We categorized the 30 codes into 4 previously defined categories: urban areas, large towns, small rural towns, and isolated small rural towns. The 2 rural categories were then grouped as “rural.”

Analysis

The analysis consisted of 2 steps. First, the characteristics of patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy through the VA and through Medicare were compared using the χ2 or Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Second, a single multinomial logit model was used to identify patient characteristics related to the odds of receiving a colonoscopy through the VA or Medicare relative to receiving no colonoscopy. The model simultaneously controlled for patient age, gender, race, residential location, comorbid conditions, and type of primary care clinic. For each variable or characteristic, the model provided the simultaneous odds of receiving a colonoscopy either through the VA or Medicare, relative to patients without the characteristic. A separate analysis was conducted that only considered screening colonoscopies and found similar results (not presented).

All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board and the Research and Development Committee at Iowa City VA Medical Center.

RESULTS

Study participants had a mean age of 76.9 (SD = 7.0) years; 98% (n = 1,038,849) were male and 20.8% (n = 220,861) resided in a rural location. Eighty-nine percent (n = 946,923) of the sample were white, 7% (n = 74,441) were black, and 2.5% (n = 27,036) were Hispanic; information on race was missing in less than 0.1% (n = 473) of the sample. Fifty-seven percent (n = 601,337) of patients were classified as receiving primary care at a CBOC, and 43.3% (n = 459,186) at a VAMC.

Overall, 100,060 (9.4%) patients underwent an outpatient colonoscopy, and of these, 65,716 (65.5%) received a colonoscopy from Medicare providers; 33,600 (35.5%) from VA providers; and 744 (0.1%) from both the VA and Medicare. These latter patients were excluded from subsequent analyses. Nearly three-fourths of procedures (n = 73,747; 73.7%) were screening examinations. Of the screening procedures, 46,167 (62.7%) were performed by CMS providers, and 27,580 (37.3%) by VA providers.

Table 1

Compared with patients who obtained an outpatient colonoscopy through CMS, patients who obtained a colonoscopy through the VA were younger (P <.001) and were more likely (P <.001) to receive primary care through a VAMC, as well as more likely to live closer to a VAMC and to have comorbid conditions (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, cerebral vascular disease, and chronic renal disease) ().

Table 2

In a multinomial logit model adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidity, a number of factors were independently related to receiving a colonoscopy either through providers from the VA or through Medicare (). Patients receiving primary care at a CBOC, relative to patients receiving primary care at a VAMC, were more likely to undergo a colonoscopy through Medicare, as were patients residing in a large town or urban area. Minority patients were more likely to receive a colonoscopy through the VA, and less likely to receive one through Medicare. Women were less likely than men to have the procedure performed by both the VA and Medicare. Interestingly, the odds of receiving a colonoscopy through the VA decreased dramatically by age (Table 2); for example, the odds of colonoscopy being performed by the VA in patients 85 years or older and aged 80 to 84 years, relative to patients aged 65 to 69 years, were 0.24 and 0.11, respectively. In contrast, these odds were 1.07 and 0.63, respectively, for receiving a colonoscopy from CMS providers, indicating that age was much less of a factor in the provision of colonoscopy through Medicare.

DISCUSSION

The current study examines the patterns of cross-system utilization of VA and Medicare services for outpatient colonoscopy among a cohort of Medicare-eligible veterans who used VA primary care services. Several findings deserve emphasis. First, there were more veterans who received their colonoscopies from Medicare providers than from the VA. Second, the relative likelihood of receiving a colonoscopy from Medicare providers was higher for veterans receiving primary care at a CBOC, relative to veterans receiving primary care at a VAMC, and for veterans residing in an urban location. In contrast, racial minorities and females had higher relative odds of receiving a colonoscopy through the VA. Finally, the receipt of colonoscopy through the VA decreased dramatically with increasing age, but such a decline was less pronounced when the colonoscopy was obtained from Medicare providers.

It is important to consider our findings within the context of other related research. For example, nearly two-thirds of the outpatient colonoscopies were performed by Medicare providers in our study. Prior studies have documented temporal increases in utilization of colonoscopy as a screening modality in the Medicare population.14 However, several studies in VA populations found that although there has been an increase in the use of colonoscopy, fecal occult blood testing remains the predominant mode of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in the VA,11 in contrast to the findings of studies in Medicare populations. These differences may reflect greater access to and availability of colonoscopy in private sector settings, as well as differences in financial incentives.

A prior study assessing demographic variations in CRC screening in a Washington state Medicare population showed that urban residents were 10% more likely to obtain a screening colonoscopy than rural residents.15 Our data also show that urban veterans were 20% more likely than rural veterans to obtain an outpatient colonoscopy from Medicare providers. In contrast, urban residents were 15% less likely than rural residents to obtain a colonoscopy from the VA—possibly due to the higher density of gastroenterology services in urban locations. It has been found that the reliance on the VA for outpatient care was lower for dually eligible veterans from counties with a higher number of hospital beds, where choices for healthcare tend to be greater.6

Our study also found that patients receiving primary care at CBOCs had markedly lower odds (0.54) of having a colonoscopy performed by VA providers compared with veterans receiving primary care at a VAMC. In contrast, patients at CBOCs had higher odds (1.23) of getting a colonoscopy from a Medicare provider. These findings are consistent with our prior work showing that CBOC patients are less likely to have procedures for CRC screening provided through the VA,16 as well as other studies showing that CBOC patients are more likely to use non-VA services.17,18 For instance, Liu and colleagues reported that Medicare-eligible veterans receiving primary care in CBOCs had 22% fewer VA specialty care visits and 21% more Medicare-reimbursed specialty care visits than patients receiving primary care at VAMCs.17

We also found that black and Hispanic patients were more likely than white patients to obtain a colonoscopy through the VA, and were less likely to obtain one through Medicare. These findings are also consistent with studies showing that minority patients are more likely to be reliant on VA outpatient care services. In a study by Hynes and colleagues,6 black veterans were increasingly likely to rely on VA care—they were more likely to rely on VA care exclusively than were nonblacks (OR, 2.32)—as well as to rely on some form of VA care than to use Medicare exclusively.6 Previous survey research also showed that blacks, compared with nonblacks, are more likely to prefer VA to non-VA providers for their outpatient care.18 A substantial amount of research documents racial/ethnic disparities in access to healthcare in non-VA settings, with minorities likely to face greater access barriers.19,20 Since VA care is available without payment of an annual insurance premium, nonfinancial access barriers may help to explain our findings. This raises concerns that policy initiatives aimed at restructuring VA services may disproportionately affect minority veterans. Our further finding that women were less likely to receive colonoscopy through both the VA and Medicare is also consistent with prior analyses of Medicare data showing gender-related disparities in the use of colonoscopy.21

Lastly, our data provide indirect evidence that the use of colonoscopy within the VA is more concordant with age-related practice guidelines. For instance, the odds of obtaining a colonoscopy within the VA decreased markedly with increasing age. For example: the adjusted odds of receiving colonoscopy in patients 85 years or older and aged 80 to 84 years, relative to patients aged 65 to 69 years, were 0.24 and 0.11, respectively. In contrast, these odds were 1.07 and 0.63, respectively, for patients receiving colonoscopy by CMS providers. Patient requests and preferences for colonoscopy may play a role in utilization patterns. However, current age-related guidelines for the use of colonoscopy do not explicitly consider patient requests for a procedure independent of physician judgment.

A number of other factors may drive age-related utilization patterns among patients receiving colonoscopy through Medicare, including financial incentives that do not exist within the VA. The US Preventive Services Task Force advises against routine screening in those aged 75 to 85 years and against any screening of those 85 years or older.22 Prior work from Goodwin and colleagues assessing overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population, showed that among patients aged 75 to 79 years and 80 years or older at the time of initial negative screening colonoscopy, 46% and 33%, respectively, received a repeated examination within 7 years.23 The higher rate of colonoscopy in the elderly patients is of special concern, given increased potential for complications and decreased benefit.24,25

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge several potential limitations of our study. Importantly, while our study relied on administrative data, prior studies have shown that administrative data may not reliably capture major procedures.26,27 In addition, information on comorbid conditions was captured from ICD-9-CM codes, which may lack sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, administrative data may not adequately assess severity of illness or categorize patients according to their risk for colon cancer28 and do not capture important domains, such as functional status, that may impact the use of colonoscopy. We assessed the use of outpatient colonoscopy and then stratified the data into screening and diagnostic colonoscopies using a previously established algorithm. The sensitivity and specificity of this algorithm may be limited.11,28 Nevertheless, our results were almost identical. The study used a cross-sectional design and did not account for colonoscopies that patients may have received prior to 2009; thus, eligibility for CRC screening was not directly examined. Similarly, we were unable to assess other factors related to the clinical appropriateness of any of the procedures. We did not have access to the data more recent than this at the time the study was conducted. Therefore, given recent changes in VA resources over the past 5 years for colonoscopy, utilization patterns for non-VA colonoscopy may have changed. Finally, we only studied veterans who were 65 years and older, so these results may not be applicable to younger veterans.

CONCLUSIONS

In a national analysis of the receipt of an outpatient colonoscopy by elderly veterans who are dually enrolled in both the VA and Medicare, more veterans obtained their colonoscopies through CMS than through the VA. Patients receiving primary care through a CBOC and residing in an urban setting were more likely to receive a colonoscopy through CMS. In contrast, females and minority patients were more likely to use the VA for obtaining their outpatient colonoscopy. Lastly, the use of colonoscopy through the VA decreased with age, as expected per guidelines, although such decreases by age were less evident through Medicare, providing indirect evidence that the use of colonoscopy within the VA may be more consistent with current practice guidelines than the use of colonoscopy by non-VA providers.

Author Affiliations: Center for Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation, Iowa City VA Medical Center (AM, MV-S, GER), IA; Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine (AM, MVS, GER), Iowa City, IA; Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Iowa (GER), Iowa City, IA.

Source of Funding: Center of Innovation Award (CIN 13-412) from the Health Services Research and Development Service, Veterans Health

Administration; and a Clinical and Translational Science Award (2 UL1TR000442-06) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science.

Dr Malhotra was supported by a Quality Scholars Fellowship from the Office of Academic Affiliations, Veterans Health Administration.

Author Disclosures: Drs Malhotra, Vaughan-Sarrazin, and Rosenthal are Veterans Health Administration (VA) employees. Dr Rosenthal has received numerous VA grants and has attended VA-sponsored meetings. Dr Vaughan-Sarrazin reports no relationship or financial interest withany entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article.

Authorship Information: Concept and design (AM, MV-S, GER); acquisition of data (MV-S, GER); analysis and interpretation of data (AM, MV-S, GER); drafting of the manuscript (AM, MV-S); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (AM, GER); statistical analysis (AM, MV-S); and supervision (MV-S, GER).

Address correspondence to: Ashish Malhotra, MD, CADRE, Bldg 42, Iowa City VA Medical Center, 601 US Highway 6, Iowa City, IA 52246. E-mail: ashish.malhotra@va.gov.

REFERENCES

1. Shen Y, Hendricks A, Zhang S, Kazis LE. VHA enrollees’ health care coverage and use of care. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(2):253-267.

2. Wolinsky FD, An H, Liu L, Miller TR, Rosenthal GE. Exploring the association of dual use of the VHA and Medicare with mortality: separating the contributions of inpatient and outpatient services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:70.

3. Wolinsky FD, Miller TR, An H, Brezinski PR, Vaughn TE, Rosenthal GE. Dual use of Medicare and the Veterans Health Administration: are there adverse health outcomes? BMS Health Serv Res. 2006;6:131.

4. Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, Hasche J, Reis B, Pietz K. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs health care among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):762-791.

5. Wright SM, Daley J, Fisher ES, Thibault GE. Where do elderly veterans obtain care for acute myocardial infarction: Department of Veterans Affairs or Medicare? Health Serv Res. 1997;31(6):739-754.

6. Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K, et al. Veterans’ access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care. 2007;45(3):214-223.

7. French DD, Margo CE, Campbell RR. Comparison of complication rates in veterans receiving cataract surgery through the Veterans Health Administration and Medicare. Med Care. 2012;50(7):620-626.

8. Hynes DM, Cowper D, Manheim L, et al. Research findings from the VA-Medicare Data Merge Initiative: Veterans’ enrollment, access anduse of Medicare and VA health services (XVA 69-001). report to the Undersecretary of Health Department of Veterans Affairs. Hines, IL: VA Information Resource Center, Health Services Research and Development Service; 2003.

9. El-Serag HB, Petersen L, Hampel H, Richardson P, Cooper G. The use of screening colonoscopy for patients cared for by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2202-2208.

10. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

11. RUCA [Rural Urban Commuting Area Codes] 2.0. University of Washington WWAMI Rural Health Research Center website. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-data.php. Accessed April 15, 2015.

12. Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149-1155.

13. Larson EH. RUCA Version 1.11: RUCA ZIP Code Approximation Methodology. University of Washington WWAMI Rural Health Research Center website. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca1/rucamethodology11.php. Accessed April, 15, 2015.

14. Fenton JJ, Cai Y, Green P, Beckett LA, Franks P, Baldwin LM. Trends in colorectal cancer testing among Medicare subpopulations. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(3):194-202

15. Ko CW, Kreuter W, Baldwin LM. Persistent demographic differences in colorectal cancer screening utilization despite Medicare reimbursement. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:10.

16. Malhotra A, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Charlton ME, Rosenthal G. Comparison of colorectal cancer screening in veterans based on the location of primary care clinic. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014;5(1):24-29.

17. Liu CF, Chapko M, Bryson CL, et al. Use of outpatient care in Veterans Health Administration and Medicare among veterans receiving primary care in community-based and hospital outpatient clinics. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5, pt 1):1268-1286.

18. Washington DL, Harada ND, Villa VM, et al. Racial variations in Department of Veterans Affairs ambulatory care use and unmet health care needs. Mil Med. 2002;167(3):235-241.

19. Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;(57, suppl 1):108-145.

20. Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW. Racial and ethnic differences in access to and use of health care services, 1977 to 1996. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;(57, suppl 1):36-54.

21. Gancayco J, Soulos PR, Khiani V, et al. Age-based and sex-based disparities in screening colonoscopy use among Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(7):630-636.

22. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627-637.

23. Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo YF. Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1335-1343.

24. Arora G, Mannalithara A, Singh G, Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G. Risk of perforation from a colonoscopy in adults: a large population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3, pt 2):654-664.

25. Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(12):849-857.

26. Katz JN, Barrett J, Liang MH, et al. Sensitivity and positive predictive value of Medicare Part B physician claims for rheumatologic diagnoses and procedures. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1594-1600.

27. Du X, Freeman JL, Warren JL, Nattinger AB, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Accuracy and completeness of Medicare claims data for surgical treatment of breast cancer. Med Care. 2000;38(7):719-727.

28. Ko CW, Dominitz JA, Neradilek M, et al. Determination of colonoscopy indication from administrative claims data. Med Care. 2014;52(4):e21-e29.

Building Trust: Public Priorities for Health Care AI Labeling

January 27th 2026A Michigan-based deliberative study found strong public support for patient-informed artificial intelligence (AI) labeling in health care, emphasizing transparency, privacy, equity, and safety to build trust.

Read More

Ambient AI Tool Adoption in US Hospitals and Associated Factors

January 27th 2026Nearly two-thirds of hospitals using Epic have adopted ambient artificial intelligence (AI), with higher uptake among larger, not-for-profit hospitals and those with higher workload and stronger financial performance.

Read More

Motivating and Enabling Factors Supporting Targeted Improvements to Hospital-SNF Transitions

January 26th 2026Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) with a high volume of referred patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias may work harder to manage care transitions with less availability of resources that enable high-quality handoffs.

Read More