- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

When to Stop Colorectal Cancer Screening?

How does age, sex, comorbidity, and screening history influence the cost-effectiveness of continuing colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in older adults?

The optimal stopping ages for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening based on sex, comorbidity, and screening history offers critical insights for patients and clinicians, according to new research.1 Specifically, health status and past screenings significantly influence the benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of continued CRC screening.

The economic evaluation analysis is published in JAMA Network Open.

“As expected, the results suggest older optimal stopping ages for cohorts with lower comorbidity statuses because they have a longer life expectancy,” wrote the researchers of the study. “In contrast, prior screening with negative results was associated with lower CRC risk and less favorable cost-effectiveness of additional screening. Despite a lower CRC risk for females than males, the results showed that CRC screening at older ages is more cost-effective in females than males.”

In May 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended for the first time that patients aged 45 to 49 years be screened for CRC, which had an immediate effect on testing rates in this age group.2 The findings also showed that screening in this age group can be affected by socioeconomic status and locality. But when is he optimal time to stop screening?

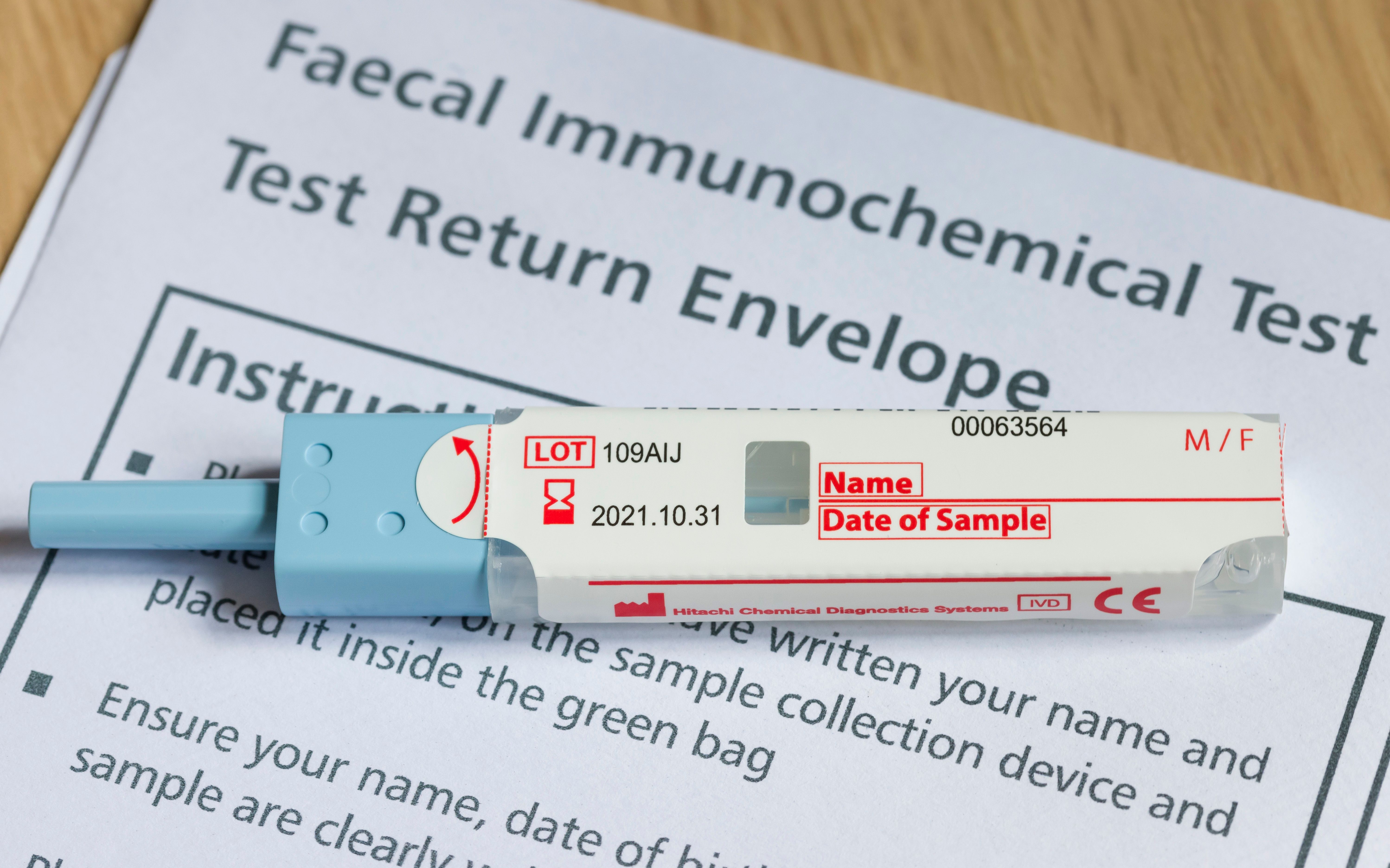

The researchers validated the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon (MISCAN-Colon) model against community-based data from 3 integrated US health care systems.1 The study simulated the benefits, harms, and costs of CRC screening from ages 76 to 90 years, stratified by sex, comorbidity status, and prior screening history. Screening scenarios included fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), colonoscopy, or combinations of both, with outcomes measured in incremental costs and quality-adjusted life-years gained (QALYG).

Costs were calculated from a societal perspective, and utilities were discounted at 3% annually. Optimal stopping ages for screening were determined as the oldest age at which additional FIT or colonoscopy remained cost-effective under a $100,000 per QALYG threshold. Additionally, sensitivity analyses explored variations in postpolypectomy surveillance and complication rates by comorbidity.

The first subcohort included 25,974 adults, predominantly aged 76 to 80 years (54.7%), with a negative colonoscopy result 10 years prior. The second subcohort encompassed 118,269 adults, with 90.5% aged 76 to 80 years, who had a negative FIT result 1 year prior.

Reduced incremental benefits and cost-effectiveness of additional screenings were observed with older age, male sex, higher comorbidity levels, and recent CRC screenings. For females aged 76 years without comorbidities and a negative colonoscopy result 10 years prior, 1 additional colonoscopy cost $38,226 per QALYG, whereas costs surged to $1,689,945 per QALYG for females aged 90 years with similar characteristics. Optimal stopping ages varied by cohort characteristics, ranging from younger than 76 to 86 years for colonoscopy and younger than 76 to 88 years for FIT, underscoring the need for personalized screening strategies.

However, the researchers noted several limitations. First, model validation against CRC data revealed higher estimated incidence and mortality rates compared to observed rates in younger cohorts with a negative FIT result 1 year prior, potentially overestimating cost-effectiveness for FIT-only screening histories. Second, the assumption of 100% adherence to follow-up tests after positive results or detected polyps may not have reflected real-world behavior, though scenarios of suboptimal adherence were indirectly evaluated, providing insights into outcomes with lower screening uptake.

Despite these limitations, the researchers believe these findings can help guide development and patient-centered decision-making for when to stop CRC screening in older adults.

“Findings from this economic evaluation using community-based data on CRC risk suggest that the clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and optimal stopping age for CRC screening are associated with sex, comorbidity, prior screening, and future screening modality,” wrote the researchers. “Therefore, personalizing CRC screening based on these factors after age 75 years may play a role in the improvement of screening efficiency and reduction of potential harms.”

References

1. Harlass M, Dalmat RR, Chubak J, et al. Optimal stopping ages for colorectal cancer screening. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(12):e2451715. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.51715

2. Bonavitacola J. CRC screening increases in patients aged 45 to 49 after USPSTF recommendation. AJMC. October 7, 2024. Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.ajmc.com/view/crc-screening-increases-in-patients-aged-45-to-49-after-uspstf-recommendation.