- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Top 5 Causes of Death on the First Labor Day Fueled by Harsh Working Life

Infectious diseases were the leading causes of death on the first Labor Day, just ahead of a major epidemiological shift that brought both vaccines to fight these deadly ailments but also the rise of cigarette smoking.

These days, when one looks at CDC’s list of the top 5 causes of death in the United States, they include 4 longtime causes—heart disease, cancer, accidents, and stroke—and one unheard of before 2020, COVID-19. Despite the upheaval of the pandemic, the causes that make up 3 of the top 5 and 8 of the top 10 causes have been relatively constant in recent years: They are degenerative diseases, meaning their effects build up over time. COVID-19, an infectious disease, is an anomaly.

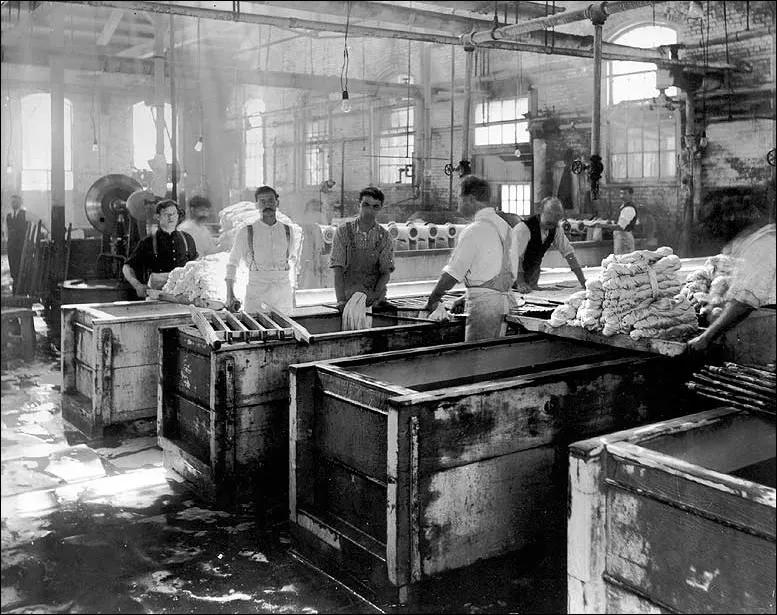

Workers in a silk plant in Paterson, New Jersey, at the turn of the 20th century. | Image: National Park Service.

But when Americans first celebrated Labor Day, the opposite was true. Working conditions in US cities had become so dangerous and unhealthy that it was not hard for labor leaders to convince big city mayors to celebrate workers with parades, starting in 1882 in New York City. Factories of the Gilded Age were crowded, dirty, and dangerous; wounds might not be properly cleaned and could become infected, and with no days off, men, women, and even children came to factories with illnesses that would spread through the plant.

America's epidemiological shift from a population more likely to die from infectious disease to one more affected by chronic conditions has its roots with the labor movement of the 1880s and 1890s, when awareness of low wages and factory conditions, and their effects on health, picked up steam. After that first New York City parade, 4 states created Labor Day celebrations by 1887. When the Pullman workers’ strike disrupted rail traffic in the summer of 1894, President Grover Cleveland sought labor peace by making the first Monday in September a holiday that year.

According to “The Rise of the Current Mortality Pattern of the United States, 1890–1930,” by Hiroshi Maeda, during the final decade of the 19th century, “the higher infectious disease and overall death rates were—a direct relationship.”1 Infectious disease spread not only due to lack of vaccines but also due to lack of cleanliness, which also contributed to high rates of deaths associated with pregnancy and childbirth; according to US Census data on file at CDC, among 11,257 pregnancy-related deaths that occurred in 1890 (on 875,521 deaths overall), 5295 occurred in childbirth.2

What kinds of disease flourished in US cities? Infectious diseases accounted for 3 of the top 5 causes of death in the United States based in the 1890 census, which was published in 1894 during the year of the first Labor Day:

- Consumption (now called pulmonary tuberculosis), 11.8% of deaths

- Pneumonia, 7.8%

- Diarrhea, 5.3%

- “Diseases of the heart,” 5.1%

- Stillbirths, 3.8%

Other infectious diseases rounded out the top 10 causes of death in 1890, including diphtheria (3.2%); cholera infantum or “summer diarrhea” (3.14%), which was seen in children and caused by swallowing dirty water; typhoid fever (3.09%); and bronchitis (2.4%).

What caused the shift away from infectious disease as the leading cause of death? World War I played a key role, for 2 reasons.

First, the pandemic of 1918-1919, known as the “Spanish flu,” led to a race to develop vaccines for soldiers fighting in the war. Although the pandemic began to ease before vaccines were ready, and thus results of testing of the vaccines were inconclusive, the experience set in motion the procedures that would lead to the development of waves of vaccines in the first half of the 20th century. By midcentury, the world had vaccines for smallpox, tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, typhus, tetanus, influenza, and polio, although it would take decades for these to be evenly distributed.

The effects on longevity were remarkable: In 1900, US life expectancy was 45 years, with men faring slightly worse because so many died in industrial accidents. By 1950, US life expectancy had climbed to 66.5 years for men and 71.8 for women; this phenomenal rise belied the shift to the new culprit in American deaths, which was cigarette smoking. CDC cites smoking as the leading cause of preventable death, given its links to heart disease, cancer, diabetes, respiratory ailments, and scores of inflammatory conditions.

World War I was the link here, too: Tobacco companies gave free cigarettes to US and Allied troops, and smoking would be carried back home by young men to cities and small towns alike. Women at midcentury smoked far less than men, which was seen in the difference in life expectancy.

By 1930, Madea writes, the “urban penalty” had been completely reversed; Urban dwellers were now less likely to see early mortality from infectious disease than rural residents, a pattern that would continue. Between 1900 and 1930, he found, mortality declined 42% in cities with at least 500,000 people. “Such a striking shift resulted because, generally, the more urban the location was, the larger the reduction in the mortality penalty was during the epidemiologic transition,” he concluded.

References

- Maeda H. The rise of the current mortality pattern of the United States, 1890-1930. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(4):639-646. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx203

- Billings JS. Report on the Vital and Social Statistics of the United States at the Eleventh Census, 1890. US Census Office, Department of the Interior. Government Printing Office; 1894. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsushistorical/vsush_1890_3.pdf

Politics vs Science: The Future of US Public Health

February 4th 2025On this episode of Managed Care Cast, we speak with Perry N. Halkitis, PhD, MS, MPH, dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health, on the public health implications of the US withdrawal from the World Health Organization and the role of public health leaders in advocating for science and health.

Listen

Bird Flu Risks, Myths, and Prevention Strategies: A Conversation With the NFID's Dr Robert Hopkins

January 21st 2025Joining us for this episode of Managed Care Cast is Robert H. Hopkins Jr, MD, medical director at the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID), who will help separate fact from fiction about avian influenza and discuss what needs to be done to prevent a future escalation.

Listen