- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

The Evolving Science of Genetic Carrier Screening

Several professional societies have published guidelines for preconception and prenatal carrier screening.1,2,3 These recommendations are based on ancestry and personal history. This article discusses the limitations of current carrier screening guidelines and the evolving technologies of expanded genetic carrier screening, which can be offered regardless of race or ethnicity.

Limitations of Current Carrier Screening Guidelines

Condition-directed carrier screening focuses on the risk assessment of individual conditions.4 The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) provides recommendations for carrier screening of genetic diseases including cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, hemoglobinopathies (including sickle cell disease, α- and β-thalassemias), fragile X, and Tay-Sachs disease.1 ACOG recommends pan-ethnic carrier screening only for cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy.1 For other genetic conditions, ACOG recommends an approach based on personal or family history, as well as ethnic origin.

There are limitations associated with condition-directed carrier screening, including that it relies on accurate ascertainment of the patient’s family history and ancestry.4 Some of these limitations include:

- Patients may have inaccurate knowledge of ancestry. Among 99 anonymously surveyed participants, approximately 9% did not know their biological parents’ heritage, and 40% did not know the heritage of all 4 grandparents.5 In another study, only 30% of patients of Mediterranean origin correctly self-reported their ancestry without a family history consultation.6 For this reason, patient knowledge of their own ancestry can be a barrier in implementing condition-directed carrier screening which relies on knowledge of one’s ancestry.

- The effects of an increased multiethnic society. Increasing inter-ethnic marriages will eventually result in an increased prevalence of heterozygous states and a wider population.7,8 It is also difficult to categorize a patient’s ethnic origin into a specific group.9 In one study, patients that self-identified as having African ancestry had an average of 12.4% European ancestry and 79.3% African ancestry.6 The variability was even higher in patients who self-reported as having Latin American ancestry. These patients had an average of 12.0% African, 24.4% Native American, and 52.1% European ancestry.6 The unreliability of ethnicity classification can be avoided if screening is offered to all women.9 In fact, ACOG recommended in 2005 that all patients should be offered cystic fibrosis carrier screening because of the “increasing difficulty in assigning a single ethnicity to individuals.”1

- Genetic conditions do not solely exist in specific ethnic groups.4 Although certain ethnic groups have higher rates of heterozygous states of a specific genetic condition and have a higher risk of being affected by the disease, individuals from other ethnic groups may also be carriers, albeit, at a lower frequency.

- At risk individuals left without screening because of condition-based screening that relies on accurate disclosures of family history and carrier status. Disclosure among family members may be incomplete. In a study examining family history and carrier status disclosure patterns of cystic fibrosis, carriers with a family history of cystic fibrosis informed only 84% of their living parents, 56% of their siblings, and even fewer informed their second- and third-degree relatives.10

- Conflicting recommendations and guidelines on condition-based genetic screening from both ACOG and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). The ACMG recommended screening panel differs from the minimum required tests suggested by ACOG for individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.1,3

- Limited patient knowledge. Screening for a restricted number of specific genetic conditions restrains patient knowledge and the amount of genetic information available to the patient.4 Expanded screening would avoid missing cases of rare disorders for which morbidity and mortality may be reduced by early intervention.11

Expanded Carrier Screening

Evolving developments in laboratory technologies have resulted in commercially available expanded carrier screening panels.11 In expanded carrier screening, all patients are screened for a large number of conditions regardless of one’s race or ethnicity.4 Although expanded carrier screening panels typically include all of the genetic conditions recommended by current guidelines, they may include hundreds of other conditions, many of which are rare.4

A joint statement from ACMG, ACOG, the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC), Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recognized that expanded carrier screening, rather than condition-based screening, can be a reasonable approach for patients.4 The ACOG Committee on Genetics also published a separate committee opinion stating that ethnic-specific, pan-ethnic, and expanded carrier screening are all acceptable approaches for preconception and prenatal genetic carrier screening.12

There are diverse offerings in commercially available expanded carrier screening panels with varying panel sizes (Table 1)13-17 and assay technologies.18 Even 2 seemingly identical expanded carrier screening panels with similar technology that test the same number of genes may have different sensitivities. The differences in sensitivities may be caused by the number of interrogated positions in each gene and how detected variants are interpreted.18 The service providers, names of expanded carrier panels, and the mutation components covered are evolving rapidly. Thus, when considering use of expanded carrier screening technology, it is important to consider the finer elements of their make-up and design, particularly given the extent to which screening results can affect the lives of those screened.

Assay Technologies

One approach used to detect mutations in expanded carrier screening panels is a “full-exon sequencing strategy.”18 With this approach, next-generation sequencing (NGS) is used to assess bases across protein-coding regions known as exons, along with other noncoding regions which have acknowledged contributions to disease pathogenesis.18 This sequencing method can probe thousands of bases per gene and can identify all common variants in addition to rare novel variants. Because full-exon sequencing may uncover novel variants, this strategy requires novel-variant curation, a process used to interpret the clinical impact of observed variants.18

Some strategies bypass the need for novel-variant curation by restricting interrogation to a set of known and predefined pathogenic variants, usually only between 1 to 50 variants per gene. This strategy is called “targeted genotyping.”18 Polymerase chain reaction, microarrays, and NGS can be used in targeted genotyping.18 The smaller assayed regions and lack of novel variant interpretation requirements make targeted genotyping relatively inexpensive. However, it has lower detection rates than full-exon sequencing.18 These lower detection rates may eventually lead to an increase in overall healthcare spending because of the cost of care for unknown affected pregnancies.18,19 Given the challenges of achieving both high sensitivity and high specificity in a low-labor process, careful selection of variants is essential.

Framework for Evaluating and Designing Expanded Screening Panels

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established the ACCE framework as a process to evaluate genetic testing.20 ACCE derives its name from the 4 criteria for assessing a genetic test:

- Analytic validity

- Clinical validity

- Clinical utility

- Associated ethical, legal, and social implications

To optimize these 4 criteria, experts have proposed that expanded carrier screening panels should be designed with the following considerations:18

- Candidate diseases being evaluated should be clinically “desirable.” Included diseases should be considered “severe” or “profound.”

- Aggregate panel sensitivity should be maximized. One way to maximize aggregate panel sensitivity is to select high-incidence diseases.

- Per-disease sensitivity and negative predictive value should be maximized. High confidence in test results for both carrier and noncarrier status can be achieved for each genetic condition.

- Specificity should be maximized to near 100% by using carefully designed assay and variant curation methods.

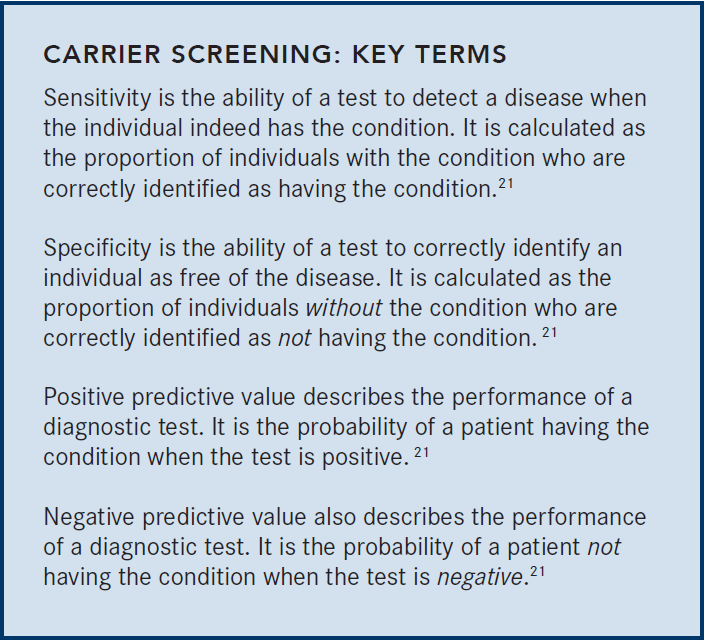

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values are important determinants of analytical and clinical validity.

Analytical Validity

Analytical validity means that a test can predict the presence or absence of a genetic mutant.22

ACMG and the College of American Pathologists have published recommendations on the necessary performance parameters of genetic testing using NGS technology. In particular, these organizations recommend measuring analytical sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of an NGS-based test.23,24 Expanded carrier screening panels with greater than 99.99% analytical sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy and greater than 99.9% inter- and intra-assay reproducibility are commercially available.25

Clinical validity. Clinical validity refers to the ability of a test and to accurately identify couples at risks of passing on serious genetic diseases to their offspring.26 Clinical validity depends on several factors, such as high clinical sensitivity (a positive test when the genetic disorder is present), and specificity (a negative test when the genetic disorder is absent).27 Another factor is an established relationship between genotype and condition phenotype. To establish clinical validity, the genetic testing should be applied in populations where the test may be present.27

Genomic assays demand careful curation processes to determine which genetic variants are clinically important and should be reported to clinicians and patients. The test’s sensitivity and specificity are directly affected through the process of variant interpretation.18 In these interpretive processes, there is a tradeoff among sensitivity, specificity, and labor. For instance, processes that rely only on computational methods in a low-labor workflow typically have low sensitivity and specificity.18

One way to achieve high-throughput variant curation is to use an automated process to collect evidence, like population frequency, computation protein structure information, etc. These pieces of evidence are then manually reviewed, along with functional studies and available clinical information to classify the variant.18 This process can be combined with a rule-based system to classify variants with no literature reports and those with high prevalence in unaffected populations.18 This method of variant curation achieves higher sensitivity and specificity than purely automated processes.18

Panel Constitution

Optimal sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive values, and positive predictive values are requisites for a clinically useful genetic test. Panel constitution is also equally important for a carrier screening panel.18

Several professional societies have published recommendations regarding the selection of conditions to be screened in expanded carrier screening panels.18 Instead of including as many disorders as possible, clear criteria should be established for panel constitution.28 According to ACOG and ACMG, genes being screened should have a well-defined relationship with a phenotype. Moreover, the condition should cause cognitive or physical impairment, have a detrimental effect on the quality of life, require medical or surgical intervention, or have an early onset.4,12 The European Society of Human Genetics also states that “an important screening criterion is that the natural course of the disease screened should be adequately understood, and that an acceptable and reliable test should be available with known sensitivity, specificity and predictive values.”29

Conditions to be included in an expanded carrier screening panel. Disease severity is an important criterion for a condition to be included in carrier screening. A severity classification algorithm was proposed and evaluated in a survey study of 192 healthcare professionals.30 In this algorithm, disease characteristics were classified as tier 1, 2, 3, and 4 (Table 2).30

Using disease characteristics, conditions can be classified as mild, moderate, severe, and profound based on the number of tier characteristics30:

- Profound diseases have more than 1 tier 1 characteristic.

- Severe diseases have at least 1 tier 1 characteristic or several tier 2 or 3 characteristics.

- Moderate diseases are those with at least 1 tier 3 characteristic but no other characteristics from tiers 1 or 2.

- Mild diseases are those without any tier 1, 2, or 3 characteristics.

Experts have proposed that expanded carrier screening should prioritize screening of “severe” and “profound conditions.”18 “Moderate” conditions may also be screened if results can provide an opportunity for early intervention.

Reproductive Decisions After Receipt of Expanded Carrier Screening Results

The utility of an expanded carrier screening panel can be illustrated by the likelihood that at-risk couples alter their reproductive decisions based on the results of the screening.31 Preliminary evidence suggests that couples do make reproductive choices based on expanded carrier screening results. In one study of individuals who underwent preconception or prenatal expanded carrier screening for up to 110 genes, 64 couples received preconception screening and were determined to be at risk.31 70% of these couples were not pregnant when receiving results, and of that percentage, the majority (62%) planned to use in vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic diagnosis or prenatal diagnosis in future pregnancies.31 Only 29% did not plan to change their reproductive decisions after discovering the results.31 Importantly, disease severity was significantly associated with changes in reproductive decisions (P = .0001).31

Other studies also support the utility of expanded carrier screening. Out of 6643 individuals (3738 couples) in a study of infertile couples tested with expanded carrier screening, 1666 (25.1%) screened positive for at least one disorder.32 In 8 couples, both reproductive partners tested positive for the same genetic disorder, which placed them at risk for having an affected offspring.32 Three of these couples were both carriers for cystic fibrosis. Two of these couples carrying the mutation did not complete in vitro fertilization, and another couple became pregnant before her obstetric provider obtained chorionic villus sampling.32 Four couples were at risk for having a child with other recessive genetic conditions, including palmitoyltransferase II deficiency, Gaucher disease, GJB2-related DFNB-1 nonsyndromic hearing loss, and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase deficiency. These couples opted for preimplantation genetic testing to their embryos, and all patients delivered unaffected babies.32

After discovering that they are genetic carriers for a serious condition, most couples altered their reproductive decisions to avoid having an affected child. Taken together, these studies support the use of expanded genetic screening in the preconception and prenatal period.

Comparison of Expanded Screening to Guideline-Based Screening

Expanded carrier screening has been compared to current guideline-based conventional screening. In the largest study to date among reproductive-aged individuals without any known indication for specific genetic testing (N = 346,790), expanded carrier screening increased the detection of carrier status for recessive conditions when compared to conventional screening.33 For example, even though the Ashkenazi Jewish population already represents the broadest ethnicity-specific panel according to ACOG and AMCG guidelines, 55% of fetuses (95% CI, 52%-59%) with severe or profound genetic conditions in this population would have been missed using a guideline-based screening panel.33 Of Middle Eastern couples, 91% of fetuses (95% CI, 87%-94%) would not have been identified by a guideline-based screening panel.33 Ethnicity-based panels were unable to detect many of the severe and profound genetic conditions in other ethnic groups (Table 3).33

The superiority of variant detection by expanded carrier screening panels has been corroborated by other studies. During a study of 506 individuals of Jewish descent, expanded screening identified a larger number of pathogenic genetic variants than traditional screening panels,34 and 27% of positive carriers would have been missed using traditional screening panels.34 In another study evaluating carrier screening in 27 sperm donors, expanded carrier screening panels identified 96 variants likely associated with severe disease variants among 81 genes.35 Just 6% of the variants were distinguished by traditional guideline-recommended panels.35

Conclusions

Condition-directed preconception and prenatal carrier screening focuses on risk assessment of individual conditions based on ancestry, as well as family and personal history.4 There are limitations associated with current guideline-based condition-directed carrier screening. Some of these limitations include the reliance on accurate ascertainment of the patient’s family history4 and the difficulties in implementing guideline-based recommendations in an increasingly multiethnic society.7,8

The emergence of NGS technology allows the possibility of expanded carrier screening. In expanded carrier screening, all individuals are offered screening for a set of conditions regardless of race or ethnicity.4 According to the ACCE framework, expanded carrier screening should have optimal analytic validity, clinical validity, clinical utility, and accepted ethical, legal, and social implications.20 Diseases included should typically be considered “severe” or “profound.” A severity classification algorithm was proposed and evaluated, and can serve as a framework for future expanded carrier screening panel design.30

Expanded carrier screening has been compared with current guideline-based carrier screening among reproductive-aged individuals. In the largest study to date, expanded carrier screening increased the detection rates of carrier status for recessive conditions and detected more severe or profound conditions that would have been missed by guideline-based screening panels.33

Evolving technologies may overcome the limitations of guideline-based carrier screening. With the variety of available panels, it is important to consider the design, what it is testing for, and how useful the results of the panel are for individuals or couples. Expanded carrier screening panels with high analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility are commercially available and have the potential to further enable couples to make reproductive choices according to their values.

- ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 691: carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e41-e55. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001952.

- Langfelder-Schwind E, Karczeski B, Strecker MN, et al. Molecular testing for cystic fibrosis carrier status practice guidelines: recommendations of the national society of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(1):5-15. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9636-9.

- Gross SJ, Pletcher BA, Monaghan KG. Carrier screening in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Genet Med. 2008;10(1):54-56. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f247c.

- Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine--points to consider. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):653-662. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000666.

- Condit C, Templeton A, Bates BR, Bevan JL, Harris TM. Attitudinal barriers to delivery of race-targeted pharmacogenomics among informed lay persons. Genet Med. 2003;5(5):385-392. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000087990.30961.72.

- Shraga R, Yarnall S, Elango S, et al. Evaluating genetic ancestry and self-reported ethnicity in the context of carrier screening. BMC Genet. 2017;18(1):1-9. doi:10.1186/s12863-017-0570-y.

- Horn MEC, Dick MC, Frost B, et al. Neonatal screening for sickle cell diseases in Camberwell: Results and recommendations of a two year pilot study. Br Med J. 1986;292(6522):737-740. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6522.737.

- Davies SC, Cronin E, Gill M, Greengross P, Hickman M, Normand C. Screening for sickle cell disease and thalasaemia: a systematic review with supplementary research. Heal Technol Assess. 2000;4(3):1-99.

- Adjaye N, Bain BJ, Steer P. Prediction and diagnosis of sickling disorders in neonates. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64(spec no 1):39-43. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.1 Spec_No.39.

- Ormond KE, Mills PL, Lester L a, Ross LF. Effect of family history on disclosure patterns of cystic fibrosis carrier status. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2003;119C:70-77. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.10008.

- Nazareth SB, Lazarin GA, Goldberg JD. Changing trends in carrier screening for genetic disease in the United States. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(10):931-935. doi: 10.1002/pd.4647.

- ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 690: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. 2017;129(690):35-40. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001951.

- Counsyl. Counsyl Foresight. counsyl.com/provider/foresight-carrier-screen/. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Invitae. Carrier screening. invitae.com/en/physician/category/CAT000239/. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- Genpath. The pan-ethnic carrier tests from GenPath. genpathdiagnostics.com/womens-health/inherigen/. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- LabCorp. Inheritest carrier screening. labcorp.com/resource/inheritest-carrier-screening#. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- Natera. Horizon, Natera carrier screen. https://www.natera.com/horizon-carrier-screen.

- Beauchamp KA, Muzzey D, Wong KK, et al. Systematic design and comparison of expanded carrier screening panels. Genet Med. 2018;20(1):55-63. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.69.

- Azimi M, Schmaus K, Greger V, Neitzel D, Rochelle R, Dinh T. Carrier screening by next-generation sequencing: health benefits and cost effectiveness. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016;4(3):292-302. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.204.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevemtion. ACCE model process for evaluating genetic tests. cdc.gov/genomics/gtesting/ACCE/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- Parikh R, Mathai A, Parikh S, Chandra Sekhar G, Thomas R. Understanding and using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56(1):45-50.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine; How can consumers be sure a genetic test is valid and useful? https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/testing/validtest. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- Aziz N, Zhao Q, Bry L, et al. College of American pathologists’ laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing clinical tests. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(4):481-493. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0250-CP.

- Rehm HL, Bale SJ, Bayrak-Toydemir P, et al. ACMG clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15(9):733-747. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.92.

- Hogan GJ, Vysotskaia VS, Beauchamp KA, et al. Validation of an expanded carrier screen that optimizes sensitivity via full-exon sequencing and panel-wide copy number variant identification. Clin Chem. 2018;64(7):1-11. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.286823.

- Feero WG. Establishing the clinical validity of arrhythmia-related genetic variations using the electronic medical record: a valid take on precision medicine. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315(1):33-35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17346.14.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACCE model list of 44 targeted questions aimed at a comprehensive review of genetic testing. cdc.gov/genomics/gtesting/acce/acce_proj.htm. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Grody WW, Thompson BH, Gregg AR, et al. ACMG position statement on prenatal/preconception expanded carrier screening. Genet Med. 2013;15(6):482-483. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.47.

- Henneman L, Borry P, Chokoshvili D, et al. Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(6):e1-e12. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.271.

- Lazarin GA, Hawthorne F, Collins NS, Platt EA, Evans EA, Haque IS. Systematic classification of disease severity for evaluation of expanded carrier screening panels. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):1-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114391.

- Ghiossi CE, Goldberg JD, Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Wong KK. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: reproductive behaviors of at-risk couples. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(3):616-625. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0160-1.

- Franasiak JM, Olcha M, Bergh PA, et al. Expanded carrier screening in an infertile population: how often is clinical decision making affected? Genet Med. 2016;18(11):1097-1101. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.8.

- Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, Evans EA, Goldberg JD, Wapner RJ. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified by expanded carrier screening. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;316(7):734-742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11139.

- Arjunan A, Litwack K, Collins N, Charrow J. Carrier screening in the era of expanding genetic technology. Genet Med. 2016;18(12):1214-1217. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.30.

- Silver AJ, Larson JL, Silver MJ, et al. Carrier screening is a deficient strategy for determining sperm donor eligibility and reducing risk of disease in recipient children. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2016;20(6):276-284. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2016.0014.