- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Part I: The Promise of Telehealth – A Cautionary Tale

The rise of telehealth during COVID-19, its limitations, and its uncertain future.

FROM THE EDITORS: Neil Minkoff, MD, founder of FountainHead HealthCare and the chief medical officer of COEUS Consulting Group, died suddenly on May 4, 2022. Dr Minkoff was a longtime friend of and frequent collaborator with The American Journal of Managed Care® (AJMC®). His colleagues, Joshua Greenblatt, BFA, and Yana Volman, MBA, have worked with the AJMC® editorial team to complete this project: a 2-part series on the future of telehealth. The first part appears online today, and the second part will appear in the October issue of Evidence-Based Oncology™.

The massive pandemic-driven expansion of telehealth will have a consequential, enduring impact on the health care delivery system. However, telehealth’s future role in health care delivery is deeply uncertain in terms of its appropriate use across the stages of patient care, among myriad disease types and discrete clinical care needs, and amid uncertainty in payment and provider operational models.

Overall, telehealth has increased patients’ access to care, supplementing in-person visits for initial diagnosis and follow-up care. However, the pandemic-driven reliance on virtual visits has highlighted telehealth’s risks, which include potential misdiagnoses and recommendations of inaccurate treatment plans, as well as data security and privacy concerns. Provider reimbursement uncertainty and required investments into virtual care solutions have also impacted the consistency with which care is provided.

While telehealth usage seems to have peaked in 2020, the latest data suggest that we are now in a more permanent shift to a mixed care model, with telehealth use at a 38-fold increase over pre–COVID-19 levels.1

The unprecedented turn to telehealth holds much positive promise, but it is fraught with risk and challenges. While a return to the pre–COVID-19 care model is unlikely, a clear view of the way forward has not yet emerged.

Overnight “success.” Despite steady—albeit modest—growth in direct-to-patient telehealth prior to the pandemic, the more accepted and delivery system–friendly model for telehealth prior to COVID-19 had been physician-to-physician. This approach envisions telehealth expanding access, virtually, to highly specialized care (eg, a stroke patient presents at a rural hospital emergency department, and the local physician consults a stroke specialist via telehealth).

In the response to COVID-19, barriers to rapid adoption of direct-to-patient telehealth tumbled as providers, payers, policymakers, and technology vendors raced to enable robust use of virtual care to help prevent disease spread, while continuing needed care for patients. CMS led the way by adopting a telehealth-friendly reimbursement approach, thus exerting pressure on private payers to similarly shift to enable greater telehealth use.

Health care claims data and polling confirm the explosive growth in telehealth. In 2020, Medicare reported that 1.3 million people per week were using telehealth during the height of the pandemic; this included nearly 50% of all primary care visits.2

As the pandemic has subsided, telehealth usage has leveled off to about 23%; patients and physicians find it safer to resume in-person visits.3 But the transformative impact remains. According to polling by Change Healthcare and Harris, 3 in 4 consumers believed telehealth is the future of medicine; 80% said COVID-19 has made telehealth an indispensable part of the health care system.4 However, there are reports that some payers are starting to roll back coverage, albeit not to pre–COVID-19 levels.5

What’s Next for Telehealth and Care Delivery?

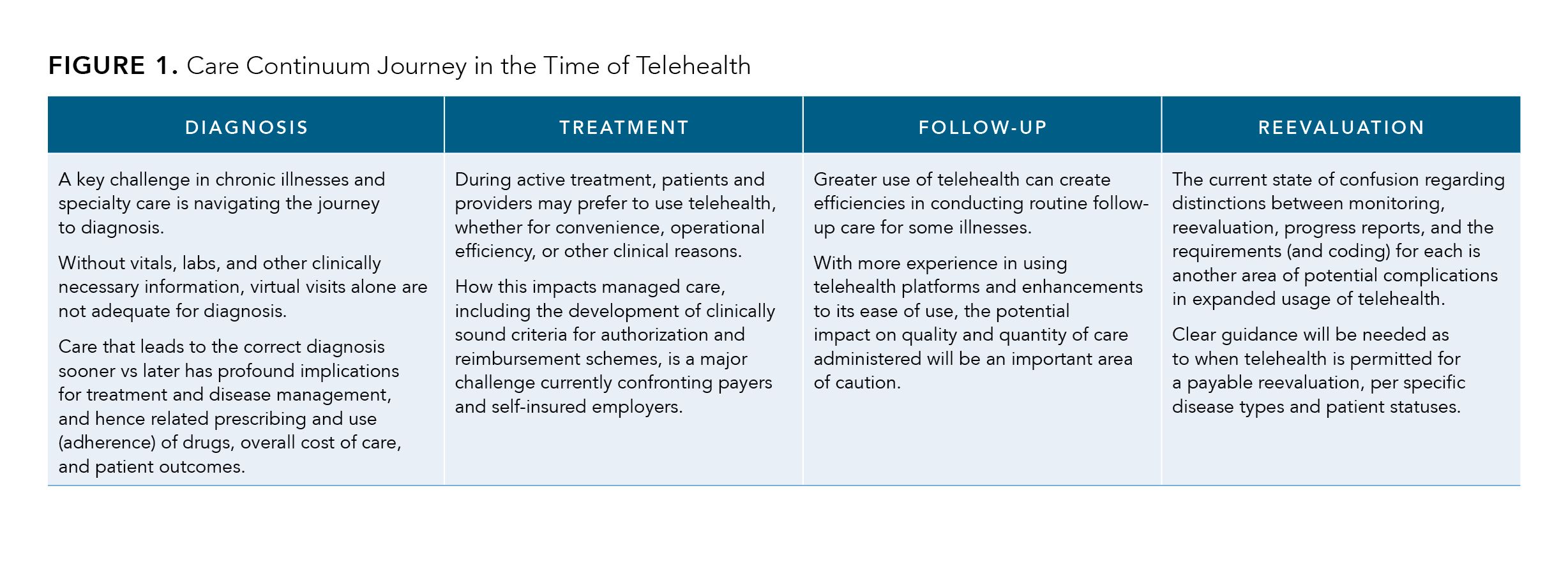

The future use of telehealth across the continuum of patient care—from diagnosis to active treatment, follow-up, and reevaluation—will have varied impacts on stakeholders, including payers, providers, pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, and employers (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (click to enlarge)

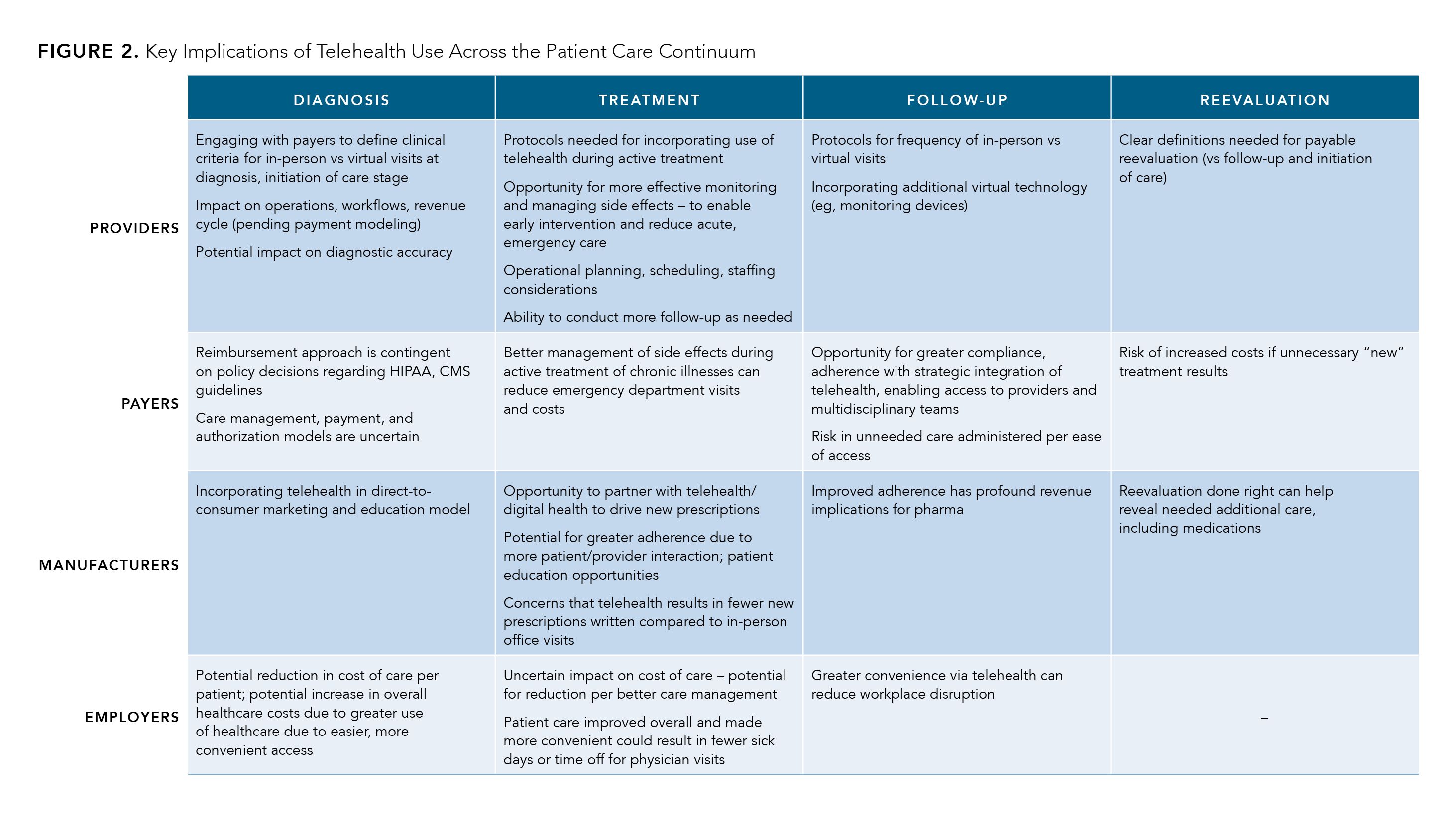

Overall, the implications for providers, payers, manufacturers, and employers are mixed (Figure 2), just as they are for the patients. On one hand, there has been an observed increase in the number of patient-provider interactions enabled by telehealth.6 Conversely, claims data analysis from health care industry intelligence and analytics firm IQVIA indicate that providers using telehealth are spending less time with patients, which may result in fewer new brand prescriptions.7

Figure 2. (click to enlarge)

Incorporating telehealth into a system that takes on the needs of patients with clinically complex, life-threatening, and/or chronic conditions is expected to increase, but with limitations. Proper diagnosis or follow-up for certain diseases may have varied success in a virtual environment. Let’s consider a few common diagnoses and the impact of telehealth on the patient journey in each:

Diabetes. In diabetes care, multiple studies of telehealth usage indicate significant clinical benefits, such as improved glycemic control. Convenience, especially for patients with ambulatory issues and/or those living in remote areas, was also reported as a major benefit.8

The Advanced Comprehensive Diabetes Care program from the Department of Veterans Affairs combined frequent virtual visits with clinicians and patient self-monitoring and data reporting.9 Patient outcomes include a measurable, long-term reduction in glycated hemoglobin. The analysis of study data confirmed that: “…intensive telehealth interventions are conducive to implementation and produce sustained improvements in glycemic control among rural patients.”

Applying this approach to a broad, general patient base would require significant planning and implementation, revamping reimbursement and authorization guidelines, and further cost/benefit analysis.

Multiple sclerosis. In multiple sclerosis care, the pandemic created a special opportunity to test the effectiveness of telehealth, and to consider the challenges in remotely conducting neurologic exams and performing triage for new patients. The benefits of telehealth in providing greater convenience and access to care, particularly for aspects of follow-up care, are significant. However, according to a report from the National Institutes of Health, clinical advantages achieved using telehealth are unclear. For example, results varied in several studies of whether home-based telerehabilitation improved the timed 25-foot walk. Also, performing a complete neurological exam cannot be done remotely, as illustrated by one particular study in which authors wrote10:

“There is still no reliable way for the remote neurologist to evaluate tone, sensation, reflexes, and fundoscopy via telehealth. This limitation poses a concern for potential misdiagnosis and mismanagement.”

Recognizing the benefits while acknowledging the need for more evidence-based research, the American Academy of Neurology recently asked federal lawmakers to approve a permanent expansion of telehealth, while noting the need to define reimbursement parity to avoid variability among states and insurers.11

Oncology. In oncology care, patients and providers responded positively to telehealth during COVID-19, notwithstanding obstacles such as technology literacy, broadband availability, and other access problems. A survey of physicians at a large community-based oncology practice pointed to important potential benefits of telehealth in managing cancer care longitudinally and achieving value-based care objectives.12 For example, reducing emergency department visits was a key quality measure in the Oncology Care Model, a flagship value-based care program from the CMS Innovation Center that concluded on June 30, 2022.

In the survey, conducted by Texas Oncology, “55% of respondents were using telemedicine to manage urgent patient issues, and 57% of those respondents believe an emergency department visit or hospitalization was avoided using telemedicine.”12

However, the impact of delayed screenings and other preventative diagnostics on cancer incidence, disease progression, patient outcomes, and total cost of care still remains to be seen.

Given the advantages, opportunities, and challenges in use of telehealth in patients with different complex conditions, questions remain:

- Will telehealth ultimately result in patients seeking and physicians delivering more care—more visits whether virtual or in person?

- Will this increase overall costs near term or, conversely, lead to better outcomes that reduce total costs?

Telehealth and the New Normal: Post–COVID-19 Implications

As an integrated, technology-enabled care option, telehealth is expected to continue at greater levels than before COVID-19. Given the pandemic experience, physicians and patients will expect to have greater opportunity to choose preferred and optimal methods of interaction.

Drivers of telehealth adoption include clinical appropriateness, convenience, access to care (eg, for rural patients), patient and provider acceptance, and favorable policy and reimbursement approaches.

More experience and study of telehealth usage outside of the recent public health emergency are needed to clarify its long-term impact and effectiveness. For now, discernable positive implications are:

Better care management. Virtual visits clearly are better than no visits. That is, patients with transportation issues or other challenges in accessing care (eg, ambulatory issues, work schedules, travel issues) are more likely to be seen as needed if telehealth is an option—and therefore are more likely to stay on course with treatment.

Patient compliance and monitoring. Telehealth-enabled visits with integrated care teams—physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers—can reinforce patient education, assist in better symptom detection and management of adverse effects, and support better medication adherence. This can enhance providers’ ability to meet value-based care performance goals, drive revenue for pharma, and improve patient outcomes.

Also, as greater adoption of remote health monitoring occurs, complementing virtual physician visits, aggregate data will provide valuable insights to inform future investments into research and development.

Provider efficiency. Telehealth offers potential for providers to operate more efficiently, possibly increasing the number of patient visits (blending virtual and in-person) to schedules, reducing no-shows and rescheduling, and improving patient experience and patient satisfaction.

Awareness and education opportunity. Increased acceptance of technology by patients and providers offers opportunities for pharmaceutical manufacturers to engage with patients and physicians to strengthen relationships and provide patient education and understanding of medications. Improving adherence also is a major potential benefit.

The most current thought leadership on telehealth points to significant benefits and promise. But telehealth is not a panacea for all that ails the health care system. Challenges that remain are significant and may not be overcome with increased access to physicians via telehealth platforms.

Clinical care implications. Large-scale research into clinical outcomes from telehealth usage is limited. It is a complex challenge to develop evidence-based criteria and protocols, and to create and implement guidelines for appropriate use of telehealth, integrated with in-person visits and across multiple disease types and stages. On behalf of their patients and other stakeholders, providers will need to guard against “bright shiny object” syndrome in telehealth, as a New York Times columnist, a former emergency department physician, Elisabeth Rosenthal, MD, recently warned:

“COVID-19 let virtual medicine out of the bottle. Now it’s time to tame it. If we don’t, there is a danger that it will stealthily become a mainstay of our medical care. Deploying it too widely or too quickly risks poorer care, inequities and even more outrageous charges in a system already infamous for big bills.”13

Technology issues. Gaps in broadband access, a barrier to entry for use of telehealth, will not be filled immediately. Tech savviness and access to devices for patient populations who trend older for some diseases (eg, cancer) or have lower incomes will continue to be a challenge.

Virtual visits alone—absent complementary tracking and monitoring technologies—can limit the benefits of telehealth while also missing the opportunity to produce data, at scale, that will inform continued improvement and optimization of care. How to develop, apply, and fund these technologies is critical to delivering the greatest value from telehealth.

Unknown economic impact. The impact of greater use of telehealth on the cost of care is unclear. While convenient access to clinical teams can mean better care overall, it also could result in more care. Efficiencies in clinical operations may be offset by increasing care consumption and changing expectations among patients-as-consumers.

New rules matter. The policy/regulatory and reimbursement scheme surrounding telehealth is in flux as policymakers and stakeholders emerge from the pandemic. Which stakeholders win or lose the many discrete and arcane rulemaking battles to come will have profound impact on telehealth adoption. Already, some states are rescinding executive orders and other policies, causing new complications in care delivery, particularly in cases where patients get care from physicians in more than 1 state. This hints of the greater complexities on the horizon in the state-by-state patchwork policy environment.

Deciding what stays, goes, or evolves is a daunting, complex challenge facing policymakers, patient advocates, payers, and all stakeholders. The future of key measures implemented on a temporary basis by federal and state governments and payers during COVID-19 will be key:

- Waiving HIPAA requirements to allow use of FaceTime and Skype for virtual patient visits

- Relaxing controlled substances’ prescribing requirements (no in-person visit required)

- Opening telehealth to all geographies, not just rural areas, and allowing use of smartphones and virtual visits from patients’ homes

- Reducing or eliminating cost sharing for telehealth care

- Allowing telehealth for certain dialysis patient visits (Medicare)Regulating service parity and payment parity (per

Conclusions

The health care delivery system is characterized by overpowering institutional, regulatory, and business model biases against change. But with the pandemic, circumstances beyond the grasp of usual controls forced a dramatic acceleration in telehealth usage.

A new patient/health care consumer experience paradigm has begun, along with a quantum leap in acceptance and understanding among patients, providers, policymakers, and payers that flowed from the increased usage.

Opportunities and benefits—such as better medication adherence, convenience for location- or mobility-challenged patients, and greater access to needed care—are notable. Overcoming access and technology challenges, understanding and mitigating risks in clinical care, and achieving consensus among health care stakeholders on a comprehensive approach going forward will be front and center in the coming months and years.

Author information

Neil Minkoff, MD, served as chief medical officer at COEUS Consulting Group and was a senior physician leader at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. Joshua Greenblatt, BFA, is the chief business officer of COEUS Consulting Group. Yana Volman, MBA, is the senior vice president of access strategy and communications with COEUS Consulting Group.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Edward Bryson for editorial assistance.

References

1. Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, Rost A. Telehealth: a quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey & Company. July 9, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

2. Pifer R. Dive Brief: Medicare members using telehealth grew 120 times in early weeks of COVID-19 as regulations eased. HEALTHCAREDIVE. May 27, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/medicare-seniors-telehealth-covid-coronavirus-cms-trump/578685/

3.Karimi M, Lee EC, Couture SJ, et al. National survey trends in telehealth use in 2021: disparities in utilization and audio vs. video services. US Department of Health and Human Services; Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; Office of Health Policy. February 1, 2022. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/4e1853c0b4885112b2994680a58af9ed/telehealth-hps-ib.pdf

4. The 2020 Healthcare Consumer Experience Index. Change Healthcare. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.changehealthcare.com/insights/healthcare-consumer-experience-index

5. LaPointe J. States make progress with telehealth reimbursement laws. Revcycle Intelligence. February 15, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/states-make-progress-with-telehealth-reimbursement-laws

6. Spatz I, Augenstein J. Telehealth boom times during COVID-19: implications for pharma. Lexology. June 3, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=42cf677c-1879-4207-9eb6-9e7919d78748

7. Dolan A. Telehealth transformation: moving from crisis response to population health solutions. IQVIA. November 16, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/library/publications/telehealth-transformation

8. Rodriquez T. Telemedicine for diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Endocrinology Advisor. April 27, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.endocrinologyadvisor.com/home/topics/diabetes/telemedicine-for-diabetes-management-update-and-interviews/

9. Kobe EA, Lewinski A, Danus S, et al. Implementation of an intensive telehealth intervention for rural patients with uncontrolled diabetes. Presented at: The American Diabetes Association 80th Scientific Sessions; June 12-16, 2020; virtual. https://plan.core-apps.com/tristar_ada20/abstract/b1aeadfb-e8c8-4d08-8434-f59df4464907

10. Xiang XM, Bernard J. Telehealth in multiple sclerosis clinical care and research. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021;21(4):14. doi:10.1007/s11910-021-01103-4

11. Hatcher-Martin JM, Busis NA, Cohen BH, et al. American Academy of Neurology telehealth position statement. Neurology. 2021;97(7):334-339. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012185

12. Patt D, Wilfong L, Kanipe K, Paulson RS. Telemedicine for cancer care: implementation across a multicenter community oncology practice. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(10 Spec No):SP330-SP332. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.88560

13. Rosenthal E. Telemedicine is a tool. not a replacement for your doctor’s touch. The New York Times. April 29, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/29/opinion/virtual-remote-medicine-covid.html

Subjective and Objective Impacts of Ambulatory AI Scribes

January 8th 2026Although the vast majority of physicians using an artificial intelligence (AI) scribe perceived a reduction in documentation time, those with the most actual time savings had higher relative baseline levels of documentation time.

Read More