- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

OCM Practices Struggle with CMS Report Cards

When the CMS released performance reports for the 181 practices enrolled in the Oncology Care Model (OCM) earlier this year, the action had the effect of creating as much confusion as it resolved.

When the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released performance reports for the 181 practices enrolled in the Oncology Care Model (OCM) earlier this year, the action had the effect of creating as much confusion as it resolved. Practices were looking forward to finding out whether they qualified for bonus payments for exceptional performance. What some found out, however, was that they had to pay money back to CMS. Now, as participating practices anticipate the second round of performance reports, due at the end of August, they hope things will go more smoothly.

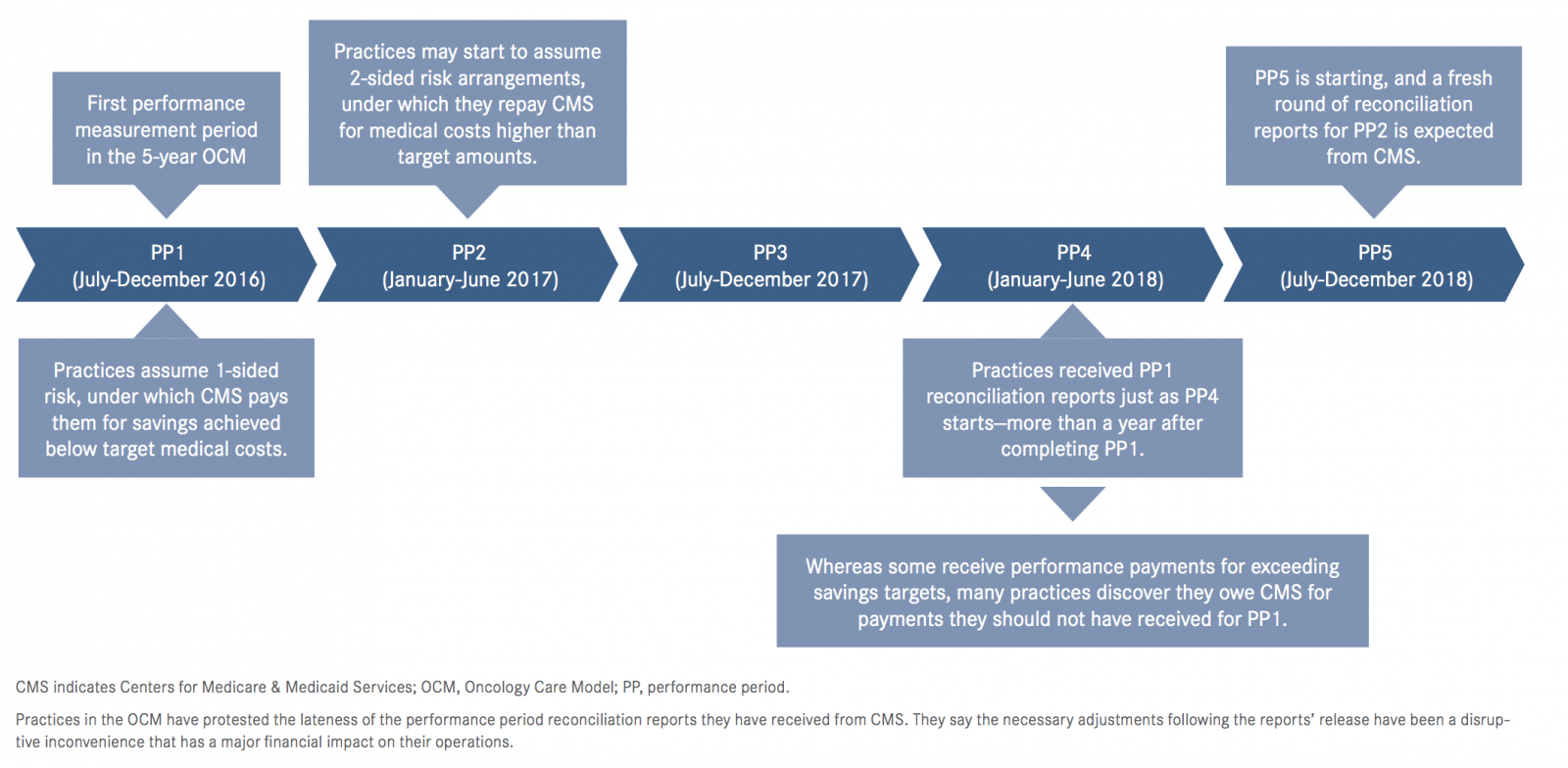

Two years into the OCM pilot, practices in February received their performance period 1 (PP1) reconciliation reports—detailed accounts regarding the 6-month period from July to December 2016 when the 5-year OCM pilot was initiated. Some practices were unhappy with not only the reports’ conclusions and the methodology used by CMS but also the fact that they learned their full PP1 results just as period 4 got under way.

“You don’t know how you’re going to be judged, and you just got the results from more than a year ago,” said Bo Gamble, director of strategic practice initiatives for the Community Oncology Alliance (COA). “It’s so complicated, people can’t make timely, conscious decisions about how to improve their care while lowering costs.” The OCM is a patient-centric program that CMS says will allow for “better care, smarter spending, and healthier people.” It aims to move practices from volume-based to value-based care by structuring Medicare payments around the full range of services an oncology patient needs. A practice that can both provide good treatment and spend less money than Medicare expected will be financially rewarded.

Other requirements for participating practices include giving each patient a 13-point care plan, recording patient information in a central database, and offering patients aroundthe- clock access to a clinician who can access medical records quickly. CMS provides monthly enhanced oncology services (MEOS) payments of $160 per patient per month to help practices institute necessary changes. The bulk of savings is expected to come from fewer hospital stays and emergency department (ED) visits and better use of hospice and palliative care options.

Figure. CMS' Timing of Performance Reconciliation Reports has Caused Adjustment Difficulties for Practices

Performance Payments

Barbara McAneny, MD, a managing partner of New Mexico Oncology Hematology Consultants Ltd and president of the American Medical Association, said her practice was among those that received a $23,000 performance-based payment for achieving savings below the targets set by CMS.

About 25% of participating practices received such payments, according to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI); however, COA estimates that those particular practices account for just 10% to 15% of patients and doctors. Gamble said that based on an informal COA poll, just 15% of responding practices received performance-based payments.

Although practices were happy to receive performance-based payments, many were dismayed to find that they had to return MEOS payments, which oncologists receive only if they are their patients’ primary care physicians. When patients see other physicians for health issues, CMS assigns or “attributes” the patient to the doctor who provided the most in-office care. CMS calculated that some oncologists had not served as primary care providers and asked for the money back. Some practices successfully appealed and got the MEOS payment cuts reduced.

Terrill Jordan, president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Regional Cancer Care Associates, which has 110 physicians and 30 local offices in Maryland, New Jersey, and Connecticut, said that about 27% of the network’s patients were attributed to other doctors. After an appeal to CMS, that figure fell to about 16%. “We provided coordinated care to a large group of patients who were not attributed to us, and we did not get full payment for this work,” Jordan said. “You can imagine our discomfort with that result.”

McAneny’s practice had to return $11,000. Even with the performance-based payment, she said, losing the MEOS funds for patients who’d received her practice’s treatment was a tough hit financially. She believed her practice qualified for a performance- based payment in part because it was already doing much of what the OCM required, she said. Still, making the switch to the OCM was costly; to meet the electronic health record requirements, the practice had to pay a large amount of overtime to staff members. “If we truly added up what it cost to do this model, the MEOS payments were insufficient,” she said.

She also contends the formula Medicare uses to determine an individual patient’s care costs does not adequately address rising drug prices or new therapies. McAneny said this discourages physicians from using expensive drugs and punishes those who take on patients with more complex health problems.

“If you came in with a melanoma and I treated you with standard old chemotherapy, you’d be dead in 3 months,” McAneny said. “If I treat you with the new expensive drug that costs $100,000 per year, you could live for years. Not to use that drug would be unethical, but I would get punished [financially]. If I get a lot of people who are inexpensive to take care of, then I look like a genius because I saved money. If I go over the target, I’m a bad doctor and I’m losing money.”

Support for the Program

Problems aside, many stakeholders said they remained enthusiastic about the program and wanted to see it succeed. Gamble of COA, the peerto- peer support organization working with 80% of the practices participating in the OCM, said his organization has sent 2 letters to CMMI describing concerns with the model. The issues included complicated errors in the performance methodology, excessive delays in the receipt of periodic report cards, and calculation errors. CMMI has made some of the requested changes to the model.

Although some practices are frustrated, Gamble said, COA continues to support the model and the teams involved. The primary goal is to improve the care for patients with cancer “as it should be,” he said. “Could it be going smoother and better? Yes. We need to work together to make it better. When we do that, others will be knocking on the door to get into this program.”

Charles Saunders, MD, is CEO of Integra Connect, which works with approximately 700 oncologists as a consultant and technology provider in the OCM. Some practices were asked to return 30% or more of their MEOS payments—“a major blow,” he said.

“Most [practices] buy into the concept but are expressing concern about its implementation,” Saunders said. “CMS needs to make some tweaks and modifications to the program to evolve it and improve it, and practices need to learn from the first performance period.”

One important change would be increasing transparency, according to Saunders. “There’s such a lag between the feedback and the performance period [that] it’s almost too late to make adjustments. If a practice did not bill for some of its eligible, attributed patients, in many cases it’s [now] too late to bill for them,” he said. “Practices need to move toward the ability to track and make adjustments in real time.”

Alyssa Dahl, MPH, manager of healthcare data analytics at DataGen, said the company has about 19 practices participating in the OCM. Most were not expecting to achieve any savings or receive a performance-based payment in the first reconciliation period because of the administrative work required, yet some did. Because of client confidentiality, she did not share exact numbers. “Most were saying, ‘We’re lucky if we can break even and wouldn’t have to owe anything,’” she said. “Nobody was expecting to make money, and those that did were pleasantly surprised.”

Many DataGen practices remain enthusiastic about the program because they see it as “giving them a framework to enhance and transform how they practice oncology and do the right thing for patients,” Dahl said. “They say, ‘We were never required to have a 24/7 clinician access, and this gives us the framework to do that.’ They see the impact that can have when patients come to the extended hours oncology clinic instead of going to the emergency department. They can do the right thing for the patient and give them better treatment immediately instead of having them go through other care settings before their immediate cancer needs are addressed.”

Cost of Investment

Jordan said that the OCM required his network to invest in care coordination, triage, and analytics software and hire 20 program professionals, such as a vice president of clinical affairs, nurse managers, and other support staff. He didn’t expect to receive a performance-based payment, and he did not. “It took between 6 [and] 9 months, maybe even longer, to put it all in place,” Jordan said.

The OCM is a new and challenging program and, as rolled out, is quite comprehensive, Jordan noted: “The level of deep thought and hard work put into planning the program was evident.” He sees room for improvement, however. The formula for determining target costs for certain types of cancers needs to be revisited, he said. Bladder cancer, for example, often costs more to treat than the OCM target. “Fortunately, CMS is listening,” he said.

Jordan said that he believes value-based programs are the future of oncology, and the network’s patients are getting better care—ED visits and hospital admissions have decreased, and clinicians are considering hospice care earlier. “We made progress on many fronts [in PP1], yet we can do more,” he concluded.

CEO Robert Baird said that Dayton Physicians Network did not receive a performance-based payment and, in fact, had to surrender MEOS payments for hundreds of patients who were not attributed to the practice. Still, he believes that OCM offers a better way to care for patients and the savings will come in time. “It’s brought some positive changes to oncology practices,” he said. “Since it’s Medicare, we were plugging along, making changes but having a hard time moving the ball forward.”

The practice had some of the infrastructure needed to meet the OCM’s demands in place before the program began because it has participated in other trials, including the Oncology Medical Home program. But the network still needed to hire more information technology employees and more medical staff, including nurse practitioners for survivorship and palliative care. An outside consultant was brought in to manage data. The practice also partnered with hospice and palliative care programs. “These were some of the programs we were already doing, but we really kicked it up a notch,” Baird said.

Although the PP1 revealed areas that needed improvement, Baird said some of the issues were already being addressed. For example, PP1 showed a high number of ED visits and hospital stays, but for the past 1½ years, Dayton Physicians Network has been working to educate patients on the importance of calling their doctor first. They’ve addressed this issue in print ads, on television, and on posters in their offices. Staff members wear buttons promoting the idea and make a point of stressing the need to patients.

Because of those efforts and others, Baird believes his practice will show more success in its third performance period report. Instead of being unhappy with their PP1 results, Baird said, his physicians and staff members were excited about moving forward. “I think it really opened their eyes to how payers are measuring us and how that calculates into reimbursement,” he said. “It motivated everybody to say, ‘This is real. This is happening.’”

During the first performance period, practices shared only upside risk with CMS, meaning that if their medical costs exceeded the targets set by CMS they would not be held responsible. It is CMS’ goal to eventually have all practices assume downside risk as well, and in subsequent performance periods that has been voluntary. CMS did not respond to a request for the number of practices, if any, that have assumed downside risk so far. However, Gamble said that to COA’s knowledge, none have.

Originally published by Onc Live as "Practices Struggle With Oncology Care Model Report Cards."

NAACOS Continues Pushing Forward on the Transition to Value-Based Care

September 21st 2020Allison Brennan, MPP, discusses legislation that would affect accountable care organizations (ACOs), the impact coronavirus disease 2019 had on ACOs, and the fall National Association of ACOs meeting.

Listen

Examining Physician-Initiated Alternative Payment Models, a New Wave of Payment Reform

September 12th 2019To date, most alternative payment models (APMs) that have emerged in the shift toward value-based care have been initiated by payers and focused on primary care providers. However, there has recently been a new wave of payment reform in which providers, mostly specialists, are designing and implementing their own APMs in their practices. A study published in the September issue of The American Journal of Managed Care® analyzed some of these new payment models to gain insight into what providers are prioritizing in their APMs.

Listen