- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Lowering Out-of-Pocket Costs for Older Adults: A Guide

A Review of Available Federal Assistance Programs and Patient Resources

This is sponsored by Lilly USA, LLC and the sponsor has sole editorial control.

When older adults move to Medicare coverage, they may face challenges with out-of-pocket medical costs because of the shift to a fixed income that often comes with retirement. These costs can be especially high among older adult patients with diabetes, who often require multiple medications and self-management supplies to not only achieve glycemic control, but also to manage conditions related to general aging and comorbidities. Although there are programs and resources to help with these costs, many patients and providers are not aware they exist. This publication will show how providers can help their patients with Medicare lower the out-of-pocket costs of their diabetes medications and connect them with assistance, when needed. The information contained herein includes interviews with key stakeholders involved in the care of older adults with diabetes who provide valuable insight into the affordability issues this population faces, the programs that are available for those who qualify, and counseling points for discussions with patients. A tear-off or ready-to-print checklist, which includes patient resources, is also included to aid in the process.

Financial Impact of Chronic Disease on Older Adults

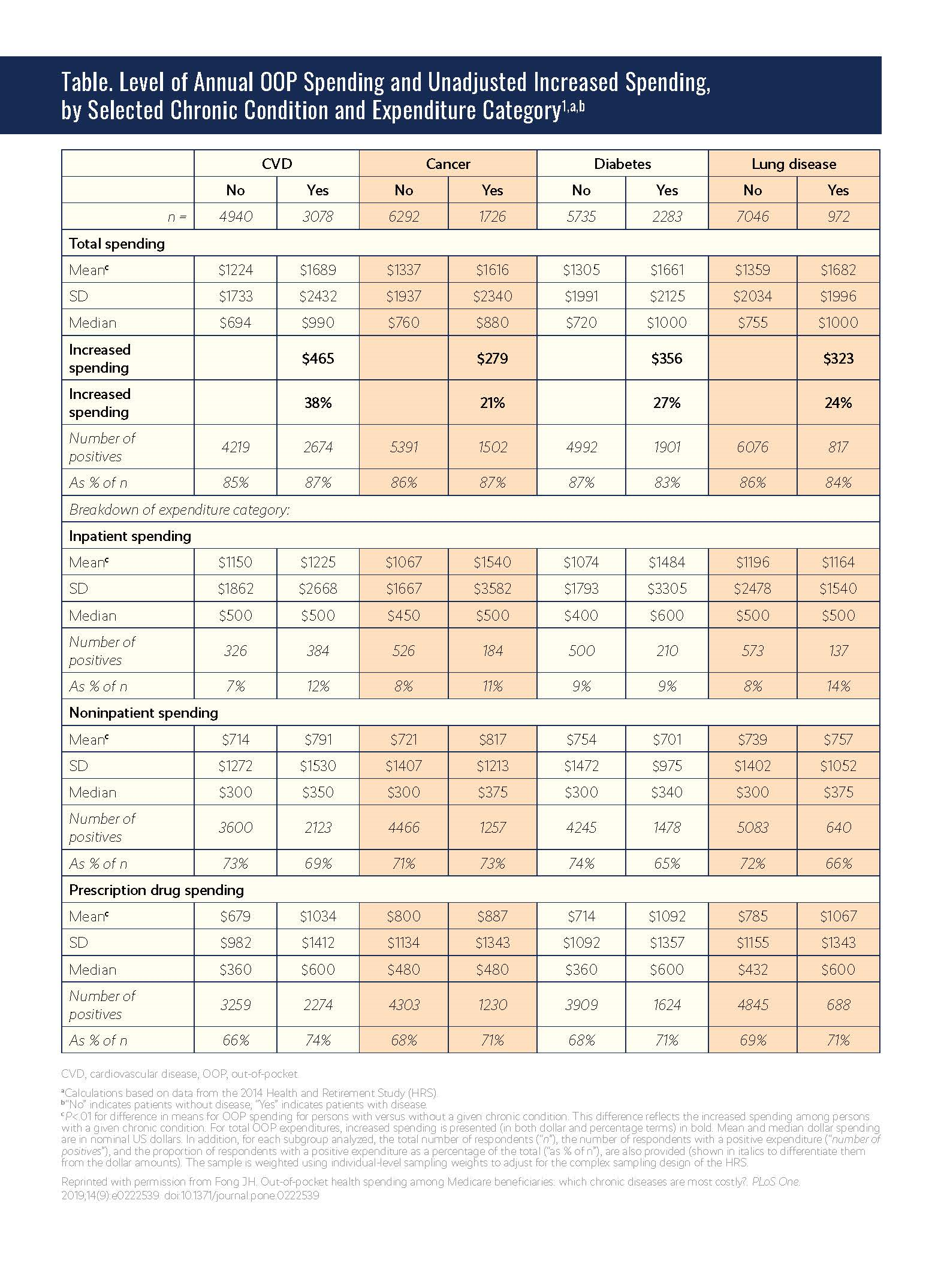

Chronic conditions common among older adults, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes, place a large economic burden on patients and the US health care system (see Table. Level of Annual OOP Spending and Unadjusted Increased Spending, by Selected Chronic Condition and Expenditure Category).1 Approximately 80% of older adults in the United States have 1 chronic disease and about 50% have 2 or more.2 Chronic diseases account for approximately two-thirds of all health care costs3 and 94% of Medicare spending.4

A prevalence-based analysis from the American Diabetes Association showed that an estimated $327 billion was spent on management of diabetes in 2017. Approximately $237 billion was spent on direct health care expenditures, with about $146 billion of that spent on individuals 65 years or older. Compared with their younger counterparts, older adults with diabetes had substantially higher costs related to prescription medications ($49.5 billion vs $21.7 billion), physician office visits ($20.4 billion vs $9.6 billion), and hospital inpatient care ($44.8 billion vs $24.8 billion), among other areas. Individuals diagnosed with diabetes incurred medical expenditures that were 2.3 times higher than for a population of age- and sex-matched individuals without the disease in 2017. Additionally, overall and excess medical costs per person with diabetes increased by 26% and 14%, respectively, from 2012 to 2017 after adjusting for general inflation.5

Click to view larger image.

The prevalence of diabetes among older adults is particularly high. Approximately 14.3 million individuals 65 years or older were predicted to have diabetes in 2018,6 and the results of the previously discussed analysis by the American Diabetes Association estimated that the average annual excess expenditure for older adults with diabetes was $13,239 (vs $6675 for their younger counterparts) in 2017.5 The results also indicated that approximately 61% of all diabetes-related health care expenditures were from patients 65 years or older.

Role of Medicare Part D in Prescription Drugs

Over 52 million beneficiaries 65 years or older have health insurance coverage from Medicare, and 40.2 million of those with Medicare coverage receive subsidized access to drug insurance coverage through Medicare Part D.7 Individuals are able to receive prescription drug coverage via the Medicare (PDP) (Part D) or a Medicare health plan that offers Medicare prescription drug coverage (eg, a Medicare Advantage plan).8 Of Part D enrollees in 2019, approximately 46% had standalone PDPs, 39% had Medicare Advantage plans, and 15% had employer or union group plans.9

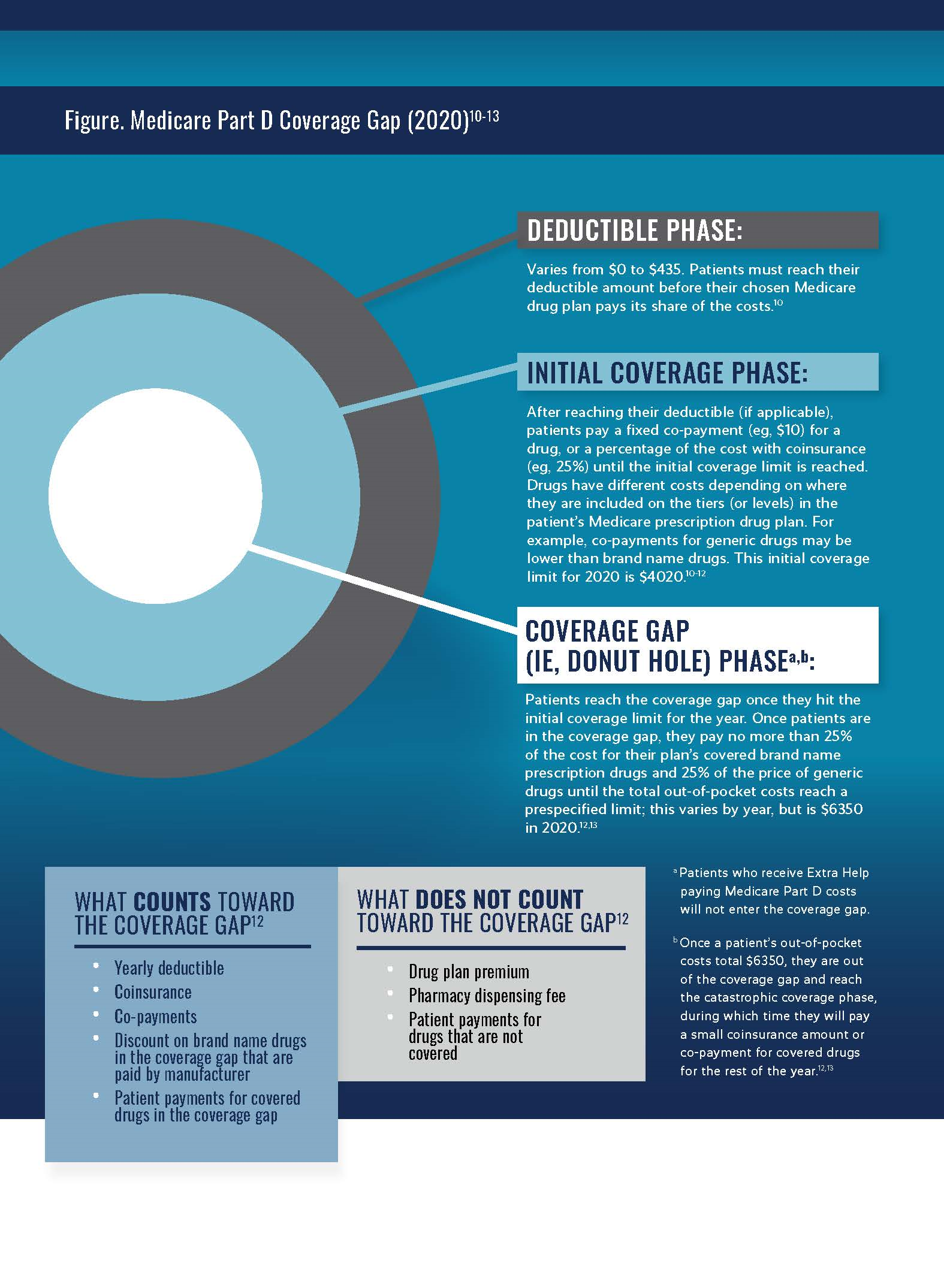

Outpatient medications, such as those for diabetes, are generally covered under Medicare Part D, but patients enter a coverage gap (commonly referred to as the “donut hole”) after the patient and drug plan spend a certain amount ($4020 in 2020) for covered drugs during the deductible and initial coverage phases (see Figure. Medicare Part D Coverage Gap (2020) for an overview).10-13 During the coverage gap, patients pay no more than 25% of the cost for their plan’s covered brand name prescription drugs and 25% of the price of generic drugs until the total out-of-pocket costs reach a prespecified limit; this varies by year, but is $6350 in 2020.12,13 After the OOP cost reaches $6350, patients enter the catastrophic coverage phase, in which they pay 5% or $3.60 for generic and preferred multisource drugs (whichever value is greater) or 5% or $8.95 for brand name medications (whichever value is greater).13 The out-of-pocket costs include the yearly deductible, coinsurance, co-payments, discounts on brand name drugs in the coverage gap, and what patients pay in the coverage gap. Out-of-pocket costs do not include the drug plan premium, pharmacy dispensing fee, or patient payments for drugs that are not covered by the PDP.

Click to view larger image.

This coverage gap may introduce high out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, who account for approximately one-third of all beneficiaries. Over 3.3 million Medicare beneficiaries use 1 or more common forms of insulin, and uninterrupted access to insulin is often critical for effective medical management and prevention of serious diabetes-related complications like vision loss, kidney failure, foot ulcers, and heart attacks.14

“Diabetes is one of the hardest chronic diseases to manage. Cost is clearly an issue [that contributes to the challenge], but it is only part of the issue. I think we’ve done a tremendous job helping patients manage their disease [so far], but we need to get patients on insulin earlier and help them stay there.”Neil B. Minkoff, MD

Founder

Fountainhead HealthCare

Impact of Out-of-Pocket Costs

OOP costs for diabetes management can have a notable financial impact on older adults with diabetes. Patients often require multiple medications to achieve glycemic control and manage conditions related not only to diabetes, but also general aging (eg, hypertension, hyperlipidemia). In addition to medications used to manage diabetes (eg, insulin) and related comorbidities, substantial costs are incurred through self-management supplies (eg, glucose testing meters, strips, continuous glucose monitoring), eye and foot care, and frequent physician and hospital visits.

These high costs raise concerns about the lack of affordability of health care and long-term health outcomes for many older adults. “Cost is 1 of the top 3 challenges older adults are facing regarding access to treatment for diabetes. A growing number of patients with diabetes are finding it difficult—if not impossible—to afford the treatments that they need,” according to Leigh Purvis, MPA, director of Health Care Costs and Access at AARP. “Coverage and adherence are the other 2 main challenges. There is a great deal of variability in health care coverage, which can have a huge impact on patients’ ability to access and afford necessary treatments. Furthermore, diabetes treatment can be complicated to follow. In combination with cost concerns and a variety of other factors, it can be very challenging for patients to remain adherent to their treatment regimens.”

Cost sharing in health insurance plans has also increased in recent years and has been associated with reductions in essential care visits, medications, and self-care supplies for patients with limited income. The results of a 2012 literature review found that 56 of 66 studies showed a substantial relationship between increased patient cost sharing and decreased medication adherence.15 In another study, results showed the use of essential drugs decreased by 9.14% after the initiation of a prescription coinsurance and deductible cost-sharing policy based on an interrupted time-series analysis of a random sample of 93,950 older adults.16 Furthermore, the results of a retrospective claims analysis of data from 35 large, private, self-insured employers from 2004 to 2012 showed that a $10 increase in OOP cost for a prespecified bundle of type 2 diabetes prescriptions was associated with a 1.9% decrease in adherence.17

Results of this study also showed that increasing the average OOP cost per prescription from $10 to $50 was associated with a $242 decrease in per patient payer costs for type 2 diabetes prescriptions and a $342 increase in per patient hospitalization costs (ie, a net $100 increase in plan costs).17 “The median income for Medicare beneficiaries is just over $26,000 per year and they typically have limited savings. Meanwhile, the prices of many diabetes treatments have increased considerably over the past several years,” Purvis [AARP] said. “This situation has forced an increasing number of older Americans to choose between paying for expensive diabetes drugs and other needs like food and rent. It is also important to keep in mind that diabetes is a chronic condition, so treatment is not a 1-time financial hardship—patients will face these challenges for the rest of their lives.”

The challenges can have devastating consequences. According to Campbell Hutton, vice president, Regulatory and Health Policy (JDRF International), “The biggest tragedy is when you read stories about a patient who has died because of the lack of insulin [or] because they’re rationing it. It is important that information about programs that can help in these cases reaches more people so they can take advantage of them.”

Having a health insurance plan well suited to a patient’s medical and income needs can help ease the economic burden of managing diabetes; however, navigating the complexities of health insurance can be particularly difficult for older adults. “One of the things I have noticed across a number of different organizations and populations of patients with whom I have worked is that part of the confusion among patients and providers is around where to go to get the information they need,” said Neil B. Minkoff, MD, former senior medical director, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, and founder of Fountainhead HealthCare.

Minkoff [Fountainhead] further explained that the onus of providing care and education for patients with diabetes is splintered among endocrinologists, primary care providers (PCPs), and the hospitals with whom they work. “The first source of information for the patient is often the provider who looks after their main diabetes care—a PCP or endocrinologist; however, providers themselves may not be aware of the options that exist for their patients. Furthermore, if a patient goes to the hospital, how will the education provided by the endocrinology department differ than what is provided through their PCP?” The average Medicare beneficiary had a choice of 28 PDPs in 2020, and plans range widely in terms of premiums, deductibles, and cost sharing.18

“Increasing enrollment in programs like the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy and Medicare Part D Senior Savings Model can go a long way toward reducing out-of-pocket expenses, including premium paymentsfor Part D plans.”David Lipschutz, JD

Associate Director

Center for Medicare Advocacy

According to the results of an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), the average premiums for the 20 PDPs available nationwide ranged from $13 to $83 per month for 2020 plans. These premiums can change annually because of plan alterations and consolidations. Two-thirds of Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies were expected to have increases in their monthly premiums if they stayed on the plan they had in 2019, and 20% of beneficiaries who receive the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy would pay Part D premiums in 2020 if they kept the same plan, even though these individuals are eligible to receive premium-free Part D coverage.18

Assistance Programs for Older Adults Exist, but Patients and Providers Are Unaware

Patients with limited income may be eligible for federal assistance programs, such as the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy program, the Part D Senior Savings Model (which will take effect January 2021), or patient assistance programs through drug and device manufacturers, state programs, and patient advocacy organizations. These types of programs can greatly help patients in need of assistance; however, many individuals who qualify for these programs are not aware they exist.

“Many of the patients with diabetes we encounter are totally unaware that they can get help either with their Medicare premiums or Medicaid.”Susan Nolan

Affordable Care Act Navigator

Legal Services of Northern Virginia

“As patients approach age 65, they receive a letter from Social Security saying they need to apply for Medicare either 3 months before or 3 months after their 65th birthday month. Somewhere in that letter, it will say, ‘If you are a low-income Medicare recipient, you may be able to get help from Medicaid with your costs.’ It is a vague statement and people do not pick up on it or they do not even understand what it means.” according to Susan Nolan, an Affordable Care Act navigator and paralegal at Legal Services of Northern Virginia (LSNV). “They [end up] enrolling in Medicare, paying for Part B, and come to find out their benefits are $1100 a month and they are losing $144.60 of that [amount] to Part B premiums. [The patient is not going to be aware of it unless] they meet with a Medicare counselor, and I am sure that providers’ offices are not aware of it unless they are involved in billing. There is a lot of confusion about this program.”

In addition, many health care providers are not aware of the programs that exist for their patients. “[Many] providers do not get involved except to say, ‘We accept your insurance,’ or ‘We do not accept your insurance,” Nolan [LSNV] said. Not only does this lack of provider awareness impact those who are already familiar with the US Medicare system, but it also impacts those individuals who have immigrated into the country and are unaware of how Medicare works. According to Nolan [LSNV], “We have encountered immigrants who have been working in this country for 20 to 30 years and they receive the [Medicare enrollment] card in the mail one day and they have no idea what it means. They do not understand what Medicare is to begin with, let alone that when you turn 65, you are Medicare eligible. [As a result,] we find people who are enrolled in 2 different programs.”

Minkoff [Fountainhead] explained that although Medicare Advantage is putting several programs into place around education on a population basis and on a Medication Advantage service provider level, it is important to recognize that patients may not remain with the same Medicare Advantage plan year after year. “Older adult patients with diabetes and comorbidities are more likely to remain with the same PCP,” Minkoff said.

Thus, the need to increase awareness of these programs among older adults and health care providers cannot be overstated. A more detailed description of the available programs and ways they can help older adult patients who qualify is discussed next.

“Sponsors participating in the Part D Senior Savings Model will offer beneficiaries plan choices that provide broad access to multiple types of insulin, marketed by Model-participating pharmaceutical manufacturers, at a maximum $35 co-pay for a month’s supply in the deductible, initial coverage, and coverage gap phases of the Part D benefit. As a result, beneficiaries who take insulin and enroll in a plan participating in the Model should save an average of $446 in annual out-of-pocket costs on insulin, or over 66%, relative to their average cost sharing today.

This predictable copay will provide improved access to and affordability of insulin in order to improve management of beneficiaries who require insulin as part of their care.”CMS Spokesperson

Medicare Part D Senior Savings Model

Because the cost of insulin can be a barrier to management of the disease, in March 2020, CMS introduced the Part D Senior Savings Model, a voluntary model that offers more choices of enhanced alternative Part D plan options that ensure a 30-day supply of a broad set of plan formulary insulins costs no more than $35 during the deductible, initial coverage, and coverage gap phases of Part D.14 According to CMS, the Part D Senior Savings Model builds on steps the Trump Administration has already taken to strengthen Medicare and improve the quality of care for patients with diabetes.14 The Model was created to fix a current market disincentive and provide predictable, affordable co-pays for the broad set of insulins that beneficiaries use today to prevent avoidable long-term quality of life and health complications. At a high level, CMS is enabling health plan innovation in order for Part D sponsors to offer beneficiaries lower out-of-pocket costs for the broad set of formulary-plan insulins.19 Although Part D sponsors may currently offer PDPs that provide lower cost sharing for brand name and other applicable drugs in the coverage gap, if a Part D sponsor chooses to enhance its benefit that way—due to the statutory “Special Rule for Supplemental Benefits” that is part of the law that created the manufacturer coverage gap discount program—the Part D sponsor would accrue costs that pharmaceutical manufacturers would normally pay. Those costs are then passed on to beneficiaries in the form of higher supplemental premiums.

Because Part D sponsors compete to offer Medicare beneficiaries affordable prescription drug coverage, only a few sponsors design a benefit that has supplemental benefit coverage for brand or other applicable drugs in the coverage gap. Given that brand name and other applicable drugs are the set of medications that often cost beneficiaries the most, beneficiaries end up paying 25% of the negotiated price, which closely mirrors the list price, in the coverage gap. That amount is often substantially higher than in the initial coverage phase and can represent a financial burden for Medicare beneficiaries.14

The innovation being tested through the Part D Senior Savings Model is waiving the current statutory disincentive for Part D sponsors to design PDPs that offer supplemental benefits to lower beneficiary cost sharing in the coverage gap. Beginning January 1, 2021, CMS is testing this model for insulin, and participating pharmaceutical manufacturers will continue to pay a 70% discount in the coverage gap for their insulins on the full negotiated price, before any plan supplemental benefits.14

According to CMS, this model is a prime example of removing a statutory or regulatory barrier to improve how the market works. Based on the number of applications for participation, there appears to be broad interest from both pharmaceutical manufacturers and Part D sponsors to offer better benefits to patients.

A spokesperson for CMS stated that there are a number of benefits for those who participate in this model, accomplished by better aligning incentives and fixing a current statutorily set programmatic disincentive. First, beneficiaries who use insulin and are in a Part D Senior Savings Model–participating plan will pay less for their insulin prescriptions. Second, and potentially most importantly, beneficiaries who use insulin should have greater blood sugar control and, over time, experience fewer complications from uncontrolled diabetes. Over 1.3 million beneficiaries who use 1 or more insulin drugs, and do not qualify for Extra Help (discussed next), are eligible to benefit from the Part D Senior Savings Model. These beneficiaries may either already be enrolled in a Part D Senior Savings Model–participating enhanced standalone PDP or Medicare Advantage plan that offers prescription drug coverage, or they can enroll in one during open enrollment from October 15 through December 7. Their coverage would begin on January 1, 2021.

Low-Income Subsidy for Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage (Extra Help)

CMS and the Social Security Administration work together to provide Medicare Part D premium and cost-sharing subsidies to help with PDP costs for low-income beneficiaries. The Part D Low-Income Subsidy (Extra Help) program is available to Medicare beneficiaries with limited income and resources and provides an estimated $5000 per year in assistance with Medicare PDP costs.20 These financial subsidies help with the costs of monthly Part D premiums, annual deductibles, and prescription co-payments. Beneficiaries receiving Extra Help also have access to Special Enrollment Periods every 3 months (January-March, April-June, and July-September) outside of the annual enrollment period (October-December) to join or switch Medicare Part D plans and are exempt from the Part D late enrollment penalty.21 These protections may be particularly helpful for patients with diabetes who start taking, or switch to, a medication that is not on their current plan’s formulary outside of the annual Open Enrollment Period.

Approximately 13 million (3 in 10) individuals enrolled in Part D received assistance with premiums and cost sharing through the Extra Help program in 2019.9 Medicare beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, receive Supplemental Security Income, or qualify for Medicare Savings Programs (eg, Qualified Medicare Beneficiary, Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary, and Qualifying Individual) qualify for full subsidies and are automatically enrolled in the Extra Help program; however, they will still need to choose a PDP.22 Individuals who do not meet these criteria, but have resources that are limited to $14,610 for an individual or $29,160 for a married couple living together in 2020, may qualify for Extra Help after applying through the Social Security Administration. The annual income limits for Extra Help are $19,140 for an individual or $25,860 for a married couple living together, although beneficiaries with higher incomes may be eligible for Extra Help in certain circumstances, such as when the beneficiary or spouse supports other family members living in the household, has earnings from work, or lives in Alaska or Hawaii.20 Cash payments that do not count toward these income limits include those from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, housing or home energy assistance, medical treatments and drugs, disaster assistance, payments from earned income tax credits, assistance from others to pay household expenses, victim compensation payments, and scholarships and education grants.20

An analysis of the Access to Care files from the 2005 to 2007 Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys showed that only 40.6% of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries who were eligible for Extra Help were enrolled in the program and 18.1% of beneficiaries eligible for Extra Help had no drug coverage.23 Multivariate analysis results showed that enrollees with a Medicare Advantage plan were less likely to have Extra Help coverage, and beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions were more likely to enroll in the Extra Help program.23 Although the KFF estimates that approximately 13 million Part D enrollees receive premium and cost-sharing assistance through the Extra Help program, this population represents only 28% of all Part D enrollees in 2019, a sharp decline from the 42% who were enrolled in 2006.9

Results of an analysis of CMS 2006 to 2019 plan files by the KFF also showed a decrease in the proportion of Extra Help enrollees in standalone PDPs (from 87% in 2006 to 57% in 2019), but an increase in the proportion of Extra Help beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage PDPs (from 13% in 2006 to 39% in 2019).9 Medicare Advantage plans provide an all-inclusive plan that includes Medicare Part A, Part B, and usually Part D, and may offer additional benefits not provided by original Medicare, such as vision, hearing, and dental services, with lower out-of-pocket costs.24 However, beneficiaries are typically limited to the doctors in the plan’s network and may need to get a referral to see a specialist, whereas beneficiaries with original Medicare can go to any doctor or hospital that takes Medicare and do not need a referral for a specialist.24

Furthermore, the proportion of Part D enrollees who received low-income subsidies has decreased from 42% in 2006 to 28% in 2019, and the rate of increase in Extra Help enrollment (2.4% compound annual growth rate) has lagged behind the growth rate of enrollment in Part D overall (5.7%) and total Medicare (3.6%).9 This lack of utilization prompted the National Council on Aging to publish a call to action in 2017 to encourage the establishment of permanent federal funding for community-based organizations to facilitate the outreach, assistance, and enrollment of low-income Medicare beneficiaries who are already eligible under current regulations.25

By enrolling in a benchmark PDP, beneficiaries are generally able to obtain coverage without paying a premium. However, KFF data showed that 1 million Extra Help beneficiaries (8% of all Extra Help beneficiaries) paid a premium for Part D coverage in 2019. This number included 700,000 enrollees who were not in a benchmark PDP and 300,000 enrollees in a Medicare Advantage PDP that charged a premium. The average premium payment for Extra Help beneficiaries was $24 per month—a 7% decrease from 2018, but 2.6 times greater than the amount paid in 2006.9

Patient Assistance Resources

Selecting the most cost-effective plan can be challenging for older adults with diabetes, and because they often require multiple health care providers and medications for management, identifying a plan with optimal coverage can be even more difficult. Although navigating the process of enrolling in Medicare and choosing the correct plan can be complex, several organizations exist that can assist older adult patients in this process (see Patient Resources for Older Adults with Diabetes).

One such organization is the Medicare Rights Center, a national nonprofit based in New York, with a satellite office in Washington, DC. The organization provides client services—such as a national help line that fields questions about health care coverage, affordability, access to care, and more—as well as occasional direct representation on appeals and assistance with applications to the Medicare savings programs.

“We speak to a number of people who call [our help line] because they are having trouble affording the premiums, cost sharing, or their prescription drug costs, and they do not know about programs that could help them. They do not know about the Medicare saving’s program; they do not know about the LIS program for Part D; or they do not know about state assistance programs.”Casey Schwarz, JD

Senior Counsel

Education & Federal Policy

Medicare Rights Center

Furthermore, the Center provides educational materials for patients, providers, beneficiaries, social workers, and other professionals who work with Medicare. The organization also has a policy team who work in various states and Washington, DC, to bring the concerns and questions captured through the help line to policy makers and decision makers with the aim to advance changes that would improve access to health care for Medicare beneficiaries and also to work to protect against changes that would be detrimental to this population.

Among the biggest unmet needs gleaned from the helpline is education about Medicare, according to Casey Schwarz, JD, senior counsel, Education & Federal Policy at the Medicare Rights Center. “The biggest and first educational need is that people need to understand when they need to enroll in Medicare,” according to Schwarz [Medicare Rights Center]. “The second unmet educational need is around Medicare choice and whether a Medigap or a Medicare Advantage or Part D plan is the right one for that person. This is a burdensome decision-making process, and resources like our helpline are there to provide assistance. The third unmet need [is affordability]. The information is there for those who know to look for it, but providers [can help] be there for those patients who do not know how to ask about these things. [Some patients] are not necessarily at a point that the financial strain is so much that they are actively seeking out assistance, but rather [they are] just bearing up under it. Because providers have [more] contact with these patients, they are able to capture more people who could benefit from the[se] programs, even if they are not aware of them.”

“Health care providers on the front lines can do their best to be as proactive as possible to ensure patients start looking for some of the professional resources [to help with affordability and navigating Medicare].”Casey Schwarz, JD

Senior Counsel

Education & Federal Policy

Medicare Rights Center

In addition to the Medicare Rights Center, the Center for Medicare Advocacy (CMA) also works to aid patients who may have challenges accessing care or affording their medications. CMA is a nonpartisan, nonprofit consumer advocacy organization dedicated to Medicare beneficiary access to quality affordable Medicare services and health care. They provide direct representation to Medicare beneficiaries, and also engage in both policy advocacy and litigation on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries, which can impact class action litigation.

JDRF also provides education for patients to build awareness of available programs. “[At JDRF] we created a web-based insurance guide that includes information to help patients understand how to pick their plan and then how to use it to their benefit. We [also include] sources of assistance for the insulin and the devices, such as manufacturers’ coupon programs and patient assistance programs,” Hutton said.

In addition to online education resources, patients also may benefit from being connected with a diabetes care and education specialist who focuses on not only ensuring patients’ health needs are met and maintained, but also helping patients navigate technology, identifying the right resources, and supporting the efforts of population health needs.

“If you give people the tools they need to keep their disease stable, then they will avoid acute events and long-term complications that are very expensive.”Campbell Hutton

Vice President

Regulatory and Health Policy

JDRF

Particularly with the advent of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, diabetes care and education specialists can help connect older adult patients with providers through telehealth. According to Diana Isaacs, PharmD, BCPS, BC-ADM, BCACP, CDCES, clinical pharmacist specialist in the Cleveland Clinic Diabetes Center and Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists (ADCES) 2020 Diabetes Educator of the Year, “We have an initiative where we are proactively scheduling patients with diabetes [who are] over the age of 60 with endocrinology and diabetes care and education specialists to ensure we are checking in on them and assessing their needs. With the ease of telehealth, it is not as much of a barrier to those who are older [as it once was]. The majority of patients have smart phones. Older patients can be at higher risk of hypoglycemia and they go off and on more medications, so there can be the risk of drug interactions. Addressing those aspects and performing medication reviews [can reduce these issues], and checking in is important, particularly now [with COVID-19], as patients are feeling more isolated.”

According to Isaacs [ADCES], providers can take a proactive role in ensuring patients are connected with a diabetes care and education specialist. For providers who may not already have recommendations, there are a few organizations that can help. “[If a] provider does not work with someone or does not have an established relationship with a health care team, the American Diabetes Association and the ADCES are the 2 organizations that have accredited diabetes education programs [and the ability to grant accreditation]. Their websites [provide a tool] where an individual can input their zip code and all the accredited programs that are within a certain mile radius will pop up. There are also contact numbers to call and schedule an appointment.” These services are reimbursable through Medicare as diabetes self-management, education, and support.

ADCES also provides tools to help navigate insurance. “[There are] a lot of different programs, but it can be really challenging to navigate [them].” Isaacs [ADCES] said. “[ADCES] has toolkits available on the website that can be used when working with a patient to determine what is going to work best for their unique situation, because you have to know which programs will work with Medicare and then which programs won’t.”

“It is important to have a discussion [with the patient] during open enrollment, [because] it may be beneficial [for them] to consider a different plan that’s going to offer better coverage for the medications that they really need.”Diana Isaacs, PharmD, BCPS, BC-ADM, BCACP, CDCES

Clinical Pharmacist Specialist

Cleveland Clinic Diabetes Center

Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists

2020 Diabetes Educator of the Year

The Medicare website also provides general tips for selecting a Medicare drug coverage plan based on factors such as the types of drugs the patient takes, need for extra protection from high prescription drug costs in the coverage gap, desire for predictable drug expenses throughout the year, and the importance of restrictions on which doctors, hospitals, and other care providers patients can use.26 According to CMS, providers and beneficiaries should look for information from CMS before and during open enrollment, or they can contact 1-800-MEDICARE and go onto the Medicare Plan Finder (medicare.gov/plan-compare/) to find a plan that best suits their needs. Providers can also help their patients by directing them to these resources or helping them find a plan. CMS is actively making updates to the Medicare Plan Finder on their website so that beneficiaries will be able to easily and quickly see plans in their area that are participating in the Part D Senior Savings Model.

“We are starting to see major gains, such as a cap to $35 insulin for Medicare patients. [This] is not going to help everyone; but, I think it is coming to light that [insulin affordability] is a major problem. No one should feel like they are alone and struggling with the cost of their medications. There are a lot of different programs out there, and [it just takes] talking to your team or to a diabetes care and education specialist to determine what is going to work best for the individual patient.”Diana Isaacs, PharmD, BCPS, BC-ADM, BCACP, CDCES

Clinical Pharmacist Specialist

Cleveland Clinic Diabetes Center

Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists

2020 Diabetes Educator of the Year

For beneficiaries who do not qualify for the programs discussed here, patient assistance programs are available through individual manufacturers of diabetes medications and devices, as well as through programs such as the Affordable Insulin Project and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Prescription Savings Directory. State pharmaceutical assistance programs are also available in certain states and assist low-income seniors in paying for prescription drugs. Eligibility for these assistance programs varies among states, with some only offered to individuals enrolled in Medicare who do not qualify for the Part D Extra Help, and others only offered to individuals with specific chronic conditions (see Patient Resources for Older Adults with Diabetes for a list of available resources).

Community pharmacies may also have low-cost generic lists or programs that can be provided to patients and health care providers to assist with the selection of less expensive alternatives—if safe and appropriate for the patient—and purchasing store-brand generics for glucose meters, syringes, and test strips can also help lower costs. For patients who may need additional help determining if they qualify, state-level legal aid, insurance counseling, and assistance programs can be additional resources. “[All] legal aid programs in the United States will have someone who works on Medicaid cases who can help discuss [available] resources,” according to Cassandra Edner, JD, LSNV. “State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP) counselors are available to specifically help patients navigate Medicare plans. Legal aid may be available to help more with specific issues, such as what a patient needs to do to qualify for Medicaid. Or, if a patient received a denial, they can help with questions about these Medicaid programs and the Medicare [Savings] programs.”

Overall, addressing financial burdens for older adult patients with diabetes using strategies based on the patient’s needs for treatment and eligibility for financial assistance programs will help improve adherence and reduce the risk for long-term complications.

Roadmap: Counseling Points for Providers on Helping Patients with Medicare Lower the Out-of-Pocket Costs of Their Diabetes MedicationsPatient Resources for Older Adults With DiabetesChecklist: Eligibility for Medication Assistance Programs—EnglishChecklist: Eligibility for Medication Assistance Programs—EspañolReferences

1. Fong JH. Out-of-pocket health spending among Medicare beneficiaries: Which chronic diseases are most costly?. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222539. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222539

2. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S.). Healthy aging: helping people to live long and productive lives and enjoy a good quality of life. CDC. May 11, 2011. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/22022

3. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S.). The state of aging & health in America 2013. CDC. 2013. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://cdc.gov/aging/pdf/state-aging-health-in-america-2013.pdf

4. Chronic conditions charts: 2017. CMS. Updated April 5, 2019. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/Chartbook_Charts

5. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US In 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917-928. doi:10.2337/dci18-0007

6. National diabetes statistics report 2020. CDC. Updated February 14, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html

7. 2020 annual report of the boards of trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. CMS. 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020. http://cms.gov/files/document/2020-medicare-trusteesreport.pdf

8. How to get prescription drug coverage. CMS. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/howto-get-prescription-drug-coverage

9. Cubanski J, Damico A, Neuman T. 10 things to know about Medicare Part D coverage and costs in 2019. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 4, 2019. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-aboutmedicare-part-d-coverage-and-costs-in-2019/

10. Yearly deductible for drug plans. CMS. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/yearly-deductible-fordrug-plans

11. Copayment/coinsurance in drug plans. CMS. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/copaymentcoinsurancein-drug-plans

12. Costs in the coverage gap. CMS. Accessed July 30, 2020.https://medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-formedicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap

13. Phases of Part D coverage. Medicare Interactive. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.medicareinteractive.org/getanswers/medicare-prescription-drug-coverage-part-d/medicare-part-d-costs/phases-of-part-d-coverage

14. Part D senior savings model. CMS. March 11, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/part-d-senior-savings-model

15. Eaddy MT, Cook CL, O’Day K, Burch SP, Cantrell CR. How patient cost-sharing trends affect adherence and outcomes: a literature review. PT. 2012;37(1):45-55.

16. Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, et al. Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA. 2001;285(4):421-429. doi:10.1001/jama.285.4.421

17. Thornton Snider J, Seabury S, Lopez J, McKenzie S, Goldman DP. Impact of type 2 diabetes medication cost sharing on patient outcomes and health plan costs. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6):433-440.

18. Cubanski J, Damico A. Medicare Part D: a first look at prescription drug plans in 2020. Kaiser Family Foundation. November 14, 2019. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-part-d-a-first-look-atprescription-drug-plans-in-2020/

19. Coleman K. Implementing supplemental benefits for chronically ill enrollees. CMS. April 24, 2019. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/HealthPlansGenInfo/Downloads/Supplemental_Benefits_Chronically_Ill_HPMS_042419.pdf

20. Understanding the extra help with your Medicare Prescription Drug Plan. Social Security Administration. March 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-10508.pdf

21. Special circumstances (special enrollment periods). CMS. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/sign-upchange-plans/when-can-i-join-a-health-or-drug-plan/specialcircumstances-special-enrollment-periods

22. Guidance to states on the Low-Income Subsidy. CMS. February 2009. Accessed July 30, 2020.https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-and-Enrollment/LowIncSubMedicarePresCov/Downloads/StateLISGuidance021009.pdf

23. Shoemaker JS, Davidoff AJ, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, Onukwugha E, Powers C. Eligibility and take-up of the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy. Inquiry. 2012;49(3):214-230. doi:10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.03.04

24. Understanding Medicare Advantage plans. CMS September 2019. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/12026-Understanding-Medicare-Advantage-Plans.pdf

25. National Council on Aging. Improving Medicare low-income beneficiary enrollment. April 2017. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://d2mkcg26uvg1cz.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/IB17-Low-Income-Outreach-and-Enrollment-April.pdf

26. 6 tips for choosing Medicare drug coverage. CMS. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coveragepart-d/how-to-get-prescription-drug-coverage/6-tips-forchoosing-medicare-drug-coverage