- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

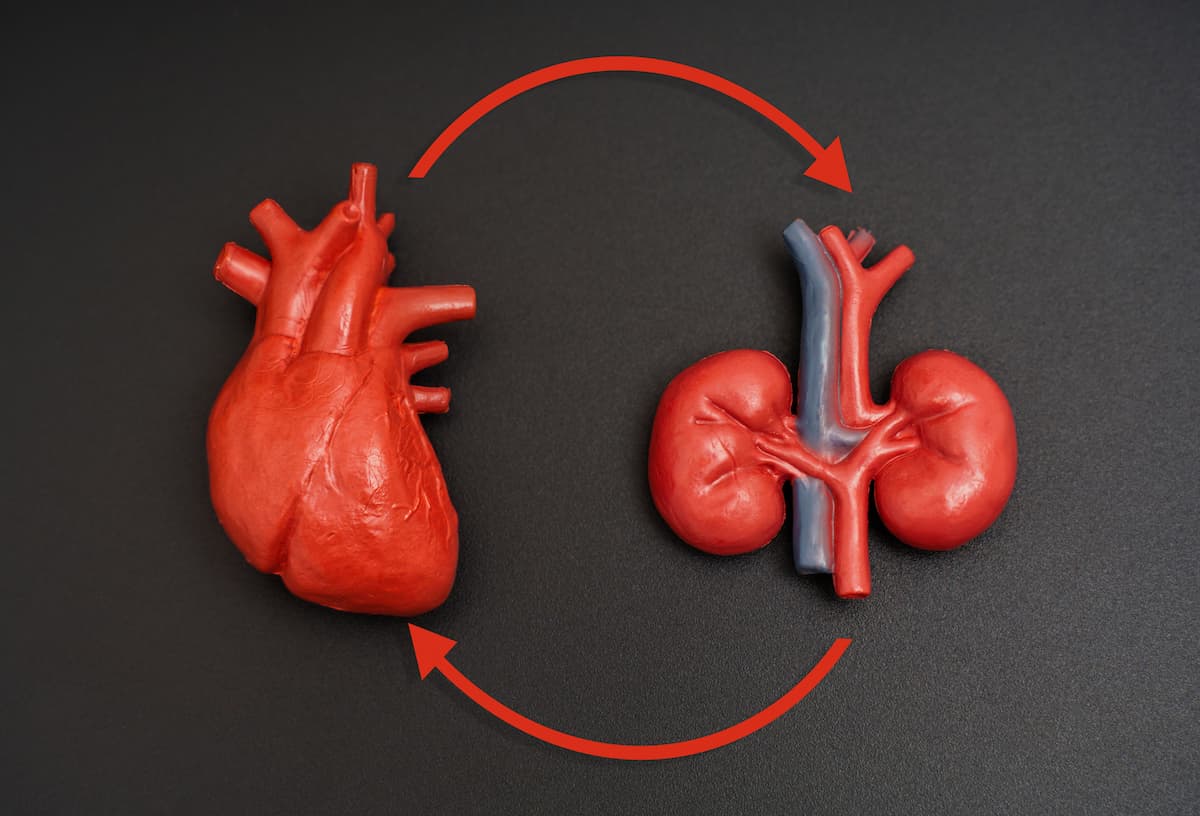

Lipid Management Remains Central to Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in CKD

Dyslipidemia significantly impacts cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease, necessitating tailored lipid management strategies for optimal patient outcomes.

Fatty acid metabolism may not be the first issue clinicians associate with chronic kidney disease (CKD), but a growing body of evidence suggests that disordered lipid profiles play a central role in the cardiovascular risk that shapes long-term outcomes for this population.1

A recent narrative review, published in the Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, synthesized decades of clinical trial data and international guideline recommendations to clarify how dyslipidemia should be assessed and treated across the spectrum of CKD severity.

These findings reinforced statins, with or without ezetimibe, as the cornerstone of cardiovascular risk reduction in most people living with CKD who are not on dialysis. | Image credit: Katie Chizhevskaya - stock.adobe.com

People living with CKD face a markedly higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than the general population, and this risk rises as kidney function declines.2 Dyslipidemia is common in CKD, but its presentation differs from the classic pattern seen in individuals without kidney disease. Rather than isolated elevations in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), CKD is typically associated with elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and qualitative changes in LDL particles, including a higher proportion of small, dense LDL.3 These differences help explain why traditional lipid targets and treatment strategies have produced inconsistent cardiovascular benefits in advanced CKD.1

The authors conducted the review to address persistent uncertainty about lipid-lowering therapy in CKD, particularly in people receiving dialysis or living with kidney transplants. They summarized randomized controlled trials evaluating statins, ezetimibe, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, fibrates, and omega-3 fatty acids, and compared recommendations from major organizations, including Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology.

Across CKD stages 1 through 5 in individuals not receiving dialysis, the evidence consistently supported statin-based therapy for cardiovascular risk reduction. The landmark SHARP trial (NCT00125593) enrolled 9270 adults with stage III to V CKD, including 6247 not on dialysis, and found that simvastatin plus ezetimibe reduced major atherosclerotic events by 17% compared with placebo over a median follow-up of 4.9 years. Participants had a mean estimated glomerular filtration rate of approximately 27 mL/min/1.73 m², and the benefits were achieved without excess risk of serious adverse events.

Meta-analyses reinforced these findings, showing relative risk reductions of roughly 25% to 30% for major cardiovascular events among people with non–dialysis-dependent CKD treated with statins. Importantly, these benefits did not appear to extend to slowing progression to kidney failure, underscoring that lipid-lowering therapy should be viewed primarily as a cardiovascular intervention rather than a renoprotective one.

In contrast, large trials in people receiving maintenance dialysis yielded neutral results. The 4D and AURORA trials, which evaluated atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, respectively, demonstrated substantial LDL-C reductions but no significant decreases in composite cardiovascular outcomes. The review attributed these findings to the distinct cardiovascular pathophysiology of advanced CKD, where arrhythmia, vascular calcification, and heart failure may play larger roles than atherosclerosis. As a result, KDIGO and other guidelines advised against initiating statins in dialysis-dependent CKD, while recommending continuation in people who were already receiving therapy before dialysis initiation.

Kidney transplant recipients represented another high-risk subgroup. The ALERT trial suggested that fluvastatin reduced cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial infarction, particularly with longer follow-up, supporting guideline recommendations to use statins cautiously in this population while monitoring for drug-drug interactions with immunosuppressive therapies.

Newer lipid-lowering agents also received attention. PCSK9 inhibitors demonstrated consistent LDL-C reductions and cardiovascular benefit across mild to moderate CKD in large outcome trials, although people with advanced CKD and transplant recipients were underrepresented. The authors noted that these agents “may be considered in selected individuals who require additional LDL-C lowering despite maximally tolerated statin therapy,” while acknowledging the limited data in later CKD stages.

Triglyceride-lowering therapies, including fibrates and omega-3 fatty acids, showed less consistent evidence. Safety concerns and sparse CKD-specific trial data led most guidelines to discourage routine fibrate use, except in cases of severe hypertriglyceridemia to prevent pancreatitis. High-dose icosapent ethyl reduced cardiovascular events in a broad population that included people with moderate CKD, but conflicting trial designs and subgroup data limited firm conclusions for routine CKD care.

The review had several limitations. As a narrative synthesis, it relied on previously published trials that often excluded people with advanced CKD, multiple comorbidities, or older age. Heterogeneity in study populations and end points limited direct comparisons across therapies, and evidence for newer agents in dialysis-dependent CKD and transplant recipients remained sparse.

Still, the authors emphasized that treatment decisions should be individualized. “The association between LDL-C and cardiovascular risk is attenuated as kidney function declines,” they wrote, underscoring the need for risk-based rather than target-based strategies in many patients with CKD.

The findings reinforced statins, with or without ezetimibe, as the cornerstone of cardiovascular risk reduction in most people living with CKD who are not on dialysis. At the same time, they highlighted critical evidence gaps in advanced disease stages and the importance of tailoring lipid management to kidney function, comorbid conditions, and patient preferences rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach.

References

1. Kim JY, Chung SM, Kim NH. Managing dyslipidemia in chronic kidney disease: a comprehensive overview of evidence and recommendations. Korean J Intern Med. 2025;40(6):876-889. doi:10.3904/kjim.2025.099

2. Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2073-2081. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5

3. Iseki K, Yamazato M, Tozawa M, Takishita S. Hypocholesterolemia is a significant predictor of death in a cohort of chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;61(5):1887-1893. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00324.x

Personalized Care Key as Tirzepatide Use Expands Rapidly

April 15th 2025Using commercial insurance claims data and the US launch of tirzepatide as their dividing point, John Ostrominski, MD, Harvard Medical School, and his team studied trends in the use of both glucose-lowering and weight-lowering medications, comparing outcomes between adults with and without type 2 diabetes.

Listen