- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

From Evidence to Implementation: Clarifications Around the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

AJMC® Peer Exchange™ provides a multi-stakeholder perspective on important issues facing managed care professionals in the evolving health care landscape.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral therapy is effective for reducing transmission of HIV in individuals at high risk for infection. In 2019, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that clinicians offer PrEP with effective antiretroviral therapy to individuals who are at high risk of HIV acquisition, due to a high certainty that the net benefit would be substantial (grade A).1 Section 2713 of the Public Health Service (PHS) Act, as added by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), requires no-cost coverage of evidence-based items or services with a USPSTF “A” or “B” rating for plan years that begin 1 year after issuance of the recommendation or guideline.2,3 The US Department of Health and Human Services determined that coverage of HIV PrEP medications and related laboratory tests and clinic visits must be provided by most commercial insurers and most Medicaid programs with no out-of-pocket costs for patients.3

Although this legislation aims to reduce the cost barrier for HIV PrEP, ongoing education of patients, providers, and payers is needed to improve uptake in populations with high rates of infection, according to a panel of experts who participated in “From Evidence to Implementation: Clarifications Around the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis,” a recent AJMC® Peer Exchange™. The panel was moderated by Ryan Haumschild, PharmD, MS, MBA, director of pharmacy services at Emory Healthcare and Winship Cancer Institute in Atlanta, Georgia, and included perspectives from policymakers, insurance payers, and health care providers. The patient journey, barriers to access, intentions of the ACA Part 47 guidance around HIV PrEP, and strategies to improve access to PrEP among eligible patients were all topics of discussion. This article is a summary of stakeholder insights from the Peer Exchange™.

Benefits of PrEP and Barriers to Uptake

According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), by the end of 2019, approximately 1.2 million individuals were living with HIV in the United States, with an estimated 36,801 individuals in the United States and dependent areas receiving a diagnosis of HIV that same year (2019).4 Although the annual number of new US diagnoses decreased by 9% from 2015 to 2019, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino populations had disproportionately high rates of diagnosis, accounting for 42% and 29% of new diagnoses, respectively, in 2019.4 Young individuals (aged 13-24 years) also were disproportionately affected, accounting for 21% of new diagnoses. The majority (83%) of new diagnoses in this age group were among gay and bisexual men, 50% of whom identified as Black/African American individuals.4 These data highlight the importance of focusing interventions for HIV prevention on populations with disproportionately high prevalence of and risk for HIV infection.3

The use of antiretroviral drugs for PrEP is an effective strategy for HIV prevention in individuals who are at high risk of infection.5,6 The use of oral F/TDF (Truvada, Gilead)—a combination of emtricitabine with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)—was compared with placebo in high-risk, HIV-seronegative individuals in 2 trials.5,6 Results from the Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative trial (NCT00458393) indicated that the use of oral F/TDF was associated with a 44% relative reduction in HIV acquisition among transgender women and men who have sex with men (95% CI, 15%-63%; P < .005).5 In the Partners PrEP trial (NCT00557245), use of oral F/TDF was associated with a 75% relative reduction in HIV acquisition among heterosexual individuals with a serodiscordant partner (95% CI, 55%-87%; P < .001).6

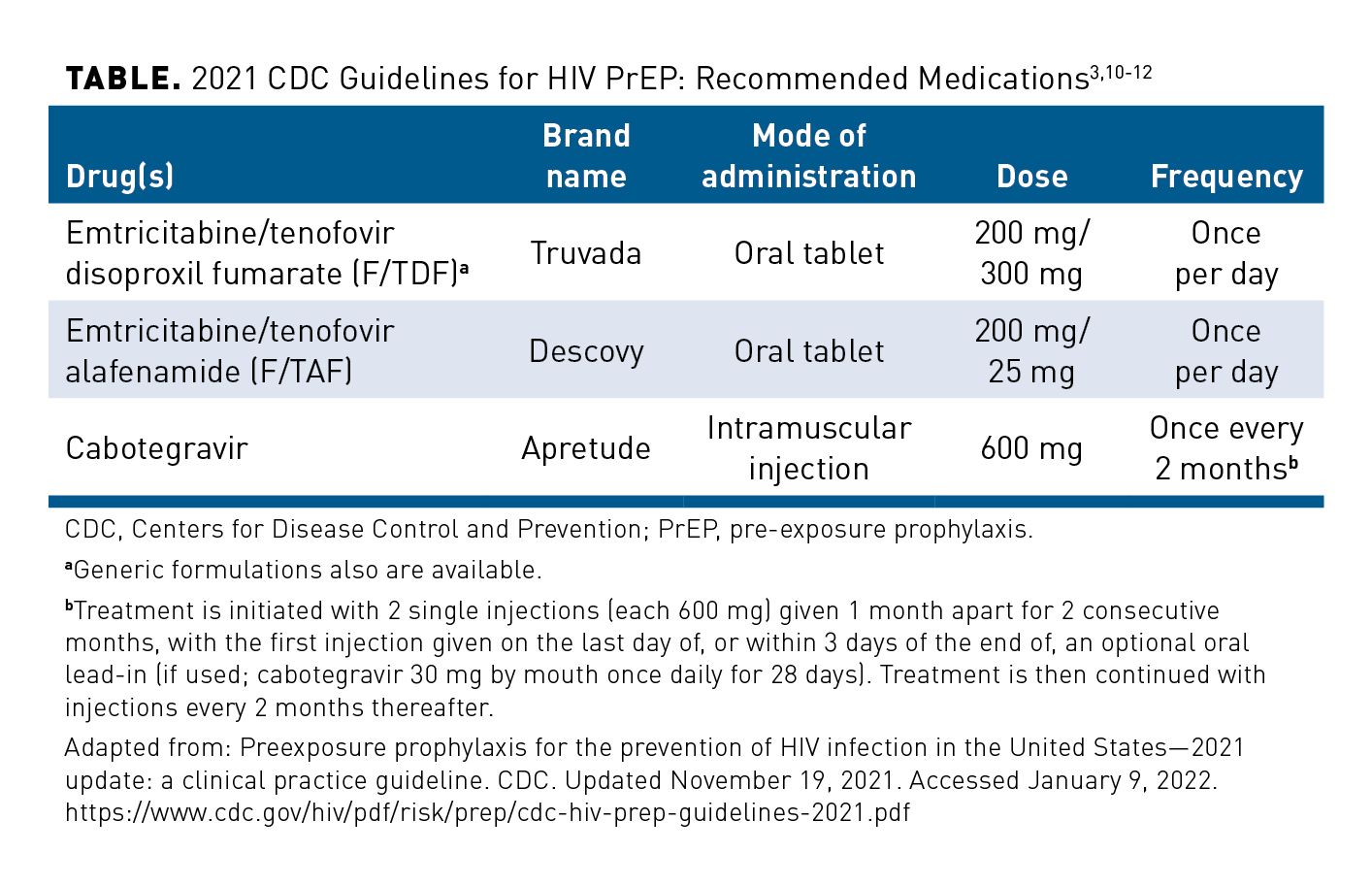

F/TDF was approved for PrEP in 2012 for individuals who are at high risk for HIV infection, and it is still the most commonly prescribed HIV PrEP medication among eligible patients.3,7 Additional treatments that have since been approved for HIV PrEP include: oral emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide (Descovy, Gilead), which was approved in 2019 (excluding individuals who have receptive vaginal sex), and injectable cabotegravir (Apretude, ViiV), which was approved in 2021.8,9 HIV PrEP medications recommended in the 2021 CDC guidelines are listed in the Table.3,10-12

Overall, data supporting the use of antiretroviral medications for HIV PrEP were strong enough for the USPSTF to issue an “A” rating recommendation.1 This means that, with high certainty, PrEP provides a substantial benefit for decreasing risk for HIV infection in high-risk individuals, such as sexually active men who have sex with men; heterosexually active men and women who have a sexual partner living with HIV, have inconsistent condom use with high-risk partners, or have had a sexually transmitted infection (STI) within the past 6 months; and individuals who share drug injection equipment.1 The USPSTF statement also includes a recommendation for counseling to address behaviors associated with risk for acquisition of STIs and HIV infection; identifies CDC-issued recommendations—abstinence, reduction in the number of sexual partners, and consistent condom use—to reduce transmission of HIV and other STIs; and recommends syringe service programs to reduce risk of HIV acquisition and transmission among individuals who inject drugs.1

The CDC updated their HIV PrEP clinical practice guidelines in 2021 to include a moderate strength recommendation based on expert opinion (IIIB) “to inform all sexually active adults and adolescents about PrEP.”3 Furthermore, in anticipation of FDA approval of cabotegravir for PrEP, and based on high quality evidence from at least 1 randomized controlled trial, the following strong (IA) recomendation was added: “PrEP with intramuscular cabotegravir injections (conditional on FDA approval) is recommended for HIV prevention in adults reporting sexual behaviors that place them at substantial ongoing risk of HIV exposure and acquisition.”3 Because evidence suggests that patients often avoid disclosing stigmatized sexual or substance use behaviors to their health care providers, particularly when providers fail to initiate conversations about these behaviors, the CDC notes in the guidelines that informing all sexually active adults about HIV PrEP may help patients to respond more openly to questions about risk assessment and to discuss PrEP with others in their social networks and families who may benefit from its use.3

After the approval of F/TDF for HIV PrEP, the estimated number of individuals who were prescribed PrEP increased from 8800 in 2012 to nearly 220,000 in 2018.3 Between 2017 and 2018, the proportion of eligible adults who received HIV PrEP increased from 12.6% to 18.1%.13 However, uptake of PrEP remained low among many populations at high risk for HIV infection.3 In 2018, although Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals had disproportionately high rates of new HIV diagnoses, only about 6% of eligible Black individuals and 10% of eligible Hispanic/Latino individuals received a prescription for oral HIV PrEP.3 Women also had low rates of uptake, accounting for 7% of those who were prescribed oral HIV PrEP in 2018.3

Stakeholder Insights

Frank J. Palella, MD, professor of medicine in the infectious diseases division of the Department of Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, said that he believes, “[HIV] PrEP is an important facet of an overall strategy of STI prevention. I think it needs to be looked at not as merely the provision of a prescription for a daily pill that can prevent HIV, but [as] one of the first steps in the establishment of a relationship to maintain an [individual’s] HIV-free and [STI-free] status.” He noted that many patients become aware of HIV PrEP through treatment counseling for STIs, public advertisements, or information acquired from peers, and they subsequently seek a provider from whom PrEP is available. Increased availability and affordability of PrEP has come from greater education and awareness, as well as the availability of a generic version of F/TDF, and the implementation of ACA guidelines that prohibit cost-sharing for PrEP, according to Ryan Bitton, PharmD, MBA, senior director of pharmacy services at the Health Plan of Nevada in Las Vegas.

The low uptake of HIV PrEP among certain subgroups (eg, Black individuals, Hispanic/Latino individuals, and women) is multifactorial. These include patients’ lack of education and awareness about personal risk for HIV infection; limited access to health care and insurance; misconceptions about associated adverse events (AEs); barriers, in the case of minors, to accessing confidential health care; stigmas related to sexual and drug-using behaviors; previous negative experiences with the health care system; and costs of PrEP and related services. According to Palella, clinicians should view HIV PrEP as a key component of the overall strategy for STI prevention, which should include counseling, provision of condoms, and a health care environment that promotes open communication between the patient and providers about PrEP and related monitoring and management. Community education and awareness campaigns should focus on Black and Latino gay and bisexual men, cisgender women (particularly Black women), and transgender individuals, said Sean E. Bland, JD, senior associate with the Infectious Diseases Initiative at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law in Washington, DC. Bland added that these campaigns also should emphasize the safety and efficacy of HIV PrEP, address and dispel misconceptions about its value for HIV prevention across all appropriate populations, and focus on its place in reducing anxiety around risky sexual behavior.

A lack of discussion between providers and patients about sexual health also is a barrier to access, and a behavioral risk assessment may not be adequate for determining candidacy for HIV PrEP. Bland emphasized the importance of providers offering a safe environment for individuals to discuss sexual and drug-using behaviors, one in which feelings of stigma can be reduced. “Risk assessment doesn’t always take into account some of the structural and environmental factors that impact vulnerability to HIV [acquisition],” Bland added. “It’s important to address stigma and to address bias and discrimination from providers and others related not just to sex and HIV, but also to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, income, and other issues,” he said. Bland also emphasized that even among those with insurance, the cost of HIV PrEP and related services may prevent individuals from seeking health care. He added that lack of access or disrupted access to insurance also may be a barrier. Moving forward, payers could improve uptake of HIV PrEP by advertising its availability as a free preventive service, thereby improving their partnership with the health care community by increasing transparency around coverage and ensuring access.

Affordable Care Act Implementation Part 47: FAQs

With the June 11, 2019, release of the USPSTF recommendation that clinicians offer PrEP and related services to individuals at high risk for HIV infection, plans and issuers are required to cover PrEP without cost sharing for plan (or policy) years beginning on or after June 30, 2020.2 To inform relevant parties about the intended law and benefit, the US Departments of Labor and of Health and Human Services, along with the US Treasury, jointly prepared responses to “FAQs about ACA Implementation Part 47” in July 2021, with the goal of clarifying the recommendations.2 Because other antiretroviral drugs or drug regimens have been, or are being, investigated in clinical trials, at the time of this publication, an update of the USPSTF HIV PrEP recommendations is in progress. These recommendations and the CDC guidelines will continue to be updated based on approval of HIV PrEP drugs in new populations and with new agents and formulations.1,3

FAQ 1: Are plans and issuers required to provide coverage without cost sharing for items or services that the USPSTF recommends should be received by a participant, beneficiary, or enrollee prior to being prescribed antiretroviral medication as part of the determination of whether such medication is appropriate for the individual and for ongoing follow-up and monitoring?2

No-cost coverage is required for HIV PrEP-related services recommended by the USPSTF Final Recommendation Statement, which states that PrEP is a comprehensive intervention consisting of both antiretroviral medication and support services (eg, medication self-management and adherence counseling, strategies for risk reduction, and mental health counseling).2 Baseline monitoring includes a medical history; HIV testing (to exclude individuals with acute or chronic HIV infection); and testing for kidney function, hepatitis B and C viral infections, other STIs, and pregnancy status (in individuals of childbearing potential) at the time of or immediately prior to initiation of PrEP.2 Follow-up and management include repeated HIV testing every 3 months (for patients taking oral PrEP) or every 2 months (for individuals receiving cabotegravir injections), as well as adherence support.3 Such support involves establishment of trust and open communication with patients, patient education, reminder systems for taking medication, and identification and management of related AEs.2

FAQ 2: May a plan or issuer use reasonable medical management techniques to restrict the frequency of benefits for services specified in the USPSTF recommendation for PrEP, such as HIV and STI screening, in a manner specified under other existing USPSTF recommendations, or otherwise?2

Although section 2713 of the PHS Act allows plans or issuers to use reasonable medical management techniques to establish coverage limitations, insurance plans or issuers cannot use these to restrict the frequency of benefits for HIV PrEP-related services that are specified in the USPSTF recommendation. Restricting the number of times that an eligible individual starts HIV PrEP “would not be reasonable.”2

FAQ 3: When may a plan or issuer use reasonable medical management techniques with respect to coverage of PrEP?2

Plans and issuers can use reasonable medical management techniques to encourage individuals to use particular items and services if the frequency, method, treatment, or setting is not specified in the USPSTF recommendation (eg, coverage of a generic version without cost sharing and imposition of cost sharing on the equivalent branded version).2 However, the plan or issuer needs to have an exceptions process that is accessible, transparent, and expedient, and that does not place an undue burden on the individual, provider, or other authorized representative.2

Stakeholder Insights

According to Bitton, the primary intent of the new legislation is to offer therapies that help patients live healthier lives. The stakeholders predicted that this grade “A” rating by the USPSTF for HIV PrEP and related services—and consequent implications for coverage by payers—will help reduce barriers related to costs of the drug, laboratory testing, and follow-up office visits. He asked, “How do we balance the intent of the legislation and regulation with [our role] as a payer? How can we make access to these critical therapies and critical services available in a cost-appropriate way, and what [can] payers do to help manage [these associated costs]?”

Much work remains to be done to ensure that the legislation is fully implemented, according to Carl Schmid, MBA, executive director at the HIV and Hepatitis Policy Institute in Washington, DC. Because these ACA regulations do not apply to patients on Medicare, and some employer plans may choose not to follow them, he noted that patients may have difficulties with identifying whether their plan is required to provide HIV PrEP and related services at no cost. Palella added that, in his experience, often there are discrepancies between the most appropriate preventive therapy identified by the prescribing provider and the least costly option identified by the payer, and the provider may need to justify their selection to the payer. Furthermore, Schmid said that many patients report receiving bills for ancillary services related to HIV PrEP, such as laboratory tests, that should be covered without cost sharing. It is important for payers to remain diligent in ensuring that guidelines are followed and that ease of access for patients is not compromised.

Schmid added that the CDC guidelines on the frequency of which follow-up tests are needed while patients are taking HIV PrEP often change; therefore, he recommended that payers and providers refer to the most recent version of the recommendations.

Palella noted that the periodicity of follow-up also has a substantial effect on patients' overall sexual health, with more frequent monitoring being associated with a reduction in STIs such as gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia. The STI screening frequency recommended by the CDC for all sexually active individuals on PrEP is 6 months.3 The results of 1 study that used mathematical modeling to assess the effect of this regular STI screening on the incidence of gonorrhea and chlamydia infections in men who have sex with men predicted that reducing the interval from 6 months to 3 months would increase the number of treated asymptomatic urethral and rectal cases of gonorrhea and chlamydia and result in a 50% reduction in incidence of these STIs.14 “The monitoring for PrEP is largely driven by the need for monitoring even more communicable [STIs] that often arise from sexual activities that are equally [as] likely to transmit these other [STIs] as HIV,” according to Palella. “When I speak with payers …the justification for our practices as most recently outlined by [the] CDC [is] that prevention is always going to cost less than treatment.”

In discussing the exceptions process, Bitton said that being transparent and publicly posting the prior authorization policies outlined by the ACA Part 47 FAQs removes some of the guesswork, but the complexities inherent in the current health care system introduce inconsistencies with the process that, in his experience, are frustrating to providers. Although the definition of “expedited” as it relates to prior authorization varies (eg, it may mean 24 hours with Medicaid or 72 hours with other payers), he said that within 24 hours or “as fast as possible” is a good benchmark for these purposes.

Bitton defined the medical necessity for HIV PrEP as having: supported data, an FDA indication, and a guideline recommendation for both the use of the medication in general and the use of a nonpreferred product (“Product B”) in situations in which the payer’s preferred product (“Product A”) is inappropriate. “Of course, there are situations that [don’t] fall [neatly] into a medical policy,” he said. “That’s where each individual review through the exceptions process will also determine medical necessity.”

When he makes appeals to payers on behalf of his patients, Palella said that he uses risk aversion as the guiding principle, because it is often an effective incentive. “In someone for whom I might believe that TDF is inappropriate, [such as] for persons with modest renal function or persons who already have a propensity [for] or evidence of some osteopenia, I will say it is my job as an advocate [for] and protector of this patient to not contribute to or cause a medical problem by virtue of an intervention that I am giving to prevent HIV,” he said. Palella added that communicating within the context of specific patients and their individual needs—given preexisting conditions and competing risks—tends to be more effective than making broad generalizations.

The panelists said that although the ACA Part 47 FAQs provide solid guidance, enforcement of the guidelines and the ability to process exceptions and prior authorizations efficiently remain key factors in increasing uptake of HIV PrEP. Bland added that education is needed to ensure that payers and providers know the requirements for getting HIV PrEP to eligible patients. Palella shared that the guidelines for HIV PrEP will continue to evolve as more information is gathered and as nuances in care, patient characteristics, and scenarios related to PrEP are identified. Key areas of future research will include the use of long-acting or injectable therapies for HIV PrEP and frequency of the therapies, he said.

Future Opportunities to Improve PrEP Uptake: Stakeholder Insights

The panelists noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health care disparities among individuals potentially eligible for HIV PrEP and has led to substantial decreases in testing for HIV and other STIs. The results from a study of 4 large, urban-based health care systems from 4 geographically diverse major cities within US states (Louisiana, Minnesota, Rhode Island, and Washington) found that the number of weekly HIV tests performed in outpatient settings dropped significantly from 2019 to 2020 (α < .05), with reductions ranging from 27% in Minneapolis, Minnesota (95% CI, 25%-29%), to 59% in Providence, Rhode Island (95% CI, 56%-62%).15 Not surprisingly, outpatient HIV testing was at its lowest point during each state’s stay-at-home order, ranging from a 68% reduction in testing in Minneapolis (95% CI, 65%-71%) to a 97% reduction in New Orleans, Louisiana (95% CI, 96%-98%). Testing increased after stay-at-home orders were lifted; however, across the 4 cities, rates remained 11% to 54% lower in outpatient settings (95% CI, 7%-59%) as compared with rates seen before stay-at-home orders. The investigators also found a nonsignificant trend toward an increase in HIV positivity rates in outpatient settings in most areas of the study, except New Orleans, which showed a significant decrease in positivity on outpatient HIV tests from 2019 to 2020 (1.34% to 0.72%, respectively; P = .01), but a significant increase in positivity on community HIV tests (0.65% to 1.63%; P = .008).15

The results of another study that surveyed men aged 17 to 24 years of any sexual minority group—more than half (53.5%) of whom were Black or Latino individuals—indicated that 90 of 104 participants (86.5%) who were eligible for HIV PrEP were not using it at the time of the survey.16 Further, among the 35 participants who were current or former users of HIV PrEP, 2 participants (5.7%) reported changing dosing strategies, and 5 participants (14.3%) reported discontinuing PrEP due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, of those 35 current or former users of HIV PrEP, 7 participants (20%) reported difficulties with obtaining a prescription for PrEP from their doctor, and 3 (8.6%) had trouble obtaining medication from the pharmacy.16

Bland added that the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the ability to access PrEP and other HIV prevention services has disproportionately affected vulnerable populations. The results of a survey conducted through a social media app provided responses from a global sample of adult cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with men about COVID-19’s impact on economic vulnerability, mental health, and STI prevention, testing, and treatment. Using a cross-sectional sample of data collected between April 16, 2020, and May 4, 2020, investigators found that although 65% of participants not living with HIV (n = 2247) reported having access to condoms, fewer patients reported having access to onsite HIV testing (30%), at-home HIV testing (19%), HIV PrEP (21%), or postexposure prophylaxis (17%).17 Additionally, less definite access to condoms was reported by individuals who identified as: members of racial or ethnic minority groups (P < .0001), as being from immigrant backgrounds (P = .01), or as having ever engaged in sex work (P = .048) compared with individuals who did not identify as such. Those who identified as members of racial or ethnic minority groups also reported less ability to access HIV at-home tests than did those who did not identify as such (P = .03).17

Increasing the availability of at-home HIV testing and delivering HIV PrEP services through telemedicine can help to address access barriers introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although Palella noted that in-person services are invaluable for patients and providers for creating a sense of confidence and medical intimacy, both of which are important to overcoming barriers related to stigma and social determinants of health and disparities, telehealth strategies are likely to be continued in the future due to concerns about COVID-19.

“COVID-19 has prompted the evolution of telehealth as a fundamental change in the way we do business, and [teleheath] is here to stay. The scenarios in which it can be effective, and practical, and even cost-saving are [still] being fully realized,” said Palella. “Telehealth is a boon to overall health care, including for important preventive HIV and [STI] health.”

However, Bland noted that the telehealth opportunities that were introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic may not be available for populations who do not have internet or smartphone access. Health care organizations, he said, have an important role in conducting outreach about HIV PrEP to health plans and communities and in identifying ways to adapt models of service delivery to increase access to care. He noted that initiation of and adherence to HIV PrEP can be enhanced by same-day initiation of and express visits for PrEP; utilization of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists to support its use; and recurrent auditing of health departments and regulators for state and local insurance to ensure compliance with guidelines.

Schmid added that providers and payers can broadly improve uptake of HIV PrEP through the creative use of technology (eg, advertising on dating apps) to increase awareness and reduce stigma associated with its use. Communication with policy leaders to introduce legislation on zero-cost coverage of new HIV PrEP drugs also may be helpful; however, Palella noted that peer advocacy is one of the most effective means of communicating a message to achieve the desired goals.

“Awareness, education, empowerment: these are 3 pillars of all preventive and therapeutic health care,” Palella said. “Individuals have to be aware of their own risk [and] aware of things they can do about it. [They need to] have access to [HIV PrEP] and to feel comfortable sharing information about themselves. With all the electronic capabilities, there are myriad different pathways and [shapes] that this could take.”

Schmid said that the advocacy work that he and his colleagues completed has been instrumental to the ACA legislation requiring health plans to cover ancillary services, but he declared that a system similar to the Health Resources and Services Administration's Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program is needed for people at high risk for HIV infection.18 This program funds grants to states, cities, counties, and local organizations to improve health outcomes through the reduction of HIV transmission and the provision of medical care, support services, and medications for low-income individuals living with HIV.18 Schmid did note that legislation has been introduced to establish a national program to provide HIV PrEP medications and ancillary services for uninsured and underinsured individuals and grants to support provider outreach and community education, but “there’s still a lot of work to be done.” Still, he added, “This [would establish] programs throughout the country where they’re needed to increase [uptake of HIV] PrEP.”

Closing Remarks

Routine use of HIV PrEP in individuals who are at the highest risk for HIV infection is an essential intervention for minimizing the number of new infections.13 Identifying individuals at risk for HIV infection and providing them with HIV PrEP medications, along with ongoing management and follow-up, requires a holistic approach to care and the ongoing collaboration of health care providers, third-party payers, policymakers, and individuals who understand social determinants of health, to expand access to these medications.

References

- Final recommendation statement – prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. US Preventive Services Task Force. June 11, 2019. Updated January 6, 2022. Accessed February 10, 2022. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

- FAQs about Affordable Care Act implementation part 47. Department of Labor. Updated July 19, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/aca-part-47.pdf

- Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: a clinical practice guideline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 19, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

- HIV basics: basic statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 1, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al; iPrEx Study Team. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587-2599. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011205

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al; Partners PrEP Study Team. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399-410. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1108524

- Truvada FDA approval history. Drugs. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/history/truvada.html

- FDA approves second drug to prevent HIV infection as part of ongoing efforts to end the HIV epidemic. News release. FDA. October 3, 2019. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-drug-prevent-hiv-infection-part-ongoing-efforts-end-hiv-epidemic

- FDA approves first injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention. News release. FDA. December 20, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention

- Truvada. Prescribing information. Gilead Sciences; 2020. Accessed February 11, 2022.

https://www.gilead.com/~/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/hiv/truvada/truvada_pi.pdf - Descovy. Prescribing information. Gilead Sciences; 2022. Accessed February 11, 2022.

https://www.gilead.com/~/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/hiv/descovy/descovy_pi.pdf - Apretude. Prescribing information. ViiV Healthcare; 2021. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215499s000lbl.pdf

- Harris NS, Johnson AS, Huang YLA, et al. Vital signs: status of human immunodeficiency virus testing, viral suppression, and HIV preexposure prophylaxis – United States, 2013-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(48):1117-1123. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6848e1

- Jenness SM, Weiss KM, Goodreau SM, et al. Incidence of gonorrhea and chlamydia following human immunodeficiency virus preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men: a modeling study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(5):712-718. doi:10.1093/cid/cix439

- Moitra E, Tao J, Olsen J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV testing rates across four geographically diverse urban centres in the United States: an observational study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;7:100159. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2021.100159

- Hong C, Horvath KJ, Stephenson R, et al. PrEP use and persistence among young sexual minority men 17-24 years old during the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(3):631-638. doi:10.1007/s10461-021-03423-5

- Santos GM, Ackerman B, Rao A, et al. Economic, mental health, HIV prevention and HIV treatment impacts of COVID-19 and the COVID-19 response on a global sample of cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):311-321. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-02969-0

- About the program: who was Ryan White? Health Resources and Services Administration. Updated December 2020. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program