- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Chronic Disease in the Workplace: Are We Fighting the Wrong Battle?

Whether or not employer wellness programs work remains debated, but the real question to address is whether we are even fighting the right battle.

As a strategy to improve Americans’ health status and reduce healthcare costs, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows employers to place up to 30% of total health insurance spending “at risk” for employees. Employees can keep/earn that share by participating in programs to reduce chronic disease risk factors and/or by controlling their cholesterol, blood pressure, and body mass indexes (BMI). Partly as a result of this provision, chronic disease risk factors have become a primary focus of many if not most major employers in America.

Whether these wellness programs have worked is beyond the scope of this posting, but is unresolved. In 2010 Health Affairs published an oft-cited (albeit challenged and undefended) meta-analysis finding savings with these programs. This conclusion was directionally confirmed (except for randomized control trials, which showed a negative return on investment) by a 2014 meta-analysis in a wellness trade journal. Conversely, the Incidental Economist published several pieces on the questionable finances and other concerns raised by these programs. The Bloomberg BNA Healthcare Policy Report published a concise summary of the “con” argument. A 2014 RAND study of PepsiCo found no savings.

Instead, the question to be addressed in this article is not who is right or wrong in this battle but rather whether we are fighting the right battle in the first place. Is there so much chronic disease—and is it so out of control—that self-insured employers should be spending up to $500 per employee per year plus incentives to try to avoid costly cardiometabolic events?

Most importantly, to quote a statistic that appears 200,000 times on the internet—sourced to the CDC website and traceable to a 2004 Johns Hopkins report—is it true or meaningful for employers that, to quote one example: “chronic diseases, most of which are preventable, account for 75%” of healthcare spending?1 (That statistic is a common misreading of the CDC’s original statement, which is: “75% of our healthcare spending is on people with chronic conditions.” And it includes Medicare-age patients, who are far more likely to have one. Nonetheless, it is the mantra for wellness.)

Recently—the impetus for the author checking the figure and writing this article—the CDC hiked the 75% figure to 86% of our nation’s healthcare budget being spent on people with chronic disease.

This question is easily answered using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) database: No. There may be some narrow semantic sense in which this 75% or 86% statistic is true, in that people with one or more chronic diseases are more likely to be hospitalized for anything than people without them, but that doesn’t make their chronic disease the cause of their hospitalization.

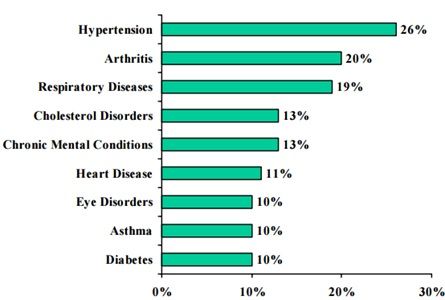

The leading chronic diseases in the Johns Hopkins report are:

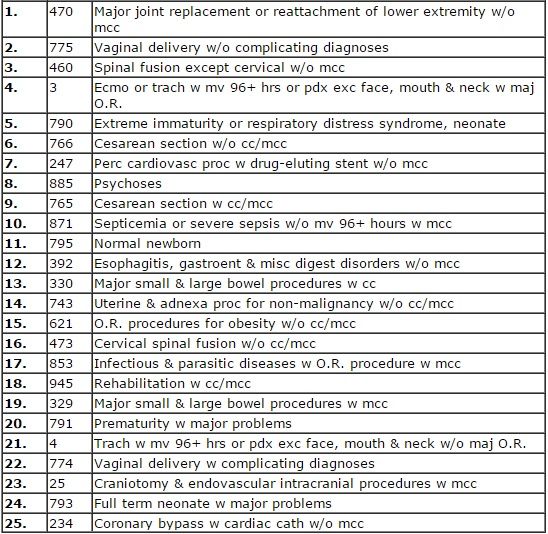

Now contrast that list to the list of the top 25 diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) in aggregate costs for the privately insured (meaning not Medicare or Medicaid) population, for the most recent year available, 2013:

Nothing on the chronic disease list appears in the top 25 DRG discharge list except mental health. While most employers have employee assistance programs to assist with mental health issues, those offerings are notable for being underutilized. (Bypasses and stents make the list, but it’s doubtful that employers are denting those rates with wellness screenings. Those are more about management of existing disease.)

One would expect—if $6 of every $7 were truly going to chronic disease in anything like a literal sense—far more representation of chronic disease on this list of top DRGs.

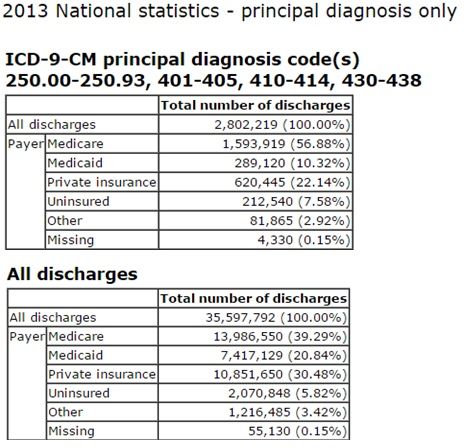

By contrast, consider the incidence rates of wellness-sensitive cardiometabolic events. Using a list of cardiometabolic, hypertension, and stroke International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), codes proposed in a 2013 Health Affairs case study of wellness, they amount to about 6% of all hospital admissions for privately insured patients or roughly 620,000 out of 10,851,000:

These events are rare enough that it costs about $1 million for an employer to predict and prevent a heart attack.

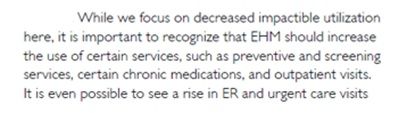

Despite the mismatch between the chronic disease list, the DRG ranking, and cardiometabolic admissions, the 75%/86% statistic has led thousands of companies to embrace wellness to avoid hospital events. They are spending $8 billion to do so, which may be more than they are spending on the admissions themselves. It is possible that there is some cost to be avoided other than hospitalizations, but the industry’s own measurement guidelines say (page 22):

The concerns of this mismatch are not solely financial: screening vendors either ignore or willfully disregard accepted clinical guidelines, thus causing potential harms to employees. (Causing harm due to overscreening and overdiagnosis does not violate the law. There are no regulations requiring wellness vendors to adhere to or even understand clinical guidelines, and malpractice laws don’t cover wellness vendors because there is no licensing requirement to be a wellness vendor.)

Time to Refocus Corporate Strategy?

Along with potential direct harms to employees, perhaps the biggest unappreciated harm of the wellness emphasis is diverting employers from list of most costly DRGs—and hence from the opportunities it reveals. (Every employer will have a somewhat different list, but most should resemble this one.) The remainder of this posting makes observations about what employers—and the government—could do based on this data.

First, orthopedics makes multiple entries. In general, the musculoskeletal category has many prevention and mitigation opportunities in the workplace. Ergonomics is one. Exercise classes, for sure. Benefits design and education to include encouraging access to lower-cost care is another.

Drilling down in orthopedics, total joint replacements have more than doubled since 2000 in the commercially insured population. Perhaps employees don’t realize that the earlier a joint is replaced, the sooner it will wear out, or that altering a gait following replacement of one joint may stress other joints. Or they may not be aware of conservative therapies. It’s also possible they would prefer conservative or alternative therapies but that their employer’s benefits design discourages their use.

Employers may find the most surprising item on the list to be spinal fusions (numbers 3 and 16). These procedures are highly controversial. Benefits design, employee education, provider profiling, and regional centers of excellence are tools that can be used to avoid inappropriate ones.

Many other items on the list of most costly DRGs are often also found on lists of overused procedures, such as stents and cesarean sections. In both cases, education about alternatives could be worthwhile.

While it is impossible to prove a negative, employers appear to be focusing on none of these items, partly explaining the composition of the list. And a simple review of the employee health trade journals shows far more emphasis on chronic disease screenings than avoiding low-value care. The authors have discovered no health risk assessment—another standard tool for wellness programs—addressing these procedures, and they believe none is in common use.

Wellness proponents might argue that wellness could reduce the incidence of many of these DRGs by helping employees lose weight. However, employer weight-loss incentives don’t seem to help employees lose weight. And in the most recent award-winning wellness program (McKesson’s), BMI actually increased. If award-winning programs can’t reduce BMI, it’s difficult to see how lesser programs could.

Bariatric surgeries (number 15) are on the list. One could argue they represent either the failure of wellness programs or their irrelevance. Either way, if employers really could help obese employees lose weight, it’s as unlikely this category would appear in the top 25 as it is that employees of a corporation with an award-winning program could gain weight.

Sepsis makes the top 10. This problem could be addressed with benefits design the way Medicare does it: pay hospitals more for each case, but don't pay them for hospital errors and infections, thus giving hospitals an incentive to reduce infection rates. The ranking of infections should steer more employers towards membership in, for example, the Leapfrog Group, which emphasizes the importance of reducing hospital errors and infections.

Should the Federal Government Change Course?

The federal government is moving in exactly the opposite direction suggested by the data: it is encouraging companies to identify and prevent chronic disease events. At the legislative level, the Senate Health, Education Labor and Pensions Committee held a hearing titled Employer Wellness Programs: Better Health Outcomes and Lower Costs. (No witnesses intending to challenge the title’s premise were invited to testify.)

In the executive branch, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is actively considering regulatory changes under the Americans with Disabilities Act that would classify participation in any wellness program, no matter how large the fines up to the ACA limits, as “voluntary,” thus depriving employees of any rights of recourse for perceived unfair treatment. Likewise, the EEOC’s proposed changes to the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act would have the practical effect of stripping employees of the right to voluntarily withhold their medical and genetic information from their employers.

The HCUP data suggests that the focus of both branches of government should be elsewhere, such as encouraging employers to help employees avoid low-value care.

As it stands today, employers are allowed to demand intrusive medical exams and even employee DNA, and if employees don’t comply, they can be fined. But they can't simply tell employees: "You need to complete this education module on the benefits and hazards of spinal fusion before being approved for one.” In addition to being unable to penalize employees for overuse or incentivize them to avoid overuse of inappropriate care, employers aren’t even allowed to know about employees’ decisions to get it.

After having just criticized wellness programs for being too prescriptive, we don’t want to be too prescriptive ourselves. Deeper dives are needed to figure out where the greatest policy and corporate opportunities are.

Nonetheless, at a very minimum, the data suggests that a pause in the headlong rush to “do wellness” is advisable while more research is undertaken to identify the best opportunities to help guide policy makers, employers, and health plans on where to focus their educational resources.

1. The “most of which are preventable” modifier that often precedes this statistic appears to have originated with Johnson & Johnson. If that were true in anything like a literal sense, many people could live forever.