- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Biosimilars for Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases – A Managed Care Perspective

ABSTRACT

Biosimilars hold the promise of substantial potential cost savings in health care with no compromise in the efficacy and safety of treatment. Despite this, their adoption in the United States has been substantially slower than might have been expected. In addition to patient and provider barriers to their widespread adoption as discussed in the second article in this supplement, additional potential barriers to their use are inherent to the current US health care system. In this article, we examine biosimilar agents from a managed care perspective and discuss some of the reasons behind their delayed adoption in the United States.

Am J Manag Care. 2022;28:S234-S239

For author information and disclosures, see end of text.

Introduction

The perceived barriers to biosimilar adoption in managed care have changed little over the last few years.1,2 According to findings of an Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Foundation survey, state regulations relating to biosimilars and interchangeability are now seen as a key issue by 40% of respondents, along with pricing and contract issues (36%), formulary placement (16%), and prescriber concerns about safety and efficacy (14%).1

Regulatory and Legal Issues

As of August 2022, the FDA had approved 37 biosimilars, 22 of which were marketed. More than 80 additional biosimilars are within the FDA’s pipeline, and over 100 are listed as being under clinical development.3 A unique aspect of the US regulatory system is the separate FDA regulatory categorization of biosimilar products and interchangeable biosimilars, which distinguishes it from the system used in European countries. (For more information, see the first article in this supplement.4) Approved biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars are listed in the searchable, online database known as the “Purple Book: licensed biological products with reference product exclusivity and biosimilarity or interchangeability evaluations.”5

The FDA’s definition of interchangeability was intended to facilitate adoption of biosimilars by explicitly permitting pharmacists to substitute an interchangeable biosimilar agent for its reference product (also called the originator biologic) without requiring prior approval from the prescriber.6 However, designation as an interchangeable biosimilar applies only to a biosimilar and its reference product; it does not apply to other biosimilars for the same reference product. Manufacturers may be deterred from pursuing an interchangeable designation for a biosimilar because of additional burdens (eg, the potential need for switching studies) and the substantial cost of generating necessary evidence. Notably, however, when insulins were redefined as biologics, the specific FDA guidance indicated that switching studies with these therapies may be unnecessary to achieve interchangeable status.

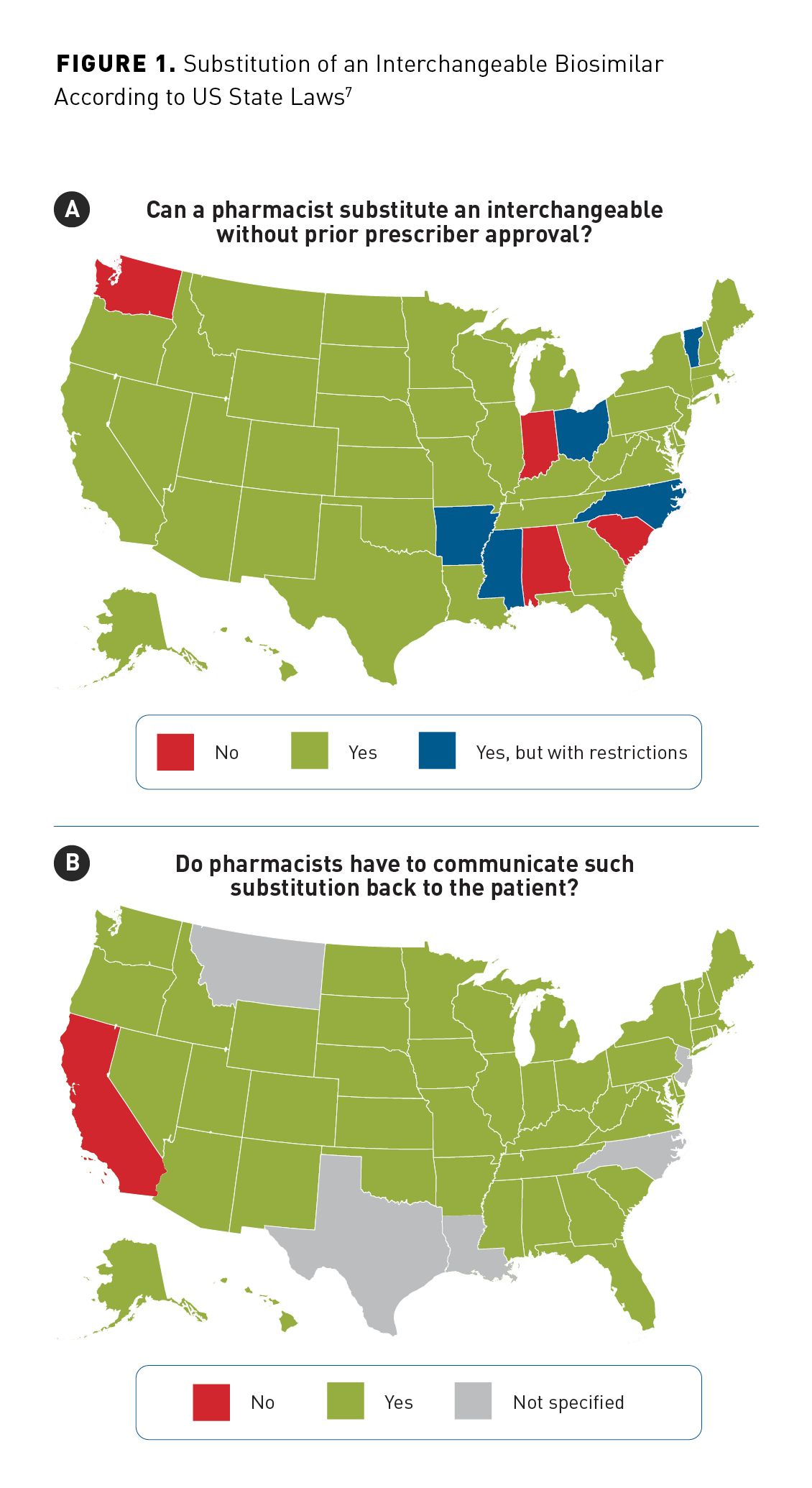

This 2-tiered regulatory categorization creates additional confusion for patients, physicians, and pharmacists, in that a biosimilar cannot be substituted for a reference product at the pharmacy level unless it has been further designated as an interchangeable biosimilar; it then can be substituted according to state law. All US states except Alabama, Indiana, South Carolina, and Washington State authorize a pharmacist to substitute an FDA-approved interchangeable biosimilar for a prescribed reference product unless the prescriber indicates “do not substitute” or “dispense as written” on the prescription (Figure 1a).7 Further, Arkansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, and Vermont have additional cost-related restrictions (eg, only permitted if the substituted product results in lower costs to the patient).7 The majority of states have laws that require that the pharmacy communicate the substitution back to the prescribing health care provider (HCP).6 It is important for pharmacists to recognize these differences and understand whether a provider must be notified after the substitution is dispensed or must give permission before the biosimilar is substituted. The pharmacist will also need to comply with state requirements for communicating the substitution back to the patient (Figure 1b).7

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) included a patent resolution framework with a process for identifying and resolving patents for litigation.8 Despite this, the highly profitable nature of reference biologics can encourage companies to create barriers to biosimilar development, delaying the introduction of biosimilar competitors.9 As a result, some biosimilars that have been FDA-approved are not actually available, or their introduction has been delayed, owing to legal agreements or legal disputes.10

Prescribing and Reporting Issues

The concept of a biosimilar as equivalent in terms of efficacy with comparable safety to the reference product is more widely known and accepted by managed care professionals than in the past. In the 2020 AMCP Foundation survey, 87% of the responding 174 managed care pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and specialty pharmacists agreed or strongly agreed that switching from a reference product to a biosimilar was safe and effective compared with only 7% who disagreed or strongly disagreed.2 However, among HCPs, acceptance of biosimilars and understanding of their approval via extrapolation and the totality of evidence may be more familiar to specialists (eg, medical dermatologists, rheumatologists, and oncologists) who may use more commonly administered biologics than other HCPs (eg, surgical or cosmetic dermatologists). Findings from a 2017 survey of 97 US dermatologists showed that only 37% were aware that a biosimilar is highly comparable to a US-licensed reference product, and only 25% said they would be likely to prescribe a biosimilar.11 Biosimilar uptake across different therapeutic areas can also be affected by differences in specialty practice preferences and multiple guidelines issued by different organizations that may not always be aligned. The situation may be further complicated by attempts to “muddy the waters” by manufacturers of reference products using language that implies safety and efficacy issues with biosimilars, contrary to the very definition of a biosimilar from the FDA.12-14

A lack of traditional clinical trial data is not considered to be the barrier to biosimilar use that it was in the past. Biosimilars are intentionally highly similar to the reference products, meaning that no meaningful clinical differences exist, and data from a large number of patients would be required to detect differences in rare adverse events emerging between the biosimilar and reference product. Postmarketing surveillance, therefore, is needed to monitor for these rare adverse events, and it is required by the European Medicines Agency of the European Union but not by the FDA. However, as with any new treatment, there is always a delay before real-world clinical data from registries, insurance claims records, electronic health care records, and other sources (eg, pragmatic trials) become available. In the AMCP Foundation survey, 91% of responding pharmacists agreed or strongly agreed that real-world evidence of this sort is important to overcome barriers to biosimilar adoption.2 Fortunately, there is a mounting body of real-world evidence in support of biosimilars, with over 15 years of data on their use in clinical practice available for European patient populations.

Physicians and other prescribers are more likely to prescribe the treatments that they are familiar with, and it may take time for prescribing preferences to change.15 Further, there may be an initial reluctance to prescribe treatments for indications extrapolated from equivalence studies related to other indications until further evidence is available.16 Treatment inertia may also be an issue—physicians and other prescribers may not want to switch a patient who is already on a reference product to the biosimilar for nonmedical reasons.17 Further, patients may not be comfortable moving from the treatment they know to a new treatment that offers no medical benefit.18 (Please see the first article in this supplement for more details on nonmedical switching.4) This view is broadly shared by physicians, who may be reticent to initiate switching in patients who are stable on their current biologic therapy. For example, a survey of 320 board-certified US rheumatologists indicated a preference for using biosimilars when newly initiating treatment rather than switching treatments in existing patients.17 However, no matter how accepting of biosimilars physicians become, their prescribing is often limited by formulary restrictions and insurance-related issues.

Expensive therapeutics often require prior authorization (PA) from the patient’s insurance plan. If the provider’s administrative burden for a biosimilar is not less than that for a reference product, the provider is not incentivized to prescribe the biosimilar. The PA pathways could be used to simplify administrative barriers in a way similar to that used for complex specialty medications. Ideally, from an HCP’s point of view, PA requirements would be eliminated for biosimilars when used for an approved or extrapolated indication. A less favorable alternative might include a streamlined PA process or assurance that the patient’s out-of-pocket cost would be limited to a reasonable amount, as even biosimilars can be prohibitively expensive for the average patient if they have to pay a substantial percentage of the cost (eg, coinsurance, deductible).

Another less preferable option would be to add step-therapy rules requiring failure of a preferred biosimilar before the reference drug is approved. Many states have laws regulating step therapy or requiring exceptions in certain situations (eg, life-threatening diseases). Medicare, Medicaid, and other federally backed plans (eg, Tricare) generally do not allow the use of co-pay assistance cards, patient assistance programs, and the like, which could be a challenge in controlling patient out-of-pocket expenditures. Medicare Part D members, who pay for prescription drug coverage through the Medicare program, are subject to the “donut hole” (in 2022, a gap in medication coverage after the patient has spent $4430).19 This can lead to prohibitive out-of-pocket costs, even for a covered biosimilar, early in the year. Medicare members without Part D coverage would likely find any biosimilar cost prohibitive.

Operational Issues

By definition, a biosimilar is not intended to improve on the original reference product and should be all but identical in terms of efficacy and safety. Thus, the primary benefit of biosimilars to society is the potential for cost reduction. The availability of biosimilars and the competition they bring are also associated with wider use of biologics as a whole, implying improved access.20 Despite this obvious advantage, biosimilar adoption in the United States has been substantially slower than their uptake in Europe; this difference goes beyond the earlier approval of biosimilars in Europe, and is, in part, a reflection of the fundamental differences between the European and US health care models.21 Almost all European countries have some form of universal health care or national health service; this integrated approach means that all cost savings from the use of a cheaper alternative, such as a biosimilar, directly benefits the system. Thus, there is a strong financial driver towards the use biosimilars, when available, unless the cost of the reference product is reduced to keep it competitive.

Both the Veterans Administration (VA) and Kaiser Permanente health care systems show substantially more widespread adoption of biosimilars than the general level of uptake in the United States.22,23 Kaiser is a closed health care maintenance organization (HMO) that owns the provider network and employs its own physicians and pharmacists in an integrated health care model; all benefits and cost savings are internal to the Kaiser system, making biosimilars a logical choice to reduce treatment costs. The US VA is a form of nationalized health care service that owns and operates all of its own medical facilities and directly employs HCPs and staff; again, any cost savings from switching to biosimilars are realized as direct savings to the organization. As with the national health care systems in Europe, these integrated health care organizations differ from health care models seen across most of the US health care market, in which private companies occupy different roles that link the patient, payer, and prescriber.

The majority of the US health care market is a nonintegrated patchwork of for-profit and not-for-profit health care systems. Payment for biologic treatment is sometimes managed in a buy-and-bill system, in which a health system purchases medication and then bills the patient’s insurance or payer after treatment has been administered in an outpatient setting (eg, a physician’s office, an infusion center). In dermatology and some other specialties, biologics are not usually administered in this way, but, instead, through the normal prescription-pharmacy pathway used for many other medications. In a properly functioning and truly competitive market, subsidies should not be required to encourage use of a lower cost alternative such as a biosimilar, and manufacturers of reference products could be expected to reduce their pricing to compete. However, various mechanisms within the buy-and-bill system can counterintuitively encourage use of a more expensive medication to realize an immediate benefit, and the (overall) increased cost is passed on elsewhere in the system.

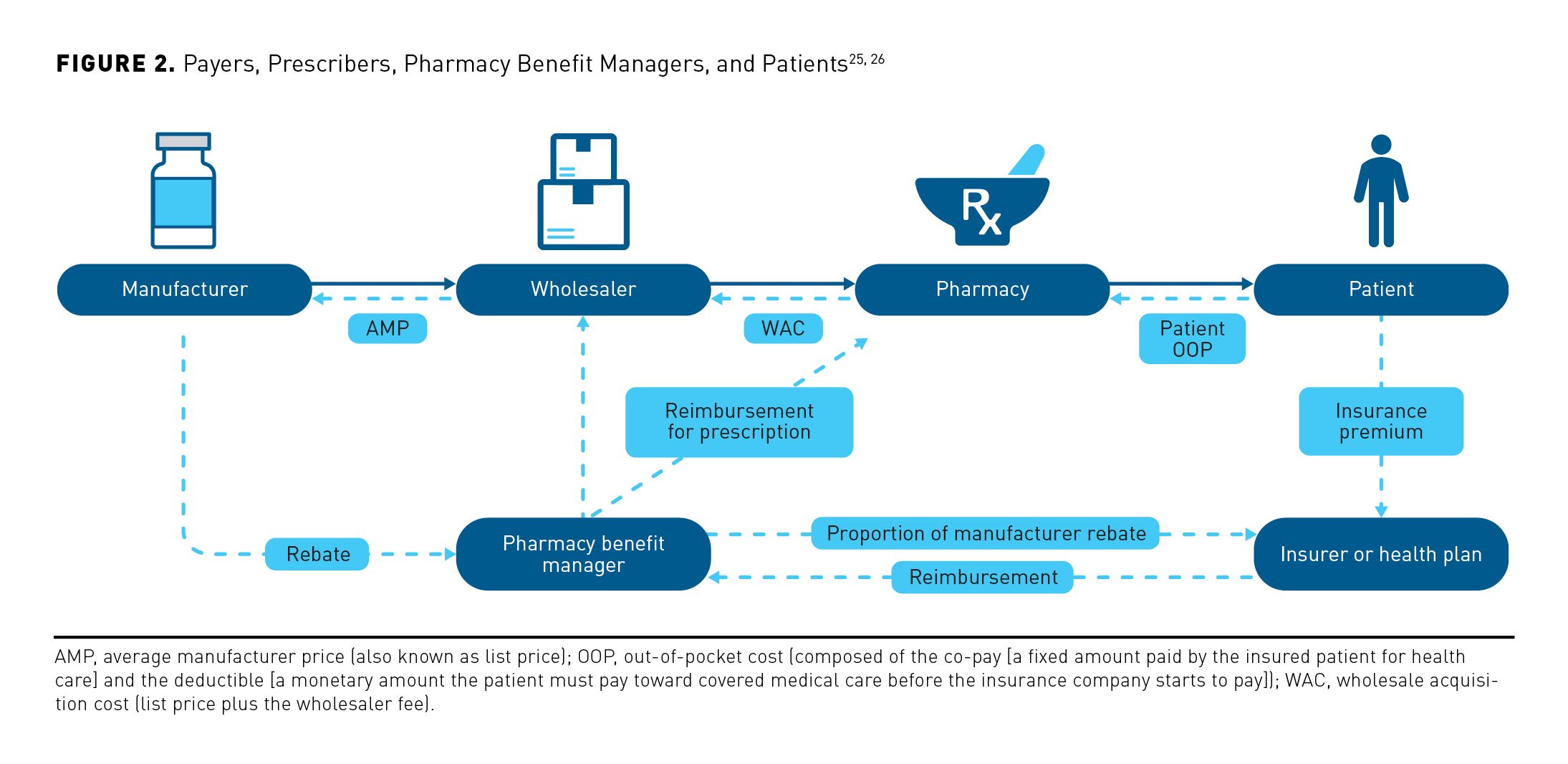

Historically, PBMs were created to leverage purchasing power to obtain better drug prices. Today, PBMs have a role as drug-benefit gatekeepers for over 270 million Americans who have prescription drug coverage, placing them in a key position within the health care financial and distribution pathways (Figure 2).24-26 Payment from the payer to the PBM is often based on list price or the average sales price (ASP) plus a percentage; importantly, this measure of treatment cost does not consider the effects of any pricing program discounts or rebates. Pharmaceutical companies are often obliged to offer rebates to PBMs to be included in the formulary or to be included at a lower tier, recovering the cost of this rebate in the form of a higher list price for the treatment. Both the remuneration from the payer based on a higher ASP and the rebate offered by the pharmaceutical company effectively incentivize PBMs to prefer a more expensive treatment, as it increases their profit.27 In turn, drug manufacturers may be incentivized to increase list prices for treatments to encourage PBMs by offering them higher rebates.28 Contracts may stipulate that a portion of the rebate obtained must be shared with the HCP, but this can be circumvented through the use of “rebate aggregator” companies that receive the full rebate generated but then only share a portion with PBMs, who, in turn, only have to return a part of that portion to the provider.9

When biosimilars are added to formularies, their availability may be further complicated by formulary tiering, in which treatments listed in lower tiers and considered to be preferred elicit a lower co-pay than higher tiered items. Although ostensibly intended to direct prescribers to less expensive treatments, positioning on the formulary tier list can also be affected by rebate agreements and other mechanisms that are not visible to the prescriber or patient. Consequentially, biosimilars may be included on the formulary list at a higher tier than the reference product, resulting in a higher co-pay and thereby making them less accessible or affordable to the patient. In addition to the reference product being able to leverage its established use across multiple indications to obtain a preferred tier status, in some cases, contractual terms or exclusionary rebates have been used to prevent biosimilars from being included on the formulary or in the same tier, resulting in higher co-pay costs to the patient for the biosimilar, even when the biosimilar itself is the less expensive treatment.29,30

In some cases, direct financial incentives to the patient may be offered to overcome reticence to nonmedical switching to lower-tier treatments. In 1 case, a $500 gift card was offered to encourage patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis to switch from secukinumab to ixekizumab (both IL-17A inhibitors), and a similar promotion was offered for infliximab biosimilars.31,32 However, this type of incentive to the patient is forbidden for patients covered by federally backed insurance plans, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

This labyrinthine structure of contracts and payments within the system can lead to a lack of cost transparency for patients and prescribers, who, in some cases, may see little, if any, benefit from the reduced treatment cost associated with a biosimilar. Ultimately, the practical and cost barriers inherent to the US health care system are currently more critical than the regulatory and legal ones; costs within the existing system are the main deciding factor, despite these benefits not being visible to the HCP or patient.

Changes to benefit design, such as enhanced reimbursement models, could encourage PBMs to revise formulary arrangements. Multiple specialty tiers would allow favorable placement from a patient’s cost share perspective or even remove cost share entirely, as has been seen with insulins put into generic tiers to lower out-of-pocket costs.33 Alternative reimbursement models could be used that reward providers for choosing best-value options, such as biosimilars. However, similar attempts with HMOs in the 1980s and, more recently, in medical homes and accountable care organizations have failed to lower costs in this arena.34 Providers have their own preferred products/suppliers, and this can act as a barrier; reimbursing a higher amount for the biosimilars than for the reference product could help counter this problem. However, many of these proposed solutions would only patch aspects of the existing system, and PBMs are likely to continue to influence treatment decisions to their own financial benefit.

Inclusion of biosimilars can increase the complexity of treatment models, with both the increased number of available treatments and variations between different health plans adding to the complexity facing managed care. For example, adding and retaining multiple biosimilars within formulary systems incur an administrative burden; regular updates would mean that few HCPs could hope to proactively keep up with all of the changes across multiple plans and carriers.

Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs and Financial Support

Most patients receive their medications through commercial insurance, state-provided Medicaid insurance, or the federal Medicare program. Insurance typically pays most of the cost, but required co-pay and deductible costs can still be prohibitive. Many reference product manufacturers offer co-pay support programs, and biosimilar manufacturers are incentivized to do the same.35

There is an access issue for Medicare patients, who are not eligible for many patient assistance programs, and this also applies to patients with Medicaid (although co-payment costs are generally lower for this group) and such federal programs as Tricare.36-38 Some pharmaceutical manufacturer benefit programs exist that may be able to provide assistance to federally insured individuals as well as the privately insured and uninsured, but not everyone knows about them.39,40

Payers may prefer biosimilars, but this can create barriers to patients that prevent them from accessing support programs. For example, if a payer were to prefer a rituximab biosimilar that does not have a labeled indication for rheumatoid arthritis, patients would be prevented from accessing manufacturer-led patient assistance programs, as it would be “off label” use, and thus would incur an increased financial burden. Routine patient out-of-pocket costs (eg, deductible, coinsurance) for reference biologics and biosimilars commonly can be hundreds or thousands of dollars, given the high list prices of these treatments. Patient assistance would need to be robust enough to counteract most of these out-of-pocket costs to make treatment realistic.

Conclusion

Looking through the convoluted lens of health care supply chain, regulatory, and administrative issues, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that the entire system was originally intended to serve patients. Choice of treatment may not be in their hands, and even the prescriber may be limited by options that their pharmacy or the insurer provides. Ultimately, it is the patient who will not only take the treatment but also pay the out-of-pocket costs. Formulary placements already impact out-of-pocket costs, which can be very high, especially for uninsured or underinsured patients. It is clear that the current system is not always functioning to the benefit of the patient.

In an ideal system, lower drug costs would always result in reduced cost for the patient. In the case of biosimilars, where lower cost is not achieved at the expense of efficacy or safety, this would result in the less expensive product being preferred, and the reference product price could be expected to decrease to provide competition.

In the long run, regulatory reform and legislative changes may be needed to mitigate the cumbersome financial mechanisms distorting the health care market in the United States. Until then, addressing the current lack of transparency with regards to drug pricing, rebates, and fees would greatly help prescribers to make value-based decisions that would ultimately benefit their patients. Other changes that would help to simplify the existing system would be the introduction of more logical formulary structures, the reduction or elimination of cost-sharing for patients, and the alteration of PA pathways to reduce administrative burden, which would help to remove some of the critical barriers to biosimilar adoption. These changes would help to better align existing incentives for providers, physicians, and payers, such that they drive adoption of the best available care at the lowest cost.

Acknowledgments

The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors received no direct compensation related to the development of the manuscript. Writing, editorial support, and formatting assistance was provided by Andy Shepherd, PhD, CMPP, of Elevate Scientific Solutions, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI). BIPI was given the opportunity to review this manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Data Sharing

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analyzed in this report.

Author Affiliations: National Psoriasis Foundation (former/retired; CE), Austin, TX; Weill Cornell Medicine and Hospital for Special Surgery (AG), New York, NY; Division of Immunology & Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University (VS), Palo Alto, CA.

Author ORCID iD: Vibeke Strand, MD (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4978-4072).

Funding Source: This supplement was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Author Disclosures: Dr Evans reports serving as a volunteer board member for the National Psoriasis Foundation and serving as a consultant or paid advisory board member for Celgene. He has received honoraria from Celgene and Cigna, and he reports being on the speakers’ bureau for AbbVie and Celgene. Dr Gibofsky reports serving as a consultant/advisor to AbbVie, Biosplice Therapeutics, Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer; he reports being on the speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Amgen, and Pfizer; and he reports owning stock in AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer. Dr Strand reports serving as a consultant/advisor for AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Aria Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bioventus, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celltrion, ChemoCentryx, EMD Serono, Endo, Equillium, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Horizon, Ichnos Sciences, Inmedix, Janssen, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, Kypha, Lilly, Merck, MiMedx, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Rheos Medicines, R-Pharm US, Samsung, Sandoz, Sanofi, Scipher Medicine, Servier Pharmaceuticals, SetPoint Medical, Sorrento Therapeutics, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

Authorship Information: Analysis and interpretation of data (CE, AG, VS); drafting of the manuscript (CE, AG, VS); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (CE, AG, VS).

Address Correspondence to: Colby Evans, MD. Email: colbyevans@hotmail.com

References

1. Greene L, Singh RM, Carden MJ, Pardo CO, Lichtenstein GR. Strategies for overcoming barriers to adopting biosimilars and achieving goals of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act: a survey of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(8):904-912. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.18412

2. Eichenbrenner PJ. Managed care stakeholders’ opinions: strategies and barriers to biosimilar adoption. Data presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Partnership Forum; December 15, 2020; Virtual.

3. Remarks by Acting Commissioner Woodcock to the Association for Accessible Medicines 2021Access! Conference. FDA. 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/speeches-fda-officials/remarks-acting-commissioner-woodcock-association-accessible-medicines-2021access-conference-05262021

4. Strand V; Evans C; Gibofsky A. Overview of biosimilars for immune-mediated mediated inflammatory diseases: summary of current evidence. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(suppl 12):S217-S226.

5. Purple Book: database of licensed biological products. FDA. Updated May 6, 2022. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://purplebooksearch.fda.gov/

6. Biosimilars and interchangeable products. FDA. Updated October 23, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products

7. State laws for biosimilar interchangeability. CardinalHealth. Updated July 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.cardinalhealth.com/en/product-solutions/pharmaceutical-products/biosimilars/state-regulations-for-biosimilar.html

8. Rai AK, Price WN 2nd. An administrative fix for manufacturing process patent thickets. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39(1):20-22. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-00780-9

9. Shepherd J. Pharmacy benefit managers, rebates, and drug prices: conflicts of interest in the market for prescription drugs. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2020;38(357).

10. New deal keeps Humira competitors off US shores till 2023. The Pharma Letter. Updated May 4, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.thepharmaletter.com/article/new-deal-keeps-humira-competitors-off-us-shores-till-2023

11. Barsell A, Rengifo-Pardo M, Ehrlich A. A survey assessment of US dermatologists’ perception of biosimilars. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(6):612-615.

12. Building a wall against biosimilars. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(4):264. doi:10.1038/nbt.2550

13. Cohen HP, McCabe D. Combatting misinformation on biosimilars and preparing the market for them can save the U.S. billions. Stat News. June 19, 2019. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.statnews.com/2019/06/19/misinformation-biosimilars-market-preparation

14. FDA guidance sought on false and misleading information on biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilar Initiative. July 9, 2018. August 5, 2022. https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/FDA-guidance-sought-on-false-and-misleading-information-on-biosimilars

15. Nabhan C, Feinberg BA. Behavioral economics and the future of biosimilars. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(12):1449-1451. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2017.7023

16. Kozlowski S, Flowers N, Birger N, et al. Uptake and usage patterns of biosimilar infliximab in the Medicare population. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):2170-2173. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05957-1

17. Gibofsky A, McCabe D. US rheumatologists’ beliefs and knowledge about biosimilars: a survey. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(2):896-901. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keaa502

18. Gibofsky A, Jacobson G, Franklin A, et al. Attitudes about biosimilars among US patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or inflammatory bowel disease: an online survey. Paper presented at: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus 2021; October 18-21, 2021; Denver, CO.

19. Costs in the coverage gap. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap

20. Di Giuseppe D, Frisell T, Ernestam S, et al. Uptake of rheumatology biosimilars in the absence of forced switching. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(5):499-504. doi:10.1080/14712598.2018.1458089

21. Brill A, Robinson C. Lessons for the United States from Europe’s biosimilar experience. The Biosimilars Council. June 2020. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://biosimilarscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/EuropeBiosimilars_June_2020.pdf

22. Baker JF, Leonard CE, Lo Re V 3rd, Weisman MH, George MD, Kay J. Biosimilar uptake in academic and veterans health administration settings: influence of institutional incentives. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(7):1067-1071. doi:10.1002/art.41277

23. How did Kaiser Permanente reach 95%+ utilization of biosimilar Herceptin and Avastin so quickly? BR&R Biosimilars Review & Report. Updated December 4, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://biosimilarsrr.com/2019/11/07/

24. Berchick ER, Barnett JC, Upton RD. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2018. US Census Bureau. November 2019. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-267.pdf

25. National Community Pharmacists Association. Concerns regarding the pharmacy benefit management industry. November 2015. Accessed September 30, 2021. http://www.ncpa.co/pdf/applied-policy-issue-brief.pdf

26. Bridges SL Jr, White DW, Worthing AB, et al. The science behind biosimilars: entering a new era of biologic therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(3):334-344. doi: 10.1002/art.40388

27. Seeley E, Kesselheim AS. Pharmacy benefit managers: practices, controversies, and what lies ahead. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2019;2019:1-11.

28. Fein AJ. New data show the gross-to-net rebate bubble growing even bigger. Drug Channels Institute. June 14, 2017. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://perma.cc/6MFF-M625

29. Parsons L. J&J and Pfizer quietly resolve Remicade biosimilar lawsuit. PMLive. July 27, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.pmlive.com/pharma_news/j_and_j_and_pfizer_quietly_resolve_remicade_biosimilar_lawsuit_1373692

30. Mehr S. Contracting “schemes” to prevent biosimilar infliximab access: let’s drop the feigned outrage. BR&R Biosimilars Review & Report. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://biosimilarsrr.com/2018/07/18/contracting-prevent-biosimilar-infliximab-access/

31. Inserro A. Cigna dangles $500 to persuade patients to switch psoriasis drugs. AJMC®. March 26, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.ajmc.com/view/express-scripts-dangles-500-to-persuade-patients-to-switch-psoriasis-drugs

32. Minemeyer P. Cigna to offer $500 incentive for members who switch to a biosimilar drug. Fierce Healthcare. June 24, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payer/cigna-to-offer-500-incentive-for-members-who-switch-to-a-biosimilar-drug

33. Nguyen AT, Sawant RV, Serna O, Esse T, Sansgiry SS. Medicare Part D insulin tiering change: impact on health outcomes. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2016;8(5). Pharmacy Times®. October 19, 2016. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/medicare-part-d-insulin-tiering-change-impact-on-health-outcomes

34. Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al. Insulin Access and Affordability Working Group: conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(6):1299-1311. doi:10.2337/dci18-0019

35. Pharmaceutical manufacturer patient assistance program information. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated December 1, 2021. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PAPData

36. 5 ways to get help with prescription costs. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap/6-ways-to-get-help-with-prescription-costs

37. Feke T. Why you can’t use drug coupons with Medicare Part D. Verywell Health. Updated March 6, 2020. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.verywellhealth.com/when-to-use-drug-coupons-4174705

38. Andrews M. Why can’t Medicare patients use drugmakers’ discount coupons? Shots: Health News From NPR. May 9, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/05/09/

609150868/why-cant-medicare-patients-use-drugmakers-discount-coupons?t=1635354674961

39. Reimbursement and support. Pfizer. 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.pfizerpro.com/node/6801

40. Paying for ENBREL: the cost of ENBREL and financial support options. Amgen. Updated January 6, 2022. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.enbrel.com/financial-support