- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

Biosimilars in Focus: Advancing Implementation in Health Care Systems

A biosimilar is a biologic medication that is highly similar to an existing FDA-approved biologic, known as a reference product, with no clinically meaningful differences. Biosimilars are derived from the same types of living sources, administered in the same way, and have the same strength, dosage, therapeutic benefits, and adverse events as the reference product. They can be used in both treatment-experienced patients and those who are treatment naive. As patent protections for many reference biologics expire, biosimilars are expanding as viable alternatives, with the potential to enhance patient access to essential therapies and drive competition within the market. Current prescribing trends indicate a growing acceptance and integration of biosimilars as part of prescribing practices and treatment protocols by health care providers.1

Although the affordability of biosimilars can vary, their introduction generally fosters competitive pricing, which may lead to reduced health care expenditure over time.2 By offering additional options, biosimilars can play a unique role in expanding access to treatments. Between 2015 and 2023, biosimilars were utilized in nearly 700 million patient therapy days without presenting any unique clinical challenges.3 The availability of biosimilars has increased the overall use of molecules with biosimilar competition, indicating that more patients are utilizing these medicines. For example, the market entry of filgrastim biosimilars has led to a 20% increase in dispensed doses, reflecting its expanded access to patients being treated for cancer.3 Biosimilar competition has facilitated over 344 million additional days of therapy, providing care that would have otherwise been inaccessible to patients.

US BIOSIMILAR APPROVAL PROCESS

Within in the US, biologics are the fastest-growing class of medication, representing a substantial and increasing share of health care expenditures. The FDA approves biosimilars through an expedited pathway, with the goal of demonstrating similarity to the reference product rather than conducting extensive independent clinical trials; this results in cost and time savings for manufacturers.4

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 established an expedited approval pathway to improve patient access to safe and effective biologic products while reducing development time and costs. For the approval of a biosimilar product, the FDA evaluates each proposed biosimilar on an individual basis and provides manufacturers with guidance on the required testing to demonstrate biosimilarity.4

INTERCHANGEABILITY

In addition to approving biosimilars, the FDA offers an additional designation, known as interchangeability, that manufacturers may seek.4 This designation is granted based on switching studies that demonstrate the biosimilar can be substituted for the reference product without any significant risk to safety or efficacy. Not all biosimilars are interchangeable, as manufacturers must specifically seek FDA approval for an interchangeable product designation.4 In practice, this means that an interchangeable biosimilar can be substituted at the pharmacy level for the reference product without requiring the intervention of the prescribing health care provider, depending on state pharmacy laws.5 This practice is analogous to the automatic substitution of generic drugs for brand-name drugs.

Manufacturers typically conduct switching studies to compare outcomes between patients treated with the reference product and those who alternate between the reference product and the interchangeable biosimilar. Switching studies help the FDA determine whether a biosimilar is interchangeable, but the studies themselves do not imply improved safety or effectiveness of the biosimilar. Both designations—biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar—are held to the same high standards for quality and similarity to the reference product, as required by the FDA.4

President Joe Biden’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2025 introduces a proposal to streamline the biosimilar approval process and enhance patient access to affordable medications. This initiative aims to amend section 351 of the Public Health Service Act by eliminating the separate statutory requirement for the determination of interchangeability for biosimilars. Currently, the distinction between biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars has caused confusion among patients and health care providers regarding their safety and effectiveness.6

By unifying the standard, all FDA-approved biosimilars will be considered interchangeable with their reference products, removing the need for a separate interchangeability determination. This change aligns the US biosimilar program with that of the European Union and other major regulatory bodies, where biosimilars are deemed interchangeable upon approval. Simplifying biosimilar substitution is expected to boost the adoption of biosimilars, promoting competition and enhancing access to safe and affordable treatments.6

CURRENT US APPROVED BIOSIMILARS

As of July 1, 2024, the FDA has approved 56 biosimilars, though approval does not ensure their market availability.7 Biosimilars are approved for a variety of disease categories, including autoimmune diseases, cancers, and diabetes.

RECENT SPOTLIGHT: ADALIMUMAB BIOSIMILARS

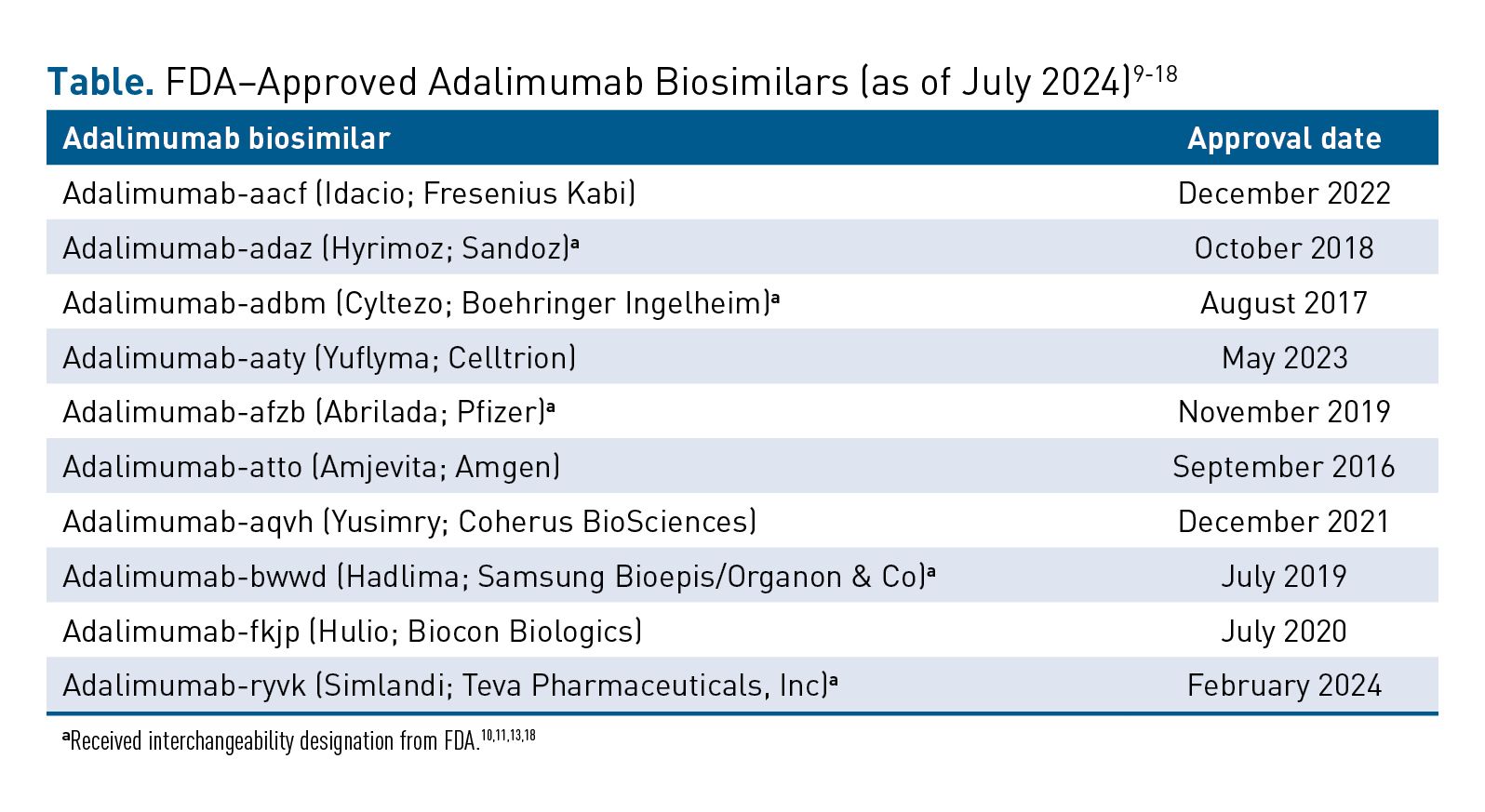

The introduction of adalimumab (Humira; AbbVie) biosimilars marks a significant development in treating autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis.8 The adalimumab reference product is estimated to have generated over $20 billion in 2021 for its manufacturer. As of June 2024, the FDA has approved 10 biosimilars for adalimumab, expanding the treatment options for various autoimmune and inflammatory conditions (Table).9-18

Although biosimilars like adalimumab-atto (Amjevita; Amgen) have been marketed in Europe since 2018, US patents and exclusivity litigation delayed their entry into the US market until recently.8 These biosimilars are available in various forms, including prefilled pens and autoinjectors and prefilled syringes.7

ECONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR BIOSIMILARS

When discussing the pricing dynamics of adalimumab biosimilars, it is essential to understand the differences between average sales price (ASP) and wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), as well as the economic considerations across medical and pharmacy benefit channels.

ASP denotes the average revenue manufacturers receive from wholesalers after discounts and rebates, which is typically lower than the initial WAC set by manufacturers before such deductions. For adalimumab biosimilars, while WAC may initially be set lower to encourage market entry, ASP reflects the actual market price over time as negotiated discounts and rebates come into play.19

In the medical benefit channel, biosimilars may be administered in clinical settings like infusion centers, where payer costs include ASP plus a markup and may also encompass facility fees. This can lead to higher overall expenses due to additional administration costs. On the other hand, under the pharmacy benefit, biosimilars dispensed for self-administration through pharmacies are priced based on agreements negotiated between pharmacies and payers. Initially closer to WAC, these costs can decrease through rebates and patient assistance programs.20

In 2023, the expiration of reference adalimumab’s 20-year market exclusivity heralded the introduction of biosimilar alternatives.14 Amgen launched 2 versions of its adalimumab biosimilar with different WAC price points, setting one 55% below reference adalimumab’s list price and the other 5% below that price.21 The difference in WAC prices is likely due to contract stipulations and rebates offered on the higher WAC adalimumab.21 This gap in understanding underscores the importance of contextualizing biosimilar price announcements and estimating potential cost savings associated with their market introduction.

Between 2013 and 2020, the list price of reference adalimumab significantly increased, while the rebates negotiated with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) also saw a substantial rise. Despite the growing list price, the net prices paid by commercial and Medicare Part D plans showed an initial increase but started to decline toward the end of the period. Medicaid experienced a unique situation where inflation rebates on the original adalimumab became so substantial that they effectively reduced the net price to $0 by 2019. Medicaid inflation rebates, which compensate Medicaid for price increases above inflation, were estimated separately for the adalimumab reference product and the citrate-free version introduced in 2018. Findings reflect that inflation rebates were significantly lower for the citrate-free product, leading to a substantially higher net price for Medicaid.22 This indicates a trend toward increasing list prices and rebates, with variable impacts on net prices across different payer segments.

Despite increasing rebates, the net price of reference adalimumab for commercial and Part D plans in 2020 was $1812, which is 3.5 times its launch price of $522. In 2023, the lowest-cost formulation of adalimumab-atto had a list price of $1558, reflecting a 14% discount from adalimumab’s 2020 net price. Even with a 55% discount, adalimumab-atto’s cost remains more than double reference adalimumab’s launch price. These estimates are constrained by the ability to compare only adalimumab’s 2020 net price with current adalimumabatto pricing and the lack of data to estimate discounts for federal purchasers, which are included under PBM rebates.22 This highlights a trend where new treatments, including biosimilars intended to be more affordable alternatives, still maintain high prices relative to earlier benchmarks.

Biosimilars are becoming increasingly relevant in the context of the 340B Drug Pricing Program in the United States. The 340B Drug Pricing Program is a federal safety-net initiative aimed at supporting health care providers that serve low-income populations.23 Eligible providers, such as general acute nonprofit and public hospitals with a disproportionate share hospital (DSH) percentage above 11.75%, receive significant discounts on drug purchases. These discounts can be substantial, with hospitals often negotiating larger reductions than the mandated minimum of 22.5%.24

Prescription products purchased at these discounted rates can be administered to a wide range of patients, including those covered by Medicare, without regard to their income or ability to pay.23 Despite these discounts, Medicare reimburses 340B hospitals at the same rates as non-340B hospitals, allowing 340B hospitals to potentially earn higher profits.23 The program’s structure may inadvertently incentivize the administration of more expensive, higher-reimbursed drugs, particularly reference biologics, which are often subject to larger discounts compared to biosimilars.25

MARKET TRENDS

Over the past 5 years, the biologics sector has grown 12.5% annually, now representing a sizable portion of total pharmaceutical expenditures. Recent biosimilars have rapidly gained high volume shares, exceeding 60% of the molecule’s volume within 3 years. This growth has created a favorable environment for biosimilars, which provide competitive alternatives to high-cost biologics and have begun to capture significant market share. Projected launches and uptake are anticipated to significantly increase overall spending on biosimilars to $20 billion to $49 billion by 2027, with cumulative sales reaching $129 billion over the next 5 years. The US biosimilars market is expected to experience continued, substantial growth over the next few years, driven by the increasing adoption of biosimilar products and expanding indications.26

Data indicate that biosimilars for molecules such as bevacizumab, trastuzumab, and rituximab have seen rapid uptake, with some achieving notable volume shares shortly after their introduction.26 Biosimilars targeting these and other high-cost biologics are expected to enter the market, contributing to an anticipated biosimilar market valuation of up to $129 billion in the next 4 years. The adoption rates of biosimilars vary across different health care settings, influenced by factors such as reimbursement models and provider preferences.27

Looking forward, policy changes and payer strategies will play critical roles in this expansion, as they will determine coverage and out-of-pocket costs for patients.27 As these dynamics evolve, the potential for biosimilars to provide cost savings and increase patient access to essential therapies remains significant.26 The market outlook remains optimistic, with biosimilars anticipated to encompass growing shares of the market and see higher utilization in the US health care system.

POLICY TRENDS

CMS is implementing a temporary payment increase for certain biosimilars covered under Medicare Part B. Normally, Medicare reimburses biosimilars at ASP plus 6% of the reference biological product’s ASP in settings like physicians’ offices and outpatient departments. Effective October 1, 2022, qualifying biosimilars receive ASP plus 8% of the reference biologic product’s ASP for a period of 5 years, as stipulated by Section 11403 of the Inflation Reduction Act.28

The aim of this change is to boost accessibility to biosimilars and foster market competition, potentially lowering health care costs. Although Medicare beneficiaries might experience a slight uptick in cost sharing, this increase is anticipated to be modest and could be mitigated by factors such as supplemental coverage or regular fluctuations in drug prices. This temporary payment adjustment applies to biosimilars administered in physicians’ offices, hospital outpatient departments, and ambulatory surgical centers. The number of qualifying biosimilars eligible for this enhanced payment may vary each quarter based on their ASP in relation to the reference biologic product. While this policy maintains existing Medicare coverage rules, its objective is to encourage competition in the market, leading to potential savings on biosimilars and other biologic products, and expanding patient access to these treatments.28

BIOSIMILAR UTILIZATION IN HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS

Strategic initiatives have been adopted by various health care systems to enhance the utilization of biosimilars. Sophia Humphreys, PharmD, MHA, BCBBS, who collaborated with a diverse team at Providence St. Joseph Health system in Rhode Island, presents a detailed account of the process of integrating biosimilars into her health care system, highlighting the outcomes in reducing biologic drug costs and promoting biosimilar adoption.29

Implemented across 7 originator biologics, the program involved expedited formulary reviews, enhanced contracting strategies, and the use of electronic health record (EHR) tools to guide physician prescribing. Key initiatives included identifying high-cost biologics nearing patent expiration, streamlining the formulary review process, and integrating EHR tools to encourage the prescribing of biosimilars. These measures were supported by comprehensive provider communication and patient education to address uncertainties regarding biosimilar efficacy and safety. From January 2019 to November 2020, these strategic efforts resulted in $26.9 million in savings and a 62% biosimilar adoption. The program’s success is evident in the notable reduction of originator biologic purchases and the high adoption rates of biosimilars like filgrastim and pegfilgrastim, which saw the most significant uptake, at adoption rates of 74.2% and 73.4%, respectively.29

The success of Providence St. Joseph Health’s biosimilar utilization management program underscores the potential for substantial cost savings and enhanced sustainability in health care systems. By fostering collaboration among multidisciplinary teams and leveraging data-driven performance evaluations, the program not only reduced expenditures on biologic medications but also helped facilitate high-quality patient care. This model highlights the critical role of strategic management and technology in optimizing drug utilization and achieving financial efficiencies in health care.29

CONCLUSIONS

The emergence and integration of biosimilars into the health care market signifies a pivotal advancement in expanding access to essential treatments and promoting cost savings. The approval and use of biosimilars, including those for adalimumab, demonstrate their potential to provide safe and effective alternatives to reference biologics while fostering competitive pricing. Despite challenges in market penetration and patient access, biosimilars are increasingly accepted among health care providers, highlighting their critical role in transforming health care economics. Efforts to streamline regulatory processes and enhance interchangeability are expected to further support the adoption of biosimilars, ultimately benefiting patients and the broader health care system.

REFERENCES

1. Overview for health care professionals. FDA. January 18, 2024. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/overview-health-care-3

2. Biosimilars action plan. FDA. April 26, 2024. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilars-action-plan

3. The U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report Association for Accessible Medicines. September, 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://accessiblemeds.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/AAM-2023-Generic-Biosimilar-Medicines-Savings-Report-web.pdf

4. Review and approval. FDA. December 13, 2022. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/review-and-approval

5. Biosimilar and interchangeable biologics: more treatment choices. FDA. August 17, 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/biosimilar-and-interchangeablebiologics-more-treatment-choices

6. Fiscal Year 2025: Budget in Brief. US Department of Health & Human Services. March 11, 2024. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2025-budget-in-brief.pdf

7. Biosimilar drug information. FDA. Updated July 22, 2024. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information

8. New competition for Humira. Arthritis Foundation. January 27, 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.arthritis.org/news/news-and-events/humira-biosimilars

9. Idacio. Prescribing information. Fresenius Kabi USA LLC.; 2022. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761255s000lbl.pdf

10. Hyrimoz. Prescribing information. Sandoz Inc; 2018. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761071lbl.pdf

11. Cyltezo. Prescribing information. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2024. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://content.boehringer-ingelheim.com/DAM/9d0e3bae-9a17-4979-91bcaf1e011eeb8a/cyltezo-us-pi.pdf

12. Yuflyma. Prescribing information. Celltrion, Inc; 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/761219s000lbl.pdf

13. Abrilada. Prescribing information. Pfizer Inc; 2024. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=12780

14. Amjevita. Prescribing information. Amgen Inc; 2016. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/761024lbl.pdf

15. Yusimry. Prescribing information. Coherus BioSciences; 2021. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761216s000lbl.pdf

16. Hadlima. Prescribing information; Bioepis Co, Ltd; 2019. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761059s000lbl.pdf

17. Hulio. Prescribing information. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc;2020. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761154s000lbl.pdf

18. Simlandi. Prescribing information. Alvotech USA; 2024. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www. accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761299s000lbl.pdf

19. Part B drug payment limits overview. CMS. Updated April 2, 2024. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/part-b-drug-payment-limits-overview.pdf-0

20. 2022 Medicare Parts A & B premiums and deductibles/2022 Medicare Part D income-related monthly adjustment amounts. CMS. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2022-medicare-parts-b-premiums-and-deductibles2022-medicare-part-d-income-relatedmonthly-adjustment

21. Amjevita (adalimumab-atto), first biosimilar to Humira, now available in the United States. News release. Amgen. January 31, 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.amgen.com/newsroom/press-releases/2023/01/amjevita-adalimumabatto-first-biosimilar-to-humira-now-available-in-theunited-states

22. Dickson SR, Gabriel N, Hernandez I. Contextualizing the price of biosimilar adalimumab based on historical rebates for the original formulation of branded adalimumab. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2323398. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23398

23. Disproportionate share hospitals. Health Resources and Services Administration. Updated June 2024. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/hospitals/disproportionate-share-hospitals

24. Medicare program; Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System: remedy for the 340B-acquired drug payment policy for calendar years 2018-2022. Fed Regist. 2023;215(88):77150-77194. November 8, 2023. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/11/08/2023-24407/medicare-program-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-system-remedy-for-the-340b-acquired-drug

25. Maxwell A. Biosimilars Have Lowered Costs for Medicare Part B and Enrollees, but Opportunities for Substantial Spending Reductions Still Exist. Office of Inspector General. September2023. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/evaluation/2947/OEI-05-22-00140-Complete%20Report.pdf

26. Biosimilars in the United States 2023-2027. IQVIA Institute. January 31, 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/biosimilars-inthe-united-states-2023-2027

27. Oskouei ST, Kusmierczyk AR. Biosimilar uptake: the importance of healthcare provider education. Pharmaceut Med. 2021;35(4):215-224. doi:10.1007/s40290-021-00396-7

28. Frequently asked questions: Inflation Reduction Act Biosimilars temporary payment increase. CMS. 2022. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/biosimilar-faqs.pdf

29. Humphreys SZ. Real-world evidence of a successful biosimilar adoption program. Future Oncol. 2022;18(16):1997-2006. doi:10.2217/fon-2021-1584.