- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

An Overview of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid and Alcohol Use Disorders

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS (SUDS) are common causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States and place substantial burdens on society in terms of productivity loss, healthcare utilization, and crime.1

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is broadly characterized by the continued use of opioids despite the associated problematic consequences.2 Similarly, alcohol use disorder (AUD) is characterized by problematic alcohol use in which the patient cannot control its intake and experiences negative emotional symptoms when not using alcohol.3 Both disorders are diagnosed based on a set of criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition.2

OUD is an epidemic in the United States,4,5 and data show that AUD is also on the rise.6 However, SUDs are preventable and treatable. Medication and counseling treatment (MAT) is an evidence-based treatment approach to SUD that involves use of medications in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies to improve patient outcomes in this population.7

Although the public health and societal threats of SUDs provoke the need for a comprehensive treatment approach,4 data have demonstrated low rates of MAT use.7,8 MAT is underused mainly because of lack of access to opioid maintenance programs, lack of training for providers, and stigma.9-12

Medication and Counseling Treatment

Medications Used in MAT

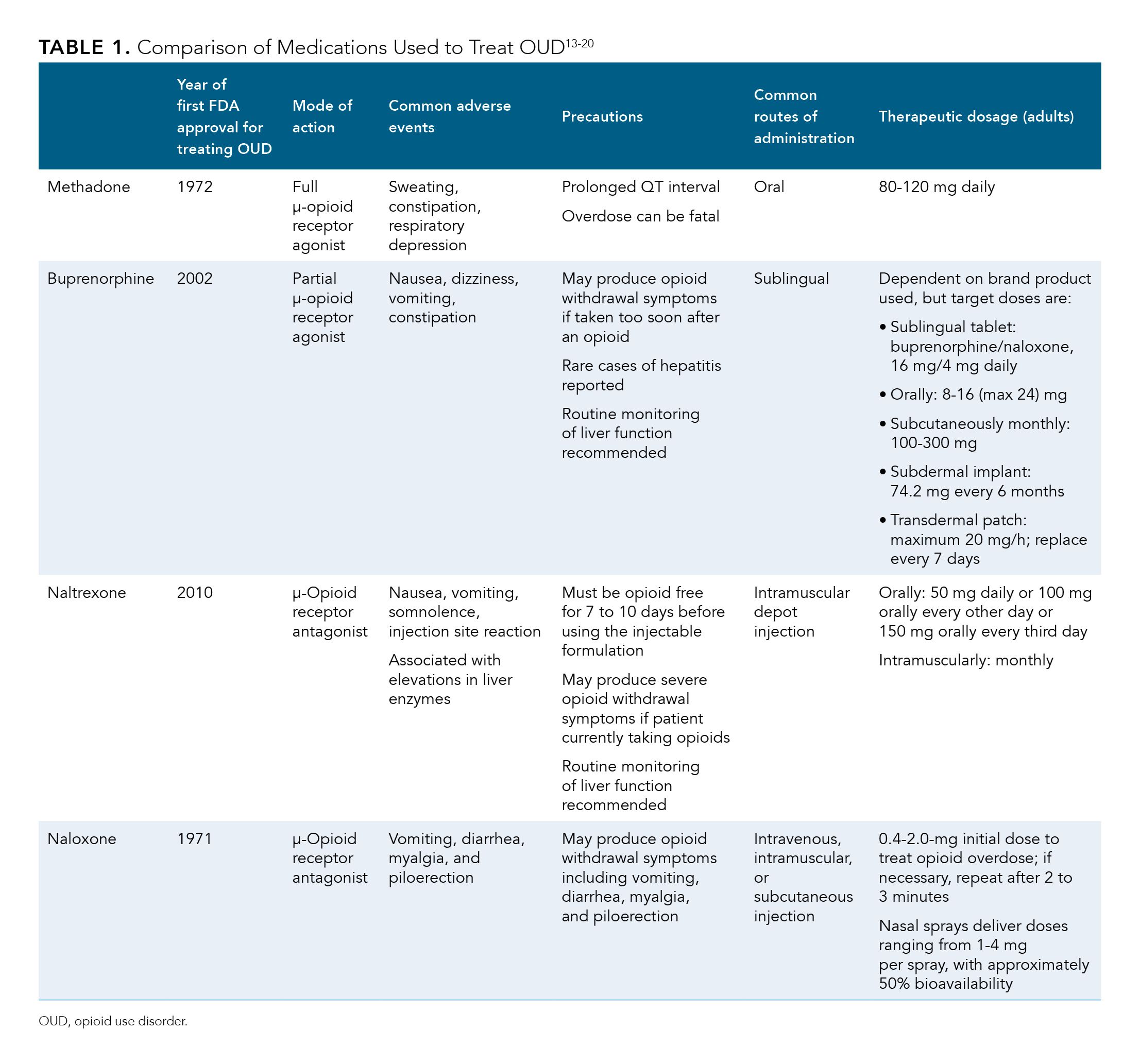

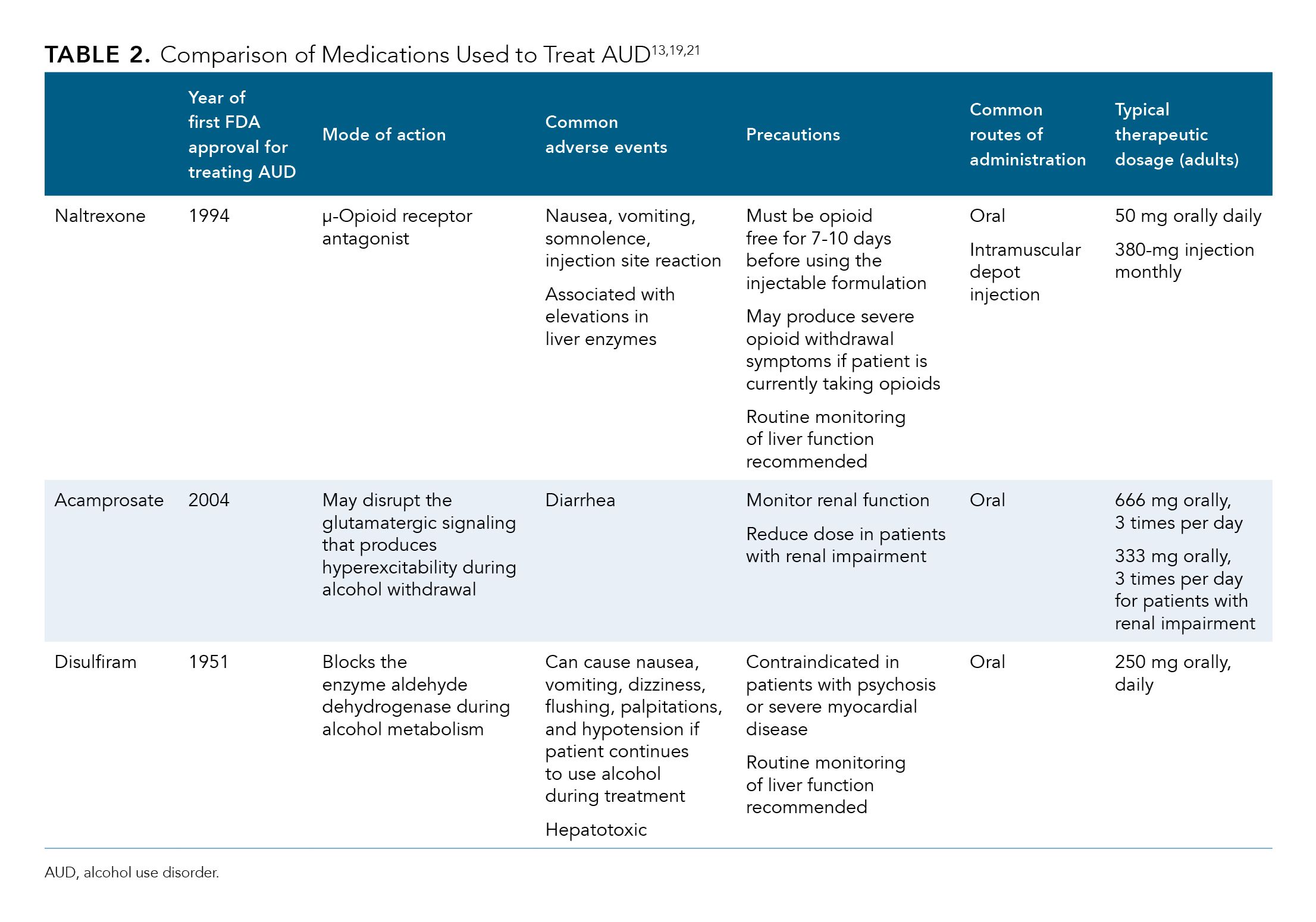

Currently, 3 drugs are approved by the FDA for treatment of OUD, and 3 are approved for AUD. Characteristics of these drugs, including dosing, administration, and common adverse events, are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.11-21

Our Medications

Methadone has traditionally been considered the standard treatment for OUD,13 and patients can receive it only from federally regulated licensed outpatient opioid treatment programs (OTPs).19 It is typically well tolerated, and its long half-life allows for daily oral administration as methadone maintenance therapy.12,19

As an alternative to methadone, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers in physicians’ offices and, thus, is more widely available to patients. Buprenorphine has a long duration of action because of its high opioid receptor affinity and slow dissociation from the receptor, which may allow for alternate-day dosing.12,19 Patients may take it sublingually, either alone or in combination with naloxone; the latter serves to prevent misuse of the buprenorphine by injection.19 Because buprenorphine is only a partial opioid agonist, symptoms of physical dependence and withdrawal associated with its administration are milder than those that may occur with use of full agonists such as methadone.12

Naltrexone is another treatment option for OUD. Unlike μ-receptor agonists methadone and buprenorphine,19 naltrexone is an antagonist of the μ-opioid receptor13,19 available in oral and injectable formulations.19

Opioid Overdose Prevention Medication

Data have shown that opioid overdoses account for approximately two-thirds of all drug overdose deaths in the United States.22 Naloxone (Table 1)13-20 is a short-acting competitive antagonist of the μ-opioid receptor that can be used to reverse the effects of opioid overdose to save lives.14 Its onset of action is swift, less than 2 minutes in adults when administered intravenously.14 Intramuscular and concentrated intranasal spray formulations are also available.13

Expanding access to naloxone for individuals at risk for opioid overdose represents a key aspect of the public health response to the opioid crisis.22 The CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone to at-risk patients, including those who have a history of overdose or SUD, are being treated with high daily doses of opioids, and/or are concurrently using benzodiazepines.23 Take-home naloxone kits are now also available to offer opioid overdose rescue for those who inject drugs.13

AUD Medications

In addition to its benefit in treating patients with OUD, naltrexone (Table 2)13,19,21 can help to block the effect of alcohol on the opioid receptors, thereby reducing some of the pleasurable effects associated with alcohol use.19

Another available agent, acamprosate, is thought to disrupt the glutamatergic signaling that leads to central nervous system hyperexcitability that patients may experience during alcohol withdrawal. This oral agent may reduce symptoms such as insomnia and anxiety that can often continue to promote alcohol use.19

Disulfiram works by inhibiting the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase, which, when combined with alcohol, causes an aversive reaction. Following alcohol use, serum acetaldehyde levels increase and result in symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, flushing, palpitations, and hypotension, all of which deter further alcohol use.19

Because SUD medications are potentially deadly when taken by children, clinicians should warn patients who are taking MAT medications that these drugs must be stored away from common areas in the home and out of reach of others.20

MAT Effectiveness

A key outcome in treating patients with SUDs is treatment retention. In a Cochrane review of 11 randomized controlled trials, methadone treatment was more effective than nonpharmacological interventions in retaining patients with OUD in treatment and decreasing their heroin use.24 Another systematic review of 55 articles showed that naltrexone or buprenorphine treatment led to better 3-, 6-, and 12-month treatment retention rates for patients with OUD compared with placebo or no medication.12

In a recent retrospective study that examined mortality outcomes in patients with OUD who received methadone, buprenorphine, or implant naltrexone treatment, mortality rates were lower in all treatment groups when patients remained engaged in their treatment than when they discontinued treatment.25

Studies have also demonstrated effectiveness of MAT in patients with AUD. In a study of more than 5700 alcohol-dependent adults with serious mental illness at the 12-month follow-up, patients who received MAT were less likely to require mental health hospitalization and emergency department visits and were more likely to adhere to their psychotropic medications than those who did not receive MAT.7

Overall, engaging individuals with SUDs in MAT is more likely to improve their mental health, quality of life, employability, and family relations as well as decrease their illicit substance use and criminal activity.13 For people who inject drugs, MAT can also help to lower the risk of acquiring infectious diseases, such as HIV and hepatitis C virus.26

Counseling and Behavioral Therapies

Federal law requires MAT to include not only pharmacologic treatments for people with SUDs but also counseling and behavioral therapies from a trained provider27 to engage patients in treatment, change their behaviors, and treat their comorbid mental health disorders.28 Ideally, interventions should be ongoing, patient centered, and tailored to the individual patient’s needs.28

Opioid Treatment Programs

OTPs are federally certified specialty programs that offer a combination of MAT medications and other services to patients with OUD, such as addiction counseling and behavioral therapy. These programs must meet standards from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration certification and accreditation processes21 to administer or directly dispense (but not prescribe) any of the FDA-approved drugs for OUD. Locations offering OTPs are generally the only ones that can dispense methadone for this treatment use.29

Guidelines on Use of MAT

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has released evidence-based practice guidelines for the treatment of AUD and OUD. The most recent AUD guidelines recommend using naltrexone and acamprosate as first-line treatments for certain patients with moderate to severe AUD.30

The APA guidelines recommend a patient-centered treatment approach to AUD and also acknowledge the benefit of psychosocial interventions (including cognitive behavioral therapy, 12-step facilitation, and motivational enhancement therapy) and community-based peer support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous for patients.30

Similarly, although somewhat dated, the APA’s Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorder discusses key strategies for managing OUD in patients, focused on reducing acute symptoms of opioid use and engaging the patient in an ongoing treatment program. These initial management strategies include treating patients with methadone or buprenorphine, followed by a gradual taper, acutely discontinuing opioids and using clonidine to attenuate withdrawal symptoms, and treating with clonidine and naltrexone along with psychosocial interventions.31

Challenges Associated With Accessing MAT

Despite MAT’s effectiveness, patients with SUDs frequently experience multiple barriers to accessing MAT.

At the provider level, for example, recent research has shown that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Buprenorphine Practitioner Locator (a database that patients use to find providers who can provide treatment for OUD) contains many inaccuracies. Among the clinic listings evaluated in the study, approximately 27% contained incorrect telephone numbers, only about 39% actually provided buprenorphine, wait times for appointments were up to 120 days, and fewer than 30% of clinics had available appointments.32

Patients often face logistical challenges regarding MAT, including those related to their accommodation, employment, childcare needs, and transportation requirements. They may also have to overcome societal stigma, not just from friends and family but also from their providers, self-help groups, or even themselves.28 Patients engaged in MAT should know that they are protected by federal antidiscrimination laws under most circumstances.33

Lastly, because the behavioral health care system is underfunded, treatment programs frequently face problems related to financing and reimbursement, including from Medicaid.28

Conclusions

Overall, MAT is a safe and effective approach to help patients rehabilitate from SUDs such as OUD and AUD. Nevertheless, this treatment strategy remains underused and underfunded. Improving availability of MAT and patient access are thus critical for patients, employers, and society, to reduce the burden of illness of SUDs and to improve public health outcomes.

References

1.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Trends and statistics. National Institutes of Health website. Accessed October 8, 2020. drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics

2. Opioid use disorder: what is opioid addiction? Providers Clinical Support Systemwebsite. Published December 6, 2017. Accessed October 8, 2020. pcssnow.org/resource/opioid-use-disorder-opioid-addiction

3. National Institute on Alcohol and Drug Abuse. Alcohol Facts and Statistics. National Institutes of Health website. Accessed October 8, 2020. niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics

4. Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, Cair R. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468-1478. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.11859

5. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063-2066. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1402780

6. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2003 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

7. Robertson AG, Easter MM, Lin H, Frisman LK, Swanson JW, Swartz MS. Medication-assisted treatment for alcohol-dependent adults with serious mental illness and criminal justice involvement: effects on treatment utilization and outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):665-673. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060688

8. Neighbors CJ, Choi S, Healy S, Yerneni R, Sun T, Shapoval L Age related medication for addiction treatment (MAT) use for opioid use disorder among Medicaid-insured patients in New York. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0215-4

9. Cicero TJ, Surrat H, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Relationship between therapeutic use and abuse of opioid analgesics in rural, suburban, and urban locations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(8):827-840. doi: 10.1002/pds.1452.

10. Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Research network involvement and addiction treatment center staff: counselor attitudes toward buprenorphine. Am J Addict. 2007;16(5):365-371. doi:10.1080/10550490701525418

11. Zaller ND, Bazazi, AR, Velazquez L, Rich JD. Attitudes toward methadone among out-of-treatment minority injection drug users: implications for health disparities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(2):787-797. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020787

12. Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: a systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016;35(1):22-35. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960

13. Bell J, Strang J. Medication treatment of opioid use disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87(1):82-88. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.06.020

14. Boyer EW. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):146-155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202561

15. Lloyd J. The clinical use of naloxone. FDA website. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. www.fda.gov/media/92994/download

16. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment;Rettig RA, Yarmolinsky A, eds. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment executive summary. National Academies Press (US); 1995. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232111

17. Medications to treat opioid use disorder. National Institute on Drug Abuse website. Updated June 2018. Accessed October 8, 2020. drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/medications-to-treat-opioid-addiction/overview

18. Oesterle TS, Thusius NJ, Rummans TA, Gold MS. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid-use disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-2086. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.029

19. Park TW, Friedmann PD. Medications for addiction treatment: an opportunity for prescribing clinicians to facilitate remission from alcohol and opioid use disorders. R I Med J. 2014;97(10):20-24.

20. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families. Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series, No. 63.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018. Accessed Jan25, 2020. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535268

21. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. 2015. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Published 2015. Accessed October 8, 2020. store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma15-4907.pdf

22. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1419-1427. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1

23. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(no RR-1):1-49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464

24. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;8(3):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209

25. Kelty E, Joyce D, Hulse G. A retrospective cohort study of mortality rates in patients with an opioid use disorder treated with implant naltrexone, oral methadone or sublingual buprenorphine. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(3):285-291. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1545131

26. Rich KM, Bia J, Altice FL, Feinberg J. Integrated models of care for individuals with opioid use disorder: how do we prevent HIV and HCV? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(3):266-275. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0396-x

27. Medication and counseling treatment. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Accessed October 8, 2020. samhsa.gov/medicationassisted-treatment/medications-counseling-related-conditions

28. Moran G, Knudsen H, Snyder C. Psychosocial supports in medication-assisted treatment: recent evidence and current practice. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation website. Published July 8, 2019. Accessed October 8, 2020. aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/psychosocial-supports-medication-assistedtreatment-recent-evidence-and-current-practice

29. Opioid treatment programs and related federal regulations. Congressional Research Service website. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed October 8 2020. fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10219.pdf

30. Practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. The American Psychiatric Association website. Accessed October 8, 2020. psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615371969

31. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. The American Psychiatric Association website. Published 2006. Accessed Jan 25, 2020. psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/substanceuse.pdf

32. Flavin L, Malowney M, Patel NA, et al. Availability of buprenorphine treatment in the 10 states with the highest drug overdose death rates in the United States. J Psychiatr Pract. 2020;26(1):17-22. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000437

33. Are you in recovery from alcohol or drug problems? know your rights: rights for individuals on medication-assisted treatment. US Department of Health & Human Services website. Published 2009. Accessed October 8, 2020. atforum.com/documents/Know_Your_Rights_Brochure_0110.pdf