- Center on Health Equity & Access

- Clinical

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Insurance

- Policy

- Technology

- Value-Based Care

A Window Into Lyme Disease Using Private Claims Data

Claims data are used to track rising incidence of Lyme disease and its relationship to autoimmune disease.

Lyme disease is becoming an increasingly widespread and serious public health concern. According to the CDC reported cases rose markedly from 1995 to 2015, and approximately 300,000 people are diagnosed with Lyme disease each year in the United States. To advance the state of knowledge about Lyme disease, we delved into FAIR Health’s database of over 23 billion private healthcare claims. We found evidence of how the disease is affecting the nation’s rural and urban areas differently, how different age cohorts are impacted, where it is spreading and how it correlates with autoimmune disease.

The Rural/Urban Divide

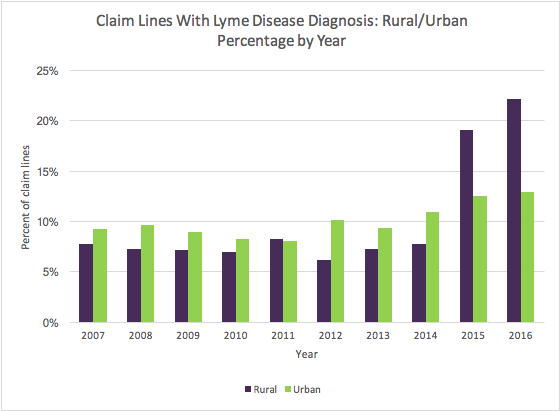

Caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted to humans through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks primarily in wooded and brushy areas with high grass, Lyme disease, not surprisingly, has been growing faster in rural than urban settings. Looking at private insurance claim lines (the individual procedures or services listed on an insurance claim), we found that in rural areas, claim lines with a Lyme disease diagnosis increased 185% from 2007 to 2016. In urban areas in the same period, there was also an increase, but smaller: 40%. Of those urban diagnoses, it is not known how many result from an infection in an urban park or yard and how many result from a rural infection—say, a holiday in the country—that is diagnosed only when the patient returns home to the city and visits a local provider.

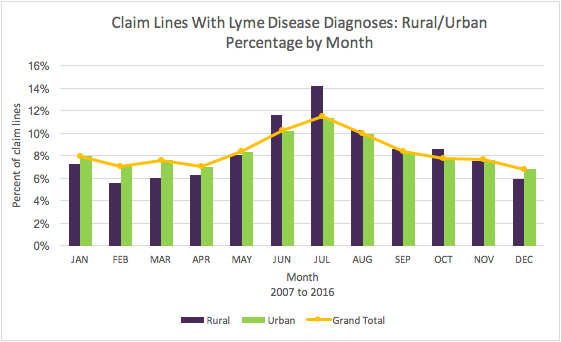

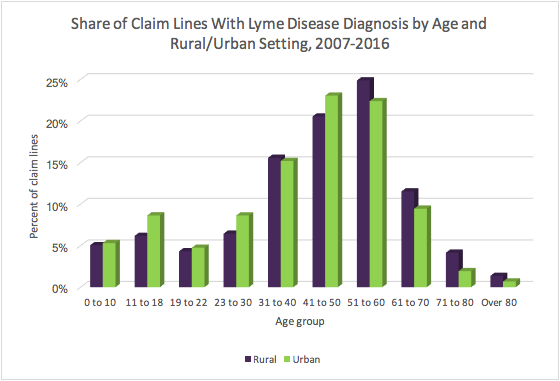

“Percent of claim lines” in the charts below is the percent of all claim lines associated with a given diagnosis (eg., Lyme disease) in a given time period (eg., 2007-2016).

Not surprisingly, summer is the peak season for Lyme disease. Our data for the period 2007-2016 show claim lines with a Lyme disease diagnosis overall were highest in June, July and August. Rural and urban settings differed, however. In June and July, claim lines with Lyme disease diagnoses were more common in rural than urban settings. But in the winter and early spring months (December, January, February, March and April), claim lines with Lyme disease diagnoses occurred more often in urban than rural settings. However, it should be recognized that the location where the service represented in the claim line was rendered may differ from the location where the infection was transmitted.

The prevalent age cohorts whose claim lines had diagnoses of Lyme disease in the period 2007-2016 also differed in rural and urban settings. In rural settings, claim lines for middle-aged and older people diagnosed with Lyme disease were more prevalent: people aged 41 years and above accounted for 62% of the rural claim lines with the Lyme disease diagnosis. But, in urban populations, younger individuals were represented by a larger share of such claim lines.

The Spread of Lyme Disease

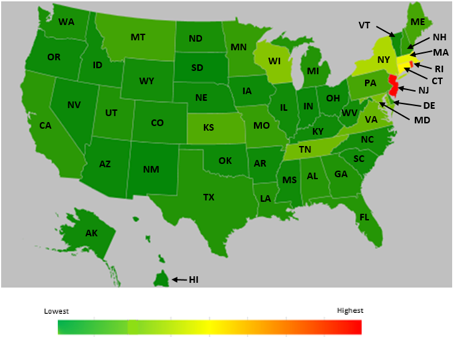

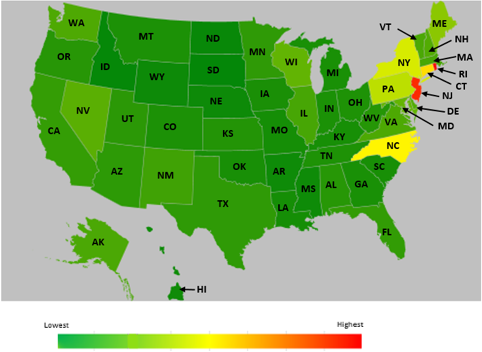

Although Lyme disease historically has been concentrated in the Northeast and upper Midwest, our data suggest that it is spreading. In the United States in 2007 (as shown in the heat map below), claim lines with Lyme disease diagnoses as a percentage of all claim lines with all diagnoses in the state were highest in the Northeast. The states with the highest percentages of such claim lines were (in order from highest to lowest) New Jersey, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York.

Nine years later, in 2016 (as shown in the heat map below), the 5 states with the highest percentage of claim lines with Lyme disease diagnoses as a percentage of all claim lines with all diagnoses in the state were (in order from highest to lowest) Rhode Island, New Jersey, Connecticut, North Carolina and New York. It appears that the disease had found a foothold in the South. The states that had the fewest claim lines with diagnoses of Lyme disease compared to all claim lines with all diagnoses in the state were (in order from lowest to highest) South Dakota, Idaho, North Dakota, Wyoming and Nebraska.

Lyme Disease and Later Associated Diagnoses

Typical early symptoms of Lyme disease, which is treatable with antibiotics, include fever, fatigue and headache. If allowed to go untreated, the infection can affect joints, the nervous system and the heart. Even if treated, some patients develop a longer-term illness, post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS), sometimes called chronic Lyme disease, with symptoms such as fatigue, joint and muscle pain and cognitive issues. The cause of such lingering symptoms remains poorly understood, but some researchers believe that they may result from an autoimmune reaction to the infection.

To investigate the relationship of Lyme disease to other diagnoses, we performed a retrospective longitudinal study, examining private insurance claims from a statistically significant cohort of individuals from 2013 to 2017. Having identified the individuals in this population who were diagnosed with Lyme disease, we looked for the diagnoses that most commonly followed the Lyme disease diagnosis. The most prevalent diagnoses were joint pain (eg, dorsalgia, low back pain, hip and knee pain), general symptoms of chronic fatigue and other fatigue, soft tissue disorders (eg, myalgia, neuralgia, fibromyalgia, limb pain, pain in hands and fingers) and hypothyroidism. Notably, all were diagnoses that often have an autoimmune component.

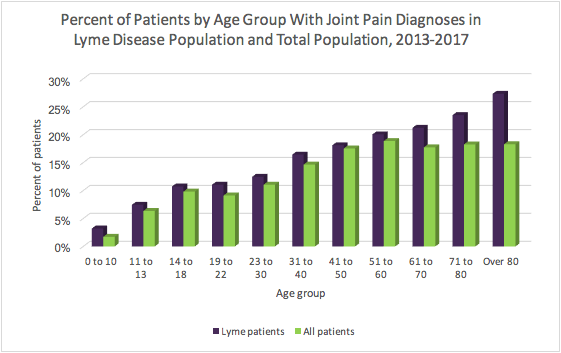

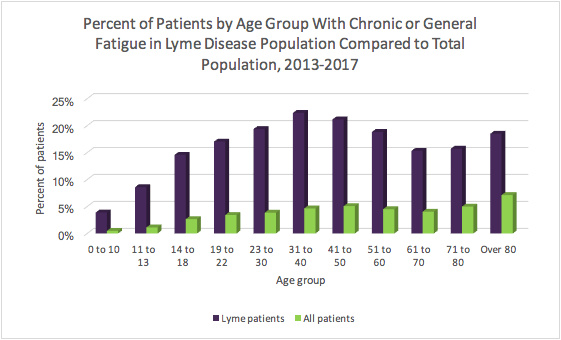

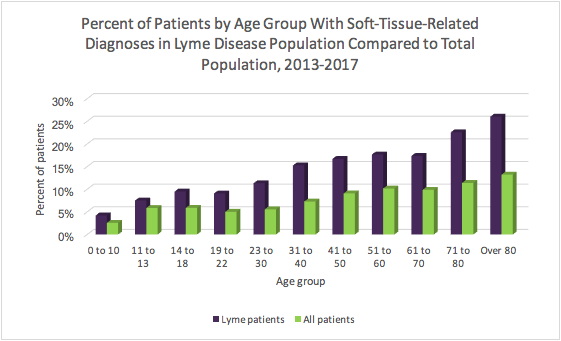

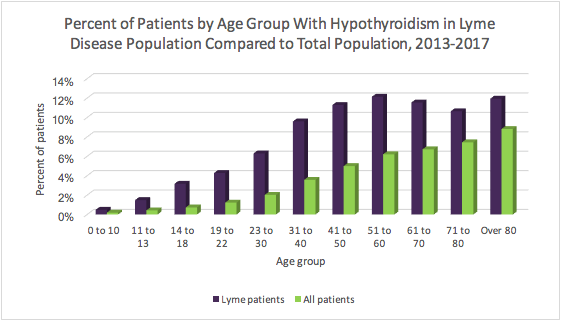

We then compared the distribution of these apparently related diagnoses by age in the Lyme disease population (“Lyme patients” in the charts below) to the distribution in the overall cohort (“All patients”). We found that, across age groups, patients with Lyme disease were generally more likely to develop these diagnoses than all patients.

For example, consider the total population of patients diagnosed with Lyme disease who had joint pain as a percentage of all Lyme patients. Compare that to the total population of patients with a diagnosis of joint pain as a percentage of all patients. In all age groups, patients with Lyme disease had a higher prevalence of joint pain.

The contrast was even greater with respect to chronic or general fatigue. Individuals diagnosed with Lyme disease were much more likely to have chronic or general fatigue after their diagnoses than the total population. In the 31-to-40-year-old age group, 22% of the Lyme disease population were diagnosed with chronic or general fatigue compared to 5% of the total population in that age group.

Soft tissue disorders, such as myalgia, neuralgia and fibromyalgia, were heavily diagnosed in the Lyme disease population compared to the total population as well. Even in children age 18 and younger, there was a 3% to 4% difference in the incidence of soft tissue disorders between the Lyme disease population and the total population, a gap that became much larger in older age groups.

Hypothyroidism, which is frequently caused by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune disease, was also much more prevalent in the population with Lyme disease than in the total population. There was a consistent 3% to 6% difference in the diagnosis patterns in most of the age groups.

Our data suggest that at least some autoimmune diagnoses correlate with Lyme disease. We hope our findings—about the rural/urban divide, the spread of Lyme disease and the diagnoses that frequently follow it—will be of value to researchers, policy makers and other healthcare stakeholders seeking to address this disease.

Telehealth Intervention by Pharmacists Collaboratively Enhances Hypertension Management and Outcomes

January 7th 2026Patient interaction and enhanced support with clinical pharmacists significantly improved pass rates for a measure of controlling blood pressure compared with usual care.

Read More